Qal‘eh-i Yazdigird: the question of its date

As outlined in the Project Overview (Link #1), the archaeological remains on the Zardeh tableland were originally designated as Sasanian in date in 1839 by the distinguished antiquarian Major Henry Rawlinson. His interpretation was largely based on accepting explicitly the local legends concerning the ruins which attributed them as the work of 7th century CE King Yazdigird III, the last of the Sasanian ‘kings of kings’. In my own initial study of the site I was heavily influenced by Rawlinson’s authority. In 1964 I was an archaeological student in Iran studying the Sasanians, and a Sasanian date for the ruins seemed most plausible. Nevertheless, even then I doubted that Yazdigird himself could have had the time to erect such elaborate defenses during the time of his hurried retreat before the advancing Arab forces of Islam.

Following a trial excavation in 1965, I still supported a Sasanian date, but suggested as more plausible, the time of 5th century CE Bahrām Gūr who is renowned for extensive construction activities in Iran. Design features in the decorative stuccoes that had a Parthian (i.e. pre-Sasanian) essence to them were explained away as being ‘archaising’ elements in the decorative scheme. At that time, in 1960s Iran, the Parthians were little known, and monumental architecture of the kind being documented at the site of Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd was unprecedented. As a result of the new archaeological program beginning in 1975, it became increasingly apparent that a Parthian date was in fact appropriate. Stuccoes excavated in the 1930s at Seleucia-on-the-Tigris were the best clue for this late Parthian date. It was concluded that the style of the palatial stucco artwork suggested a date probably somewhere around the 2nd century CE. So how to explain the historical context and motivation for sponsorship of this massive stronghold?

With regards to the overall life span of the archaeological ruins, most of the structural building techniques recorded on the site, as well as the pottery recovered from area of the military fortifications, also point to a Parthian date for original sponsorship of the stronghold of the Zardeh tableland. It is clear that operation of the stronghold as it had been originally conceived was terminated abruptly by the Sasanians in the 3rd century CE, along with construction of a Zoroastrian fire-temple, a state symbol of the new regime. There was considerable activity in the area in early Islamic times, including a major remodeling of the Upper Castle of Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd, likely under the Umayyads. There was considerable investment activity in Būyid times (10-11th century), but it is the Parthian period that leaves us with the most impressive remains.

Despite the impressive fortifications however, their scale makes them inappropriate for having been a military outpost of the 2nd century CE Parthian state. The decorations of the palatial pavilion are too lavish to justify them as having been part of a state-sponsored military complex – the region itself has few natural resources to support anything but a subsistence rural economy; also, the central government of Parthia was too weak at that time for us to envisage a royal hunting retreat on the Iranian mountainside. For, the reality of the Parthian monarch being distanced this far from the capital would inevitably have prompted his removal from the throne. It is clear that the government of late Parthia lacked both the resources and the opportunities to promote such programs.

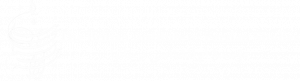

We can get some sense of the faltering of a monolithic Parthian empire (if ever such a thing existed) through considering the revolt of the Greek-speaking residents in Seleucia-on-the-Tigris between 35-42 CE. The revolt is regarded as an attempt to regain some of the political ground that was being lost to the Aramaic-speaking peoples of Babylonia, and to the Parthian nobility. The structure of imperial Parthia was in fact being torn apart. Between the time of Artabanus III (10–c. 38 CE) and Volagases I (c. 50-76 CE) the area controlled directly by the King of Kings shrank considerably. Parthia had increasingly to deal with Roman aspirations to establish influence in the East.

Sources for Parthian history

Our concrete knowledge of the late Parthian era is very poor, to say the least. The majority of textual references for compiling the historical record that can easily accessed were actually written by outsiders, often with a hostile attitude towards the Parthian state. The bulk of these accounts were written by authors representing the position of Rome, Parthia’s arch enemy. Such histories written by the Parthians themselves that may have existed, were mostly obliterated when the Islamic authorities declared the age before Islam to be that of the Jahalīyyah ‘Age of Ignorance’ and its records should not be preserved. There are historical commentaries using translations and summaries that try to reconstruct Parthian history written in Islamic times, but the details are quite minimal. The original sources for these accounts no longer exist.

