Zoroastrian Fire-Temple

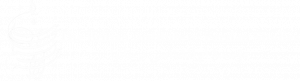

As described in the Homepage and Links #1 and #3, the discovery of a Sasanian fire-temple on the Zardeh tableland was through a completely unexpected chance encounter. The project began in 1978 as an operation to collect fieldstones for use in completing construction of the ROM expedition compound walls. Stones had been piled up in a huge heap in a field, in order to clear the ground around for ploughing. The heap totally obscured the remnants of a monumental building whose four distinctive piers when exposed allowed the ruin to be characterized as a ‘chahār-tāq’ ‘four arches’. This made it theoretically identifiable as a classic Zoroastrian fire-temple. But the 1978 excavations were concentrated mainly on some ancillary rooms adjoining the chahār-tāq on the northwestern side of one of the inner circumambulatory corridors. No work was done at that time in the interior of the chahār-tāq. The recovery of pottery dating to Abbasid times in very ashy contexts in the ancillary rooms led to the conclusion that they had been added on to the Sasanian fire-temple in Islamic times, being used as industrial work spaces. Subsequent excavations directed by Yousef Moradi, on behalf of the Iranian Heritage Cultural Organization, corrected this conclusion. The ancillary rooms had indeed been built as add-ons to the chahār-tāq and used in Islamic times. But their original construction did actually date to Sasanian times when the complex functioned as a fire-temple.

It was fortuitous that the real story behind the life of the fire-temple complex emerged in 2007. The reason for this was that the Kermanshah branch of the Iranian Heritage Cultural Organization was sponsoring a major ethnographic and archaeological study of the whole area between the Zardeh tableland and Tāq-i Gīrrāh, including heritage building conservation. The vale of Rijāb was an important component of the study. The program included re-opening and extending excavations initiated by Keall in the 1960s and 1970s. The fire-temple complex of Gach Dāwar was a major feature of the new work, particularly because modern building development was beginning to encroach upon the archaeological site. This construction activity had been facilitated by the fact that the surrounding fields were bulldozed flat by the Iranian army in 1979. This was done to accommodate a military camp set up as part of defensive measures taken to withstand Saddam Hussein’s attempted invasion of Iran, by way of the Zagros Gates, during the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s. Luckily the fire-temple escaped serious damage. But after the war, the flat space offered inviting opportunities for the villagers of Bān Zardeh to build new spacious homes, with superior access to the road for vehicles.

As part of this program, the entire fire-temple complex of Gach Dāwar (formerly reported under the rubric of Kala Dāwar) has been excavated, and some of the original ROM observations proven to be wrong (as usually happens with continuing excavations). The Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization work of 2007 included excavation of the interior of the Gach Dāwar chahār-tāq structure, and exposing the podium of the central fire-altar.

