Traditional housing of Bān Zardeh

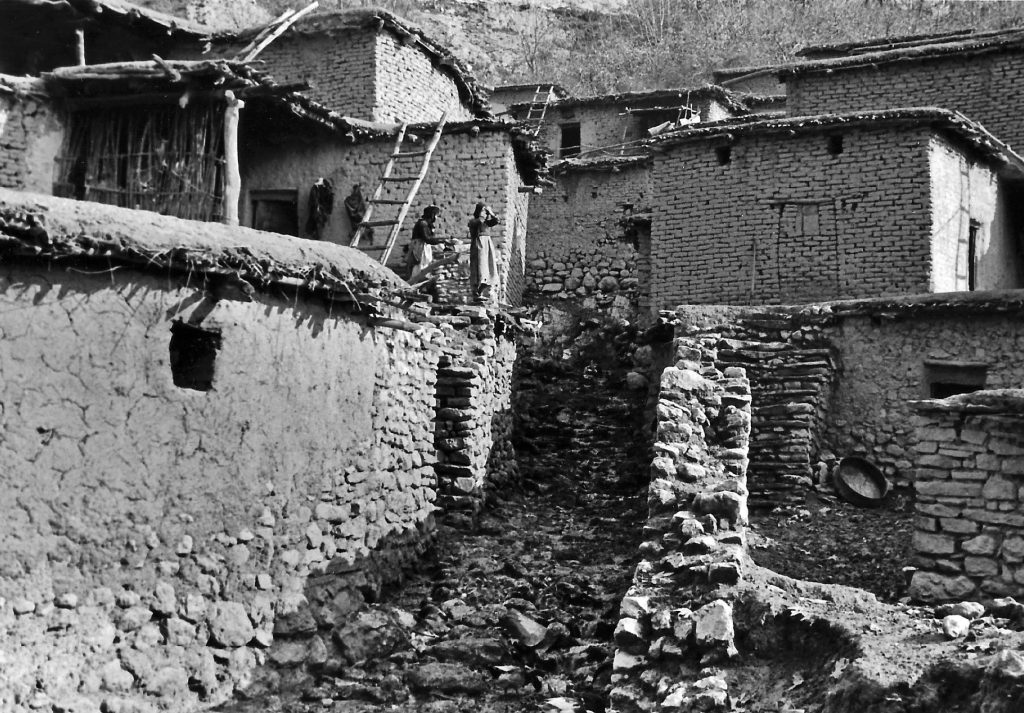

Until recently, the main village of the Zardeh tableland was built with homes and animal shelters constructed in a very traditional Kurdish way and using easily accessible local materials. The village of Bān Zardeh was a cluster of flat-roofed dwellings, nestled up against the slope of the mountainside. Many of the buildings were attached to one another; the roof-top of one building was often used as a work-area for the structure higher up the hill, acting like