An ancient warlord’s stronghold on the Silk Road in Iran: archaeological project 1964-2010

Zardeh Tableland

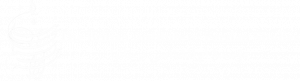

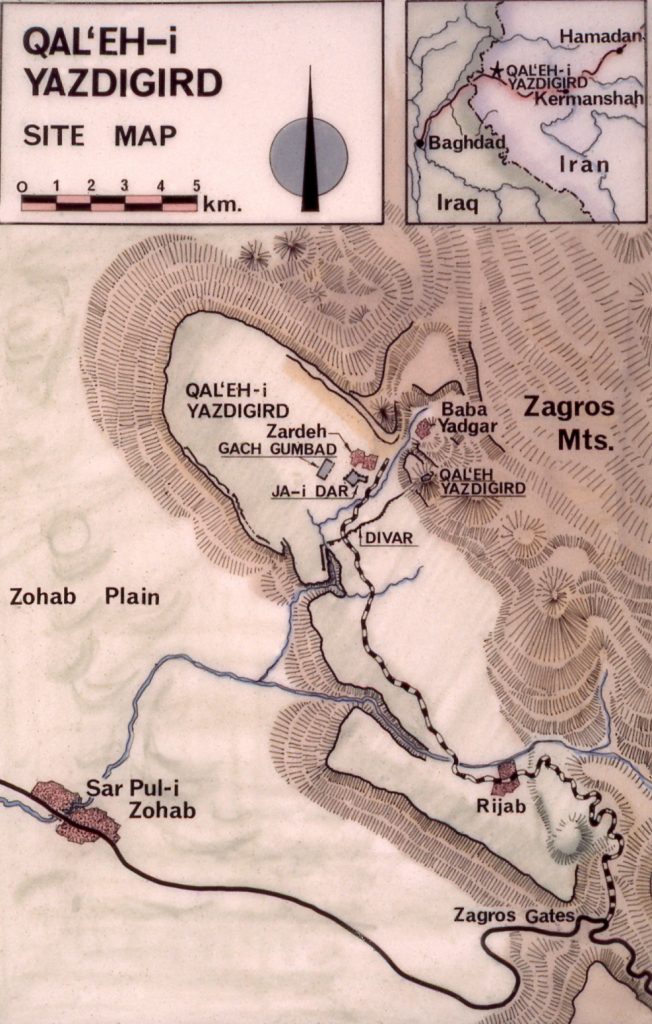

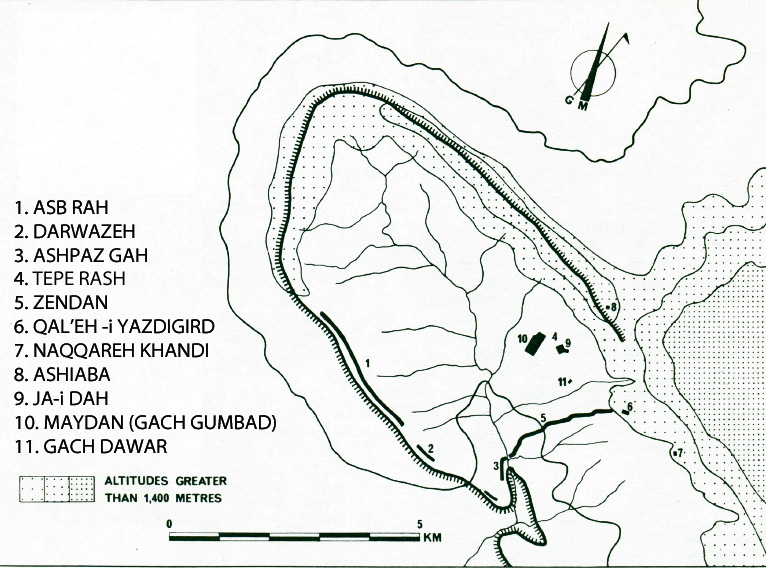

This archaeological site is defined by a thumb-shaped, basin-topped tableland measuring some 25 square kilometres in the Zagros mountains, on the extreme western edge of Iran. The old village of Bān Zardeh that nestles in the hollow of the basin allows us to refer to the area as the Zardeh tableland.