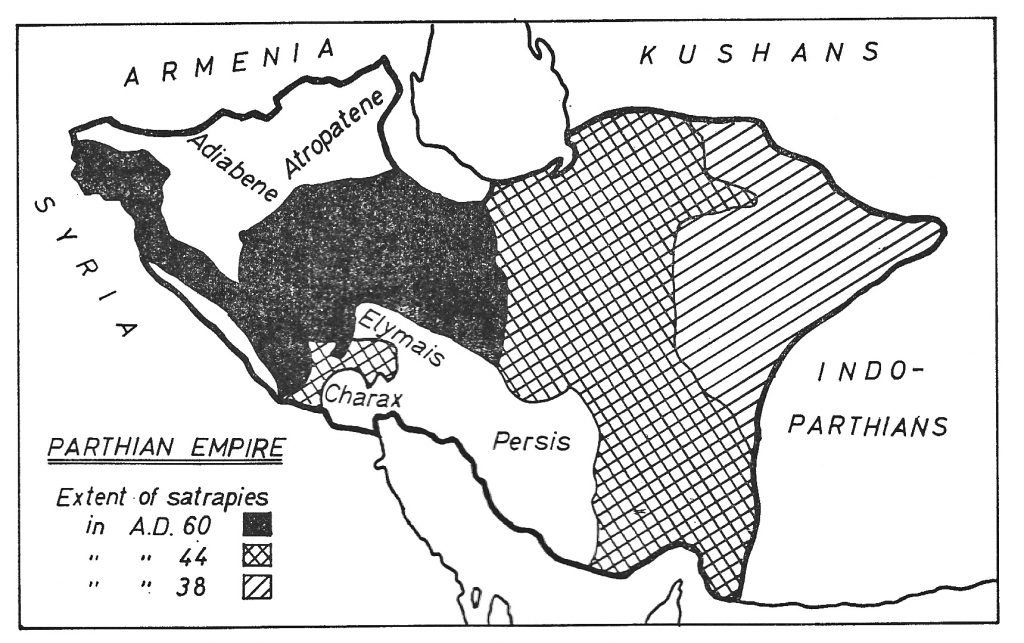

Hard core facts that we have on hand to establish a historical chronology are heavily dependent upon analyzing the coins that were issued by the Parthian state – comprising both the royal coins minted from silver, and the individual city issues minted in bronze. The primary royal coins consisted of silver tetradrachms that were theoretically four times the value of a drachm. The different patterns of circulation of these two coin denominations tell us something about the structure of the state – drachms circulated primarily on the Iranian plateau; and their inscriptions in Greek lettering became increasingly indecipherable.

The first monarch to expand substantially a Parthian state in Iran did so at the expense of Seleucid suzerainty over that territory. Around 155 BCE, Mithradates I forcibly occupied the region of Media in western Iran (centred on the ancient city of Ecbatana/modern Hamadan). Then, in 141 BCE he captured the old Macedonian capital of Seleucia-on-the-Tigris in Mesopotamia. At this point we may legitimately define the Parthian state as that of an ‘empire’, which Mithradates ruled until 132 BCE.

On coins struck by the royal mint, Mithradates bore the simple honorific title of Basileōs Arsākou ‘King Arsaces’. It was he who began the practice of having the Parthian king simply called ‘Arsacid’ – that is, he traced his royal inheritance back to Arsaces, the legendary founder of the Parthian state of the mid-3rd century BCE. A subsequent successor to Mithradates, Mithradates II (ruled 124/3-88/7 BCE), expanded Parthian territory considerably. But he faced serious security problems in the form of secessionist movements on both the eastern and southern fringes of the empire. Nonetheless – and perhaps in fact because of it – Mithradates claimed the title of Basileōs Megalou Arsākou ‘Great King Arsaces’.

One may legitimately argue that Mithradates adopted the new title as a standard protocol formula, part of a program devised to re-claim authority in the territories that the Achaemenids had once held in their powerful prime. One may reasonably argue also, that this significant change in title protocol, was being coined literally as a propagandistic way of enhancing the image of what in reality was a monarch facing difficulty in keeping the expanded Parthian empire intact. There are plenty of modern analogies where state rulers – such as the ‘Supreme Leader’ of North Korea – are tempted to adopt this kind of approach, to better their image in the eyes of the people.

There are some sporadic examples of how Mithradates II even actually occasionally used the old Achaemenid title of Basileōs Basileōn (“King of Kings”), as did some of his immediate successors. But it was Orodes II who adopted it consistently after around 57 BCE, whereafter it became the standard Parthian formula. Along with the new title came permanent use of the term Philhellene (“Friend of the Greeks”) – a conciliatory gesture to buy the political support of the Macedonian Greek settlers in Mesopotamia. The term had originally been coined by Mithradates after his capture of the old capital of Seleucia-on-the-Tigris in 141 BCE, but it was not used consistently until the time of Orodes II (ruled ca. 57-38 BCE).