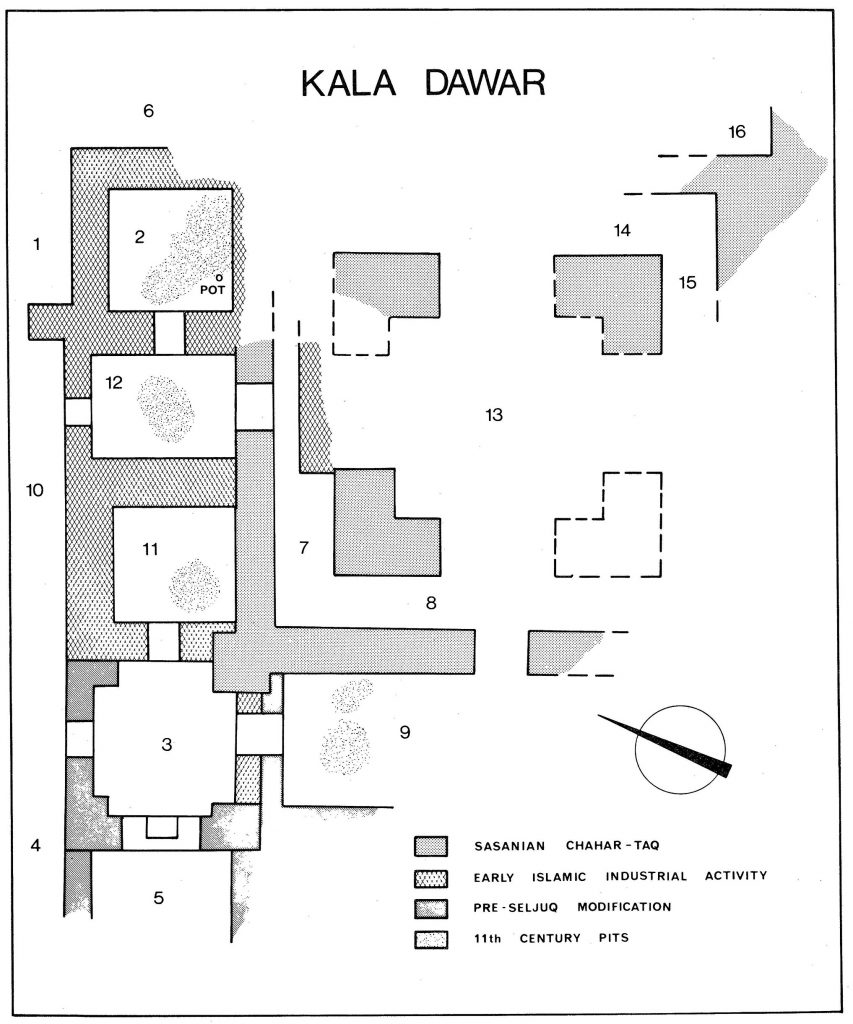

The Iranian team concluded that there had been two major phases in the construction of the temple, as well as numerous modifications – all within Sasanian times. The recovery of Abbasid pottery and a Buyid coin from the interior space of the fire-temple underlines the fact that the structure was still standing in early Islamic times.

The earliest phase was not excavated because it would have involved destruction of the remains of the later phase. The Iranian team clearly demonstrated that the structures of the ancillary rooms were actually an integral part of the fire-temple, albeit as additions to the original chahār-tāq. It is agreed that these rooms were re-used for non-religious purposes in Umayyad-Abbasid times, though the original hypothesis concerning use of the spaces for glass-making has not been substantiated.

The remains of the fire-temple

The chahār-tāq was constructed, and later re-built, employing a standard Iranian masonry composition involving both roughly dressed and undressed field stone embedded in a cemented pack of gypsum mortar. For the undressed masonry work, stones with a flattish face were selected to furnish the exterior surface of the wall, with an interior pack of smaller rubble cement masonry. Occasional vertical joints reflect the piecemeal masonry construction technique. A few recycled baked bricks were used in the masonry matrix. A top finishing coat of surface plaster was applied over a 10cm thick base-coat. Numerous layers of finishing plaster indicate that the structures experienced wall repairs after intervals of time. The original floors were substantially made, employing cobblestones embedded in a concrete screed set over a levelling layer of dirt and mortar. These floors were also laid piecemeal, the joints between each laid bed obscured by the overall floor surface finishing plaster.

The central space would have been roofed with a circular dome, carried by squinches in its zone of transition, in the standard Iranian manner. Circumambulatory corridors may have been barrel-vaulted in brick masonry, but possibly covered by mud that would have furnished a flat roof – based on the evidence of the unearthing of a flat-roof stone roller.

Building phases

The 2007 season of work identified five phases of construction activity and building use. The first one, which established a chahār-tāq on the site for the first time, actually involved two distinctively separated stages of construction. Phase IA was never exposed by the excavation team; rather, it was discernible only due to the fact that a cavity in the floor of the Phase IB chahār-tāq made it possible to peer through it and ascertain that there had been an earlier stage in the life of the fire-temple, seen by observable remains of cult installation features.

The lower stage remnants remain buried, due to the Heritage Organization’s decision not to obliterate the remains of the upper stage. The reason for the over-building of the first chahār-tāq was that erosion on the slopes of the adjacent hillside – likely due to largescale deforestation of the area in Parthian times – had precipitated the build-up of sediments against the outside, upslope wall of the fire-temple, making it virtually impossible to gain entry into the inside of the complex. To remedy the problem, gravelly back-fill was poured systematically into the interior of the chahār-tāq complex. This action buried the original structure, but its layout and cult features were duplicated at a higher level.

Built features and layout

Phase I

The layout of the chahār-tāq involved construction of four L-shaped piers, hence the terminology used here, together with circumambulatory corridors that help immediately define the complex as a Sasanian Zoroastrian fire-temple. In the heart of the complex, a raised platform provides unequivocal proof that the structure was designed as a fire-temple.

The raised central platform itself has small L-shaped piers built of baked brick at each of the four corners, suggestive of having once provided the supports for a protective canopy above the sacred fire. This central platform, with a plinth of three diminutive steps, is easily interpreted as a podium for carrying a fire-altar, though unfortunately the excavators found no traces of features of this kind. On one side of the platform, a deep trough was designed as a depository to house ashes produced through the burning of the sacred fire. On excavation, the presence of ashes in the trough beneath fallen masonry indicates that the fire-temple was still in operation at the time of its demise. Steps from the floor to the base level of the raised podium can hypothetically be seen as providing convenience of access to the altar by the officiating priest. There are masonry traces that indicate intermittent refurbishing of the liturgical structure.

Set on the southwest side of the complex, but built as part of the original building scheme of the fire-temple, was a long space (room #9) constructed at a lower level than that of the main temple, to accommodate the natural lower height of the terrain. Beyond that, and also part of the original building scheme of the fire-temple, were two rooms (#21; 22) that had no access into the heart of the fire-temple complex. But benches alongside one of their walls suggests a possible role for accommodating community traditional rituals, such as festival activities when foodstuffs were offered to commemorate the souls of the dead, or for liturgical recitations of Zoroastrian sacred texts.

Phase II

Major structural additions to the complex involved construction of three small ancillary rooms (#2; 12; 11) on the northwest side of the complex, furnishing entry into the heart of the complex from outside by way of a small eyvan room (#12) into one of the circumambulatory corridors (#7) of the fire-temple. These rooms were built using the same construction technique as those employed in the earlier phase of the fire-temple. Found in the excavations was a ceramic vase once embedded in the cobble concrete floor in room #2. It likely once contained something precious, and was found by treasure seekers in the Islamic era.

On the northeastern side a monumental entranceway space #19 was constructed, giving access into circumambulatory corridor (space #15) and facing onto a walled courtyard compound, with steps rising up to accommodate the natural slope of the terrain. Entranceway space #19 was furnished with two piers that likely carried a lintel, in the manner of the standard Iranian porches for which the descriptive word ‘tarma’ ‘columned portico’ can be applied. The entranceway hall eventually had additional piers set in its four corners, as well as free-standing features of unknown purpose built on the floor, one of which had traces of burning.

Also during Phase II, the eyvan of entrance space #12 was modified by reducing the open side of the hall to now house a doorway. Access from the entrance into the two flanking side-rooms (#2 & 11) was subsequently blocked. These spaces were then reached by entering them from the circumambulatory corridor (#7).

Phase III

This involved the addition of a fourth ancillary room at the western corner of the complex (#3). Originally there was an entranceway on one side from the outside, as well as a door that gave access to the interior of the complex. The shallow recesses on all four sides of the room give it a cruciform look. It is tempting to see this distinctive shape as indicating a special function, conceivably that of being a sanctuary to house the sacred fire. Subsequently, access from the outside was completely blocked off and a supporting bastion was added to the western corner of the main building.

Phase 1V

Modifications made to the northeastern side of the complex, involved the addition of a single long room (#16) and a small entrance hall to that space (#17) that looked out onto the walled courtyard. The long hall had passageways to both the interior of the complex, as well as to the outside. But the outside passages were eventually blocked off in Phase IV, to deal with the continuing problem of an upslope terrain surface constantly rising.

Phase V

This was moderately minor in scale, involving the blocking off of several doorways within the complex.

The Islamic era

In early Islamic times, large pits were dug through the plaster floors of each of the ancillary side rooms on the northwest side of the complex, likely by treasure seekers.

In one of the rooms, the robbers were successful. They found a glazed pottery jar that had originally been embedded in a rough envelope of plaster (seemingly as a way of preserving its contents) before being buried under the floor of the room, apparently for safe keeping. The pot itself had no value, and when the treasure-hunters found it they broke open one side and presumably removed its content, leaving the jar in its original burial spot. Before the results of the work of the Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization, it was concluded on the basis of its decorative style that the treasure-pot could be attributed to the Abbasid Islamic era. As a result of the new Iranian work it may be hypothesized that in fact the buried treasure-pot may actually be of Sasanian date, and connected with the life of the fire-temple. Conceivably there may have been in Umayyad times a living memory of the existence of this buried jar in one of the rooms of the fire-temple.