Centuries ago, elaborate steps were taken to add masonry walls to the already formidable, natural defensive quality of the escarpment and cliffs that delineate the tableland’s perimeter. A small fort on a pinnacle that overlooks the tableland from the upper ground above the cliffs to the east carries the legendary name of Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd ‘Yazdigird’s Castle’ – the castle of 7th century CE Sasanian King Yazdigird III.

This specific name has been applied for convenience in years past to define the archaeological remains of the entire Zardeh tableland, though technically the toponym applies only to the upper fort of an extensive stronghold of the 2nd century CE, most likely built by a Parthian warlord. Explanation for the site’s improbable association with 7th century Yazdigird III is to be found in the local Ahl Haqq religious beliefs and cultural practices which include a reverence for Iran’s pre-Islamic past. In the 3rd century CE, the government of Sasanian Iran that had deposed the Parthians, ended the era of the warlord, announcing their new strong authority by sponsoring a Zoroastrian fire-temple, a symbol of their state.

This Homepage is designed to introduce the reader to the overall nature of the archaeological project. It must be understood that comments presented here about traditional village life and land-use are based on observations that pre-date February 1979. No attempt is made to document the obvious heavy government investment in irrigation and road building in the area that can be seen in post-1980 satellite imagery.

Presented in pdf. format are published bibliographic entries relevant for understanding the site and interpreting its historical context. Also presented in the seven pages are the following subject themes, which include images.

Menu Tab 2: A History of the Qal‘eh-i Yazdigird Project 1964-2010

Menu Tab 3 : Climate, Land-use and Village Life

Menu Tab 4 : Standing Ruins and Trench Excavations

Menu Tab 5 : Stucco Architectural Decorations

Menu Tab 6 : Zoroastrian Fire-Temple

Menu Tab 7 : The Ahl Haqq (People of the Truth) and legends of King Yazdigird

Menu Tab 8 : Parthian and Sasanian Government

Early Explorations

The first writer to describe the archaeological remains of Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd was Major-General Henry Rawlinson. He led an expedition through the mountains of western Iran, as part of Britain’s attempt to bolster the border security of Iran (then called Persia) against potential encroachments by the Ottoman Turks and Russia. Besides being a high-ranking officer in the British India army, Henry Rawlinson was also a distinguished scholar of Middle Eastern history in his own right. His record of the British expeditionary force’s sojourn in the area of the Zardeh tableland presented in 1839 is the first western account of the ruins. Rawlinson’s record also includes an account of the beliefs of the Ahl Haqq. He accepted at face value the legends attributing the archaeological ruins to Sasanian King Yazdigird III.

In 1963, as a young British archaeologist, this writer – Edward Keall – was trying to build up a picture for himself of what Iran was like under Sasanian rule, beyond the glamour of the famous kings and their well-extolled exploits. I heard from a fellow student at the British Institute of Persian Studies about the remarkable ruins that he had seen while visiting the tomb of Bābā Yādgār. His description of a long defensive wall, traditionally associated with Sasanian Yazdigird III, was very intriguing (though ultimately misleading). A Sasanian connection seemed plausible to me, especially because in those days it was hard to conceive that the then little-known Parthians could have built fortifications in Iran on such a scale. My proposed investigation of Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd was conceived as part of what was my attempt to define Sasanian material cultural identity.

My investigation of the ruins started with a ride on mule back from Rījāb in 1964, in the company of Mahmud Aram, of the Iranian Archaeological Authority. On the basis of that brief visit, I made the decision to ask the Iranian authorities for permission to survey the ruins the next year and to conduct strategic soundings in the hope of unearthing Sasanian potsherds.

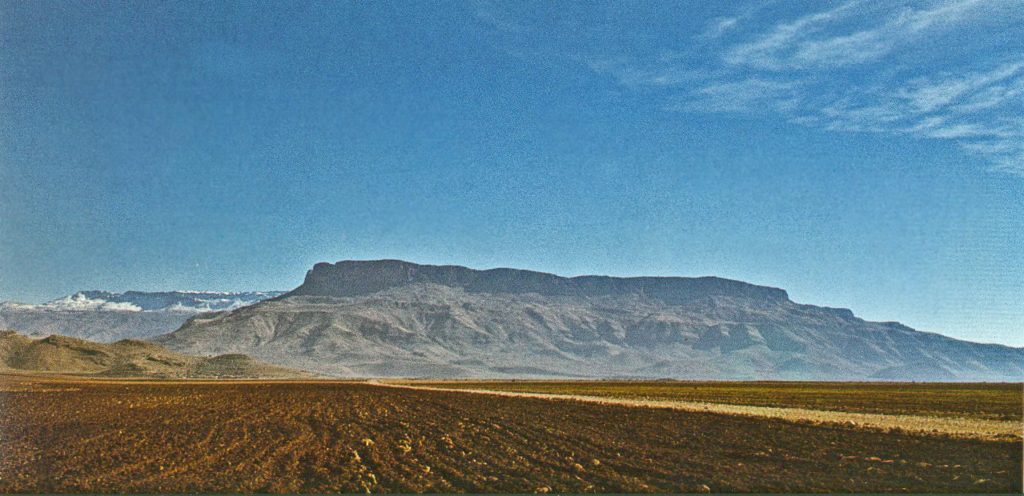

A basic principle of archaeological enquiry is that fragments of pottery made from fired clay (potsherds) do not disappear, even after the original vessel is broken and useless. Collecting potsherds and defining their typology from a site of unknown age can help assign a date to the site’s occupation.

While mapping the ruins in 1965, I observed potsherds galore in a ploughed field in the area locally called Tepe Rash. But, in digging a trench there, none were found below ground that could have provided the useful clues that I sought. Sensing my frustration, workers hired from the village of Bān Zardeh volunteered the idea that there were tangible remains to be found in the field of Gach Gumbad.

The words ‘Gach Gumbad’ in Persian mean literally ‘Plaster Dome’. I had fantasies that there was a memory of an ancient building with a plastered dome. Far from it. The toponym was derived from the fact that the villagers knew they could dig in the field to unearth lumps of gypsum plaster, for re-smelting when they needed to re-furbish the plastered dome of Bābā Yādgār’s tomb.

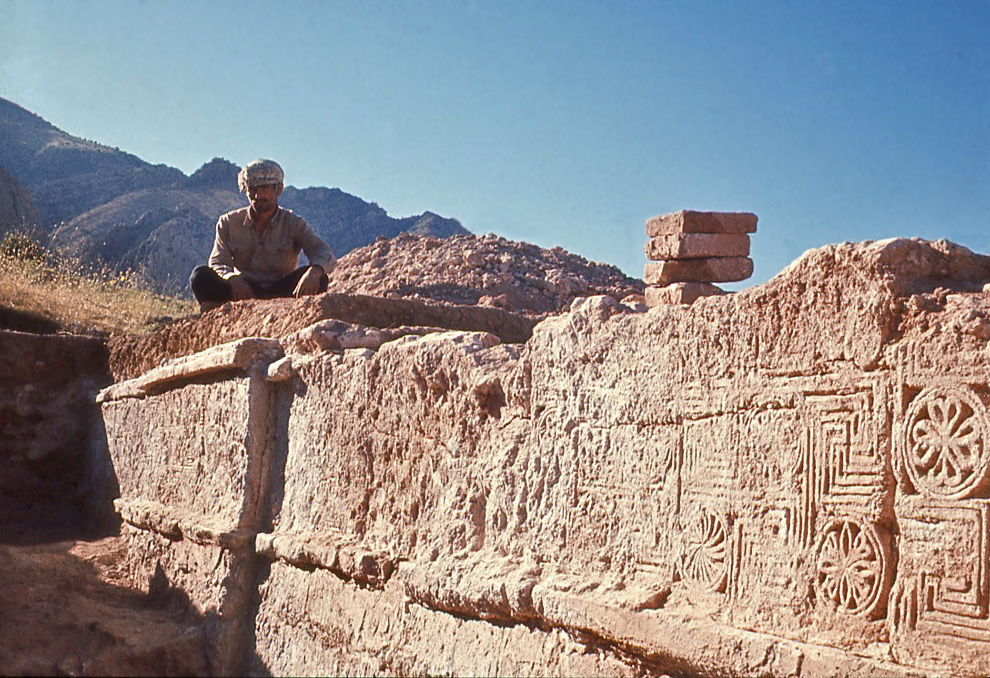

Digging at Gach Gumbad was initially as equally frustrating as in Tepe Rash fields, because there were masses of baked brick wall remnants still standing below ground, but no signs of any pottery. Making the decision to blitz down beside one wall in the quest for potsherds lower down, I reacted with total surprise, blurting out something like “My god, the wall is decorated with plaster ornament!” Alongside the wall we unearthed large pieces of architectural stucco decoration that had fallen down into the room from higher up, probably from somewhere just below the ceiling.

In the space of a week, we unearthed and registered 48 eclectic pieces of architectural ornament. Some of the figural designs had a strong sense of Sasanian art. Others had a much more ancient feel. This I attributed to the architect using ‘archaising’ elements (that is, a deliberate use of older designs from the Parthian era). The association of Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd with the Sasanian king of that name did not seem plausible, given the reality of Yazdigird III’s reign. But I was drawn to the description by medieval Arab geographers of a palace in the area built by the famous Sasanian King Bahrām Gūr, and mused about the idea of it being reflected in ‘Yazdigird’s Castle’. As a result, in 1967, I published a potential 5th century CE date for the Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd ruins.

Canadian Expeditions 1975-79

Ten years later, I was able to revisit the site, leading a Canadian archaeological team from the Royal Ontario Museum. Due to the work of the 1975 and 1976 seasons, the Sasanian picture began to disintegrate. Rather than reflecting archaic designs, the architectural decorations could increasingly be judged as genuinely of Parthian age. Those elements with a strong Sasanian feel could now be seen as ‘futuristic’ (that is, anticipating later Sasanian art styles). The main challenge now became how to explain the existence of a lavishly ornamented palace set within an impregnable stronghold in the Parthian era. The area has few significant natural resources of its own to generate the kind of wealth necessary to sponsor such a stronghold.

Late Parthian government was often weak and fragmented, its state territory shrinking in extent. But potentially there were riches to be gleaned from caravans that carried goods along the famous Silk Road as they approached the ‘Zagros Gates’ pass, just a short distance from the Zardeh tableland. Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd could now be interpreted theoretically as the stronghold of an unknown Parthian warlord who dominated this important ancient caravan route. Secure from attack by the Parthian King of Kings, the warlord could enjoy a lavish lifestyle so long as he could maintain an independent position,

In 1978, the Canadian expedition expanded the quest to learn more about the lifestyle of the Parthian warlord, beyond the phenomenon of his richly ornamented palace. But unexpectedly, when stones were cleared from one of the fields to complete construction of the dig-house facilities – the Sasanians suddenly came back into the picture. For the pile of stones turned out to be on top of the remnant of a once domed Zoroastrian fire-temple. This was a classic feature of the Sasanian era when Zoroastrianism was adopted as the state symbol of the new state.

The notion that the fire-temple was sponsored by the Sasanians can be reinforced by the fact that when they seized power in Iran from the Parthians in the early 3rd century CE, they established a much firmer state authority. Construction of the fire-temple can be seen as an official declaration that the era of the independent Parthian warlord was now over.

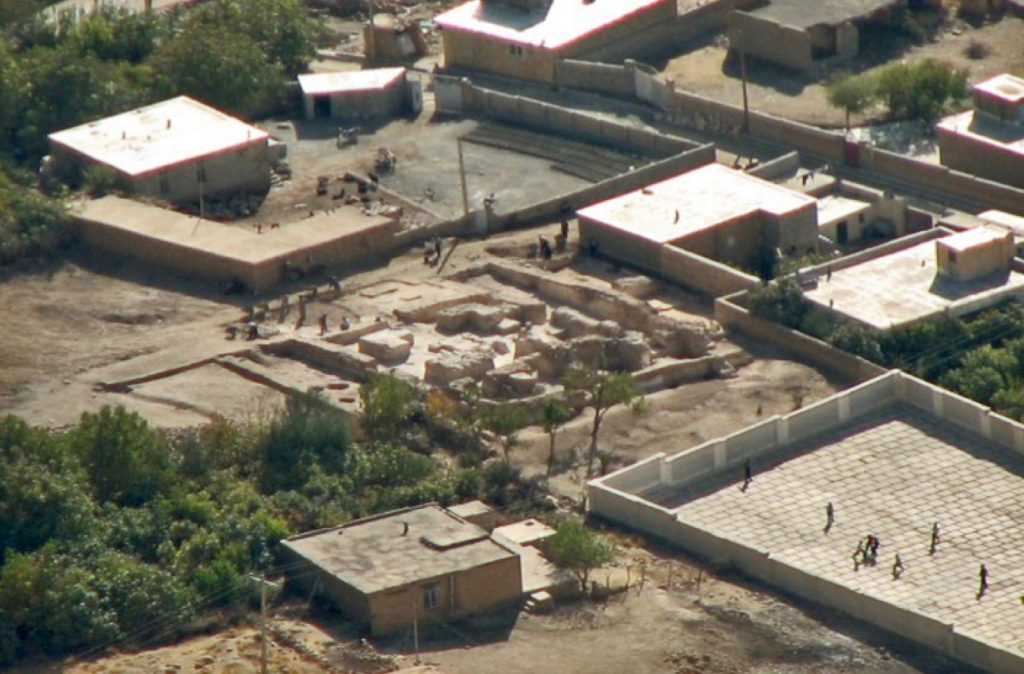

Iranian Heritage Organization Operations 2007-2010

In 2007 The Iranian Heritage Organization funded an operation, directed by Yousef Moradi, to explore and restore heritage sites between the Rijab and the Zardeh tableland. Part of that project was aimed at learning more about the Parthian era palace of Gach Gumbad, including some stabilization of the buried walls as they were exposed. The program was also directed towards halting potential damage to the fire-temple site (Gach Dāwar), due to encroachment upon it by the growing new village of Bān Gomeh.

For further reading see:

Complete bibliographic record by author name(s): 1839-2019

Acknowledgements:

Innumerable people from different backgrounds and walks of life played various roles in support of the project described in this website. The Canadian team included staff members of the Royal Ontario Museum, university students completing study project assignments, paid professionals, and volunteers. In addition, workmen were hired from the village of Ban Zardeh. None are named individually here, but all played invaluable roles.

Abrupt and enforced termination of the project in 1979 was a sad blow. Putting this website together has been a pleasurable reminder of the fantastic landscape of the archaeological site of Qaleh-i Yazdigird, and the warmth and colour of its contemporary inhabitants.

The project was sponsored variously between 1964 and 2010 by the British Institute of Persian Studies, the Royal Ontario Museum, the University of Toronto, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and the Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization (Kermanshah Branch). Thanks also to the Persian Dutch Network for media coverage and interview.

This website was compiled by Edward Keall and Susan Cantan (Royal Ontario Museum) with the technical assistance of Stanley Klassen (NMC, University of Toronto)