When the tetradrachms bear the year-dates of their minting they do so according to the Seleucid calendar. This provides us with the era’s irrefutable basic chronology and identification of the individual kings. For the purposes of this account of Yazdigird’s Seraglio we can usefully represent that, around the mid-1st century CE, the Parthian kings started to identify themselves on their coins with their personal names. Previously they had only represented themselves with distinctive portraits, their individual headgear, and honorific titles. It was king Gotarzes who standardized use of a personal name in 50/51 CE. Small bronze coins, mostly of civic issue, also bear a year date of issue. This helps in identifying the relationship between urban centres and the Parthian monarch.

Curiously, in the year 389 SE (CE 77/78) two kings minted tetradrachms with identical fabric and inscriptional formulae – except for the two kings’ names (Pacorus and Volagases). From the fact that both claimed the title ‘king of kings’ one can plausibly argue that they were both contenders for the throne, able to buy the relatively independent services of the royal mint in Seleucia which would strike tetradrachms on demand. Certainly it is most likely that the use of this grand title now meant little more than ‘king’. As indicated earlier, original adoption of the more grandiose title appears to have been connected with the perceived need to strengthen the image of a weakened monarchy.

On the other hand, of course, one might argue that although perhaps there was some kind of rivalry between the two, it was not necessarily overt civil war, but at least some kind of power sharing arrangement. However, the subsequent coin issues suggest the former explanation. Although Vologases II seems to have dropped out of the running, a third figure (Artabanus IV) appeared on the scene briefly also claiming the ‘king of kings’ title. But eventually Pacorus emerged as the stronger figure, adopting imagery on his coins that were deliberately chosen to reflect his claim to authority. This includes a victory coin where he is depicted on horseback (393 SE = CE 81/82); and in 404 SE (= CE 92/93) he adopted a tiara headgear as a sign of grand authority.

But the scenario of the struggles for the throne in the first century CE sets the stage for the next century when there was no strong centralized control of the Parthian empire. Supporting this observation is the reality that the two denominations of royal coins – drachms and tetradrachms – circulated in different areas of the Parthian realms. The tetradrachm was the medium of the Mesopotamian reaches of Parthian Iran, while the drachm circulated exclusively on the Iranian plateau. In addition, the bunched hairstyle on the drachms of 2nd century CE king Osroes has a decidedly Sasanian look; the frontal portrait of king Vonones II is also totally in keeping with an ‘Iranian’ style rather than a Greek one.

Compatible with this principle is the evidence that around CE 150 a drachm was struck in Iran – in Media, its northwestern region – that has no personal king’s name associated with it, only the generic title formula of ‘King of Kings’. Numismatists have labeled this type of drachm as the coin of the ‘Unknown King’. The coin reflects the fact that Parthian empire was extremely fragmented at this time, and regional lords held enormous amounts of local power because of the weakness of the central government. A coin of this type was once found by a farmer in the fields of the Zardeh tableland. It seems to mesh very well with the idea of regional autonomy, even independence.

To my mind, the most plausible explanation for the extraordinary fortress of Serā-y Zard Yazdigīrdī and its ornately decorated palace (known through the published record as Qal‘eh-i Yazdigird) is that it was the work of a late Parthian warlord. Strictly speaking, this means that this figure was a dissident. Without other obvious natural resources from the area to furnish funds to build this lavish stronghold, it is judged that the capital needed to construct it and maintain it most likely came from tariffs levied on merchant caravans for safe passage through the nearby narrows of the ‘Zagros Gates’ mountain pass. Using the term ‘warlord’ implies that the actions reflected in the use of the stronghold represents activity outside of the purview of the central government of Parthia. I have even used in the past the term ‘robber baron’ in an attempt to define the character of the stronghold’s sponsor. To be sure, this may reflect too much a sense of dissidence, and perhaps one should be open to the idea that a degree of autonomy for a local lord, and freedom to control the highway for his own purposes, was tolerated by the Parthian so-called ‘King of Kings’. The ‘Tāq-i Gīrrāh’ pass carries traffic between Tehran and Baghdad still today. Its ease of passage has made it the most logical way to move between the lowlands of Mesopotamia (to-day’s Iraq) and the Iranian plateau. But that also made it vulnerable to tight control.

Control of the caravan traffic along the ‘Great Asian Highway’

The hey-day of caravan traffic along this particular route occurred in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, and the artwork of the decorated palace of Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd is compatible with this date. It is apparent now, as a result of excavations that began in 1978 and were re-activated in 2007, that the extravagant lifestyle of the Parthian warlord was snuffed out in the early 3rd century CE by the Sasanians when they seized power in Iran. The Sasanians adopted Zoroastrianism as a new state religion. It is argued here that construction of a fire-temple in the area of Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd served as a symbol of the new government regime. Details of the excavations are presented in Link #5.

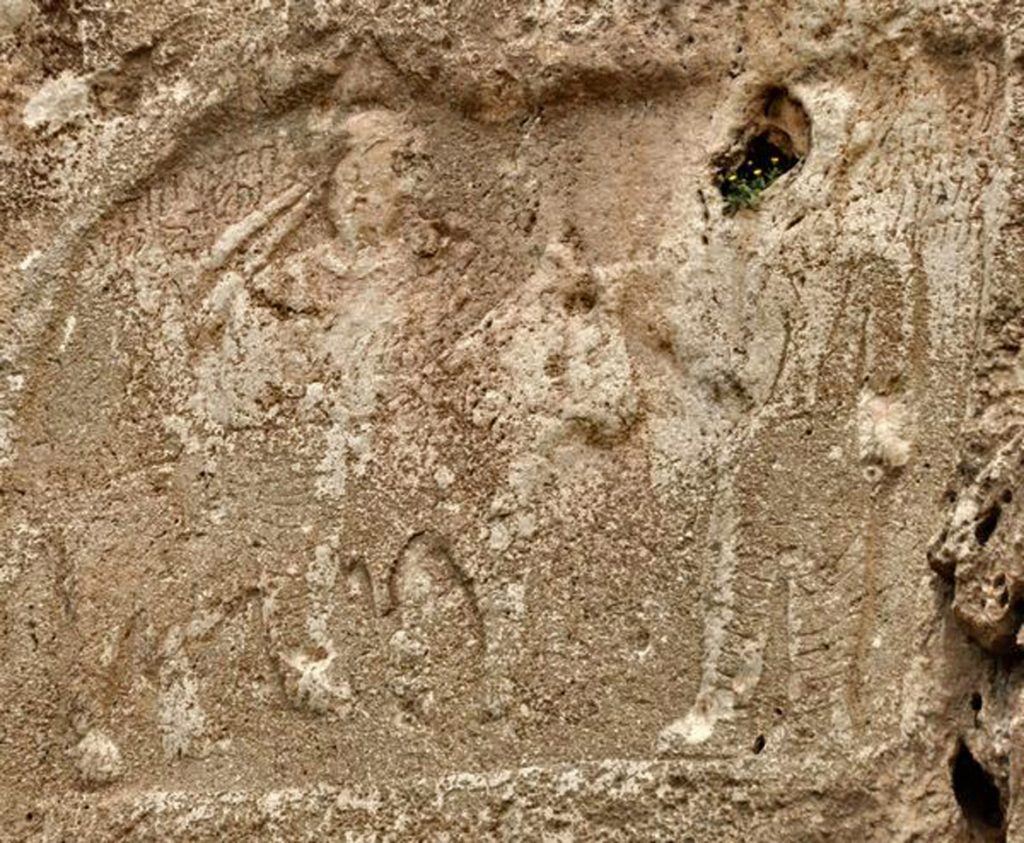

There are different ways to evaluate these hypothetical conclusions. On the one hand one can emphasize the ‘rebel warlord’ character of the stronghold’s proprietor. In this vein I myself have even spoken in terms of a ‘robber baron’. But there is equally room to support another argument, based on the interpretation of a severely eroded Parthian rock relief carved on a rock-face outside of the modern town of Sar Pūl-i Zohāb (medieval Hulwān) – immediately below the fortified tableland of Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd.

The rock relief depicts a scene where a man on a horse greets a standing figure whose arm is raised towards the rider. The horse-rider wears a diadem which automatically assigns him a position of authority, even that of the Iranian concept of divinely-assigned ‘kingship’. Above the horse-rider is an inscription in Parthian Aramaic that describes it as ‘the image of Goudarz, king’. To my mind, it is highly significant that the horse-rider does not claim the title of ‘king of kings’, the standard title used by the late Parthian monarchs. So it is more plausible to think of the horse-rider as a ‘king’ of a district recognised by the central authorities as either truly independent as a ‘kingdom’, or more plausibly as autonomous, as a ‘vice regent’ of a district. If the latter case can be supported, one could argue for the horse-ride to be the ruler of the district of Hulwān, ancient Chalonitis.

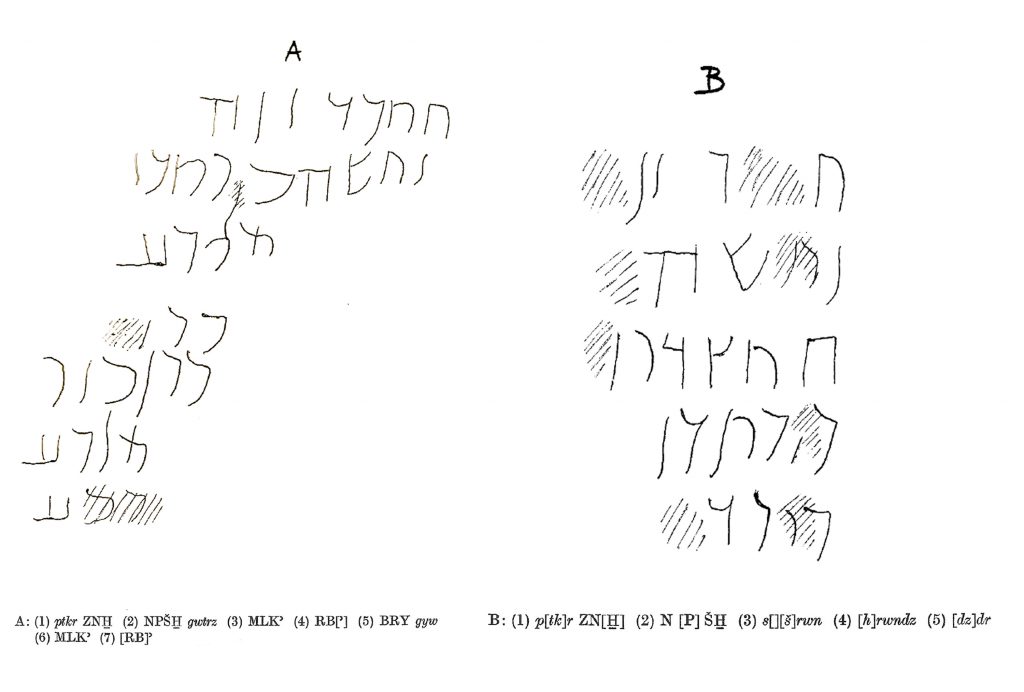

The inscription above the standing figure is unfortunately very eroded, and different commentators have read it differently. But the relationship between the two figures is clear, if one follows the standard interpretation of ancient Iranian rock-reliefs – the horse-rider is the dominant figure, the standing figure (arm raised) is in a position of receiving some kind of acknowledgement. The scene does not represent a position of submission, for in that case the subservient figure would be portrayed grovelling before the horse-rider. To my mind, the Sar Pul rock-relief may possibly depict the scene of the ruler of Hulwān district acknowledging the position of the lord of Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd, as a powerful figure controlling the mercantile caravan traffic through the Zagros Gates. The Parthian central government did not have the ability to defeat the Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd warlord, so it came to some kind of accommodation to deal with the reality, to the satisfaction of both sides. One can envisage that there was strong local support for the local warlord and it would not have been feasible to obliterate him, nor even a state priority to do so given all the other critical issues that the Parthian monarchs faced. Gropp’s (1968) transcription of the inscription interprets the standing figure ass[]šrwn [h]rwndz [dz]dr hulwan dyz ‘Keeper of the Fortress of Hulwān’.

Sasanian take-over of Iran

As a final note on the political state of late Parthian-early Sasanian Iran, there is a priceless chronicle written in the Middle Persian language (Pahlavī) – the Kārnāmagh-i Ardashīr – that narrates the struggles of the first Sasanian king (Ardashīr) to establish the new kingdom of Iran in the early 3rd century AD. From this we may extract some nuances about the administrative and social structure of Parthian Iran, and we may apply them in our attempt to reconstruct the history of Qaleh-i Yazdigird. Most significantly, the Kārnāmagh text describes Iran as controlled by two hundred lords (Khwadāy Khudā).

The Kārnāmagh text describes the 3rd century exploits of king Ardashīr – as he tried to reign in under his control the various maverick parties that had characterized the Parthian period. Other sources give us the colourful story of Ardashīr’s drawn out struggle to put down resistance by Haftān Būkht whose castle was protected by a friendly dragon (‘kīrm’). The castle was only taken when the protective dragon was poisoned through treachery. It is totally erroneous to link Haftān Būkht with Qal‘eh-i Yazdigird, as others have tried to do (see Izady 1993), for Haftān Būkht was based in Kīrman, not Kīrmanshah. But the analogy of a powerful local lord who strongly resisted the new Sasanian regime is totally appropriate.

For further reading see:

Keall 1975d; 1975c; 1977c; 1994; 2019