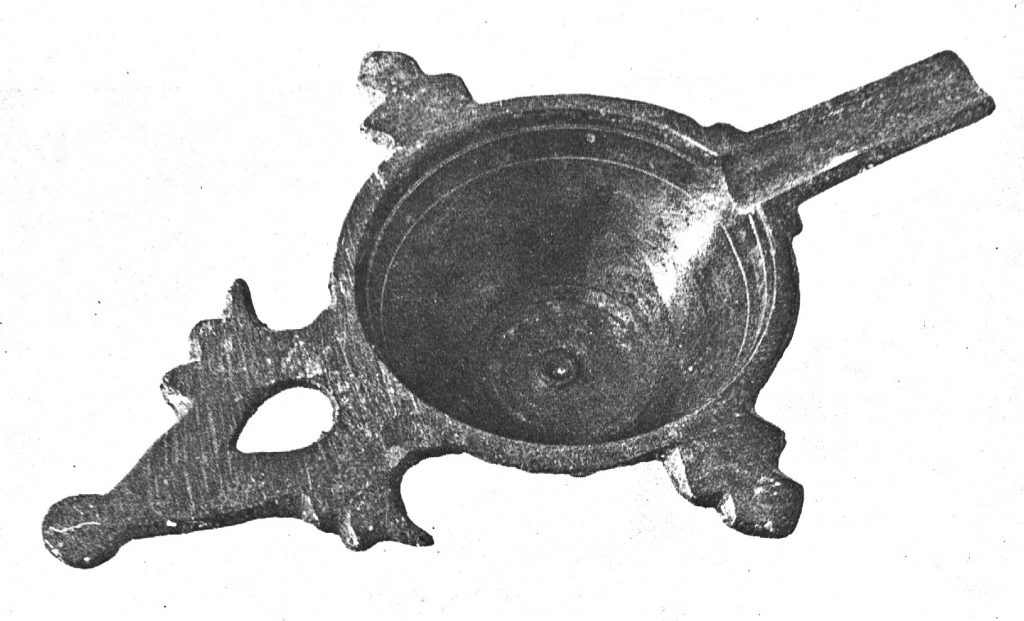

But one of the most remarkable of the discoveries made during the Iranian Heritage Organization season of excavations was that the fire-temple had continued to be used for Zoroastrian ritual purposes for centuries after the beginning of Islam. This revelation is based upon the fact that, up to the time of the final demise of the fire-temple complex through earthquake damage, ash from the sacred fire was still being deposited in the trough provided for it at the side of the fire-altar podium. Three Būyid era silver dirhems recovered from beneath the collapsed masonry – including two specifically minted in Baghdad during the rule of Sultān Shamsān al-Dawla (AH 373-75 = CE 984-986) – gives us the approximate date for when the fire-temple was still operating. A spouted bronze cup with handle recovered from the debris, once thought to be a lamp, is now judged to be a ‘kōhl’ make-up applicator instrument, typologically datable to the 10th -11th century CE.

As explained on the Homepage, while the excavation of the Gach Dāwar fire-temple site was being undertaken by the ROM Mission in 1978, most of the expedition’s attention was applied to the ancillary rooms (#2; 3;11;12) on the northwestern side of the complex. These spaces were clearly used in Islamic times (as late as the 11th century CE); of the artifacts recovered, a large number are represented by fragments of glass that were recovered from very ashy contexts. Ash-filled pits exposed in spaces #9 & #16 also suggest industrial activity of some kind in Islamic times, but this activity has neither been verified nor its nature determined. Whether the activity involved actual glass production, as once hypothesized, is a moot point. Virtually no traces of glass manufacturing, such as slag or wasters were recovered. It is also a moot point concerning what was the functional connection between these rooms in the fire-temple complex and the religious operation of the fire-temple itself (now that we know that the liturgical activities continued well into Islamic times). Were the glass objects somehow related to temple-related activity? Or was it completely unrelated activity? The numerous glass pieces recovered represent mostly fragments of small bowls and flasks.

For further reading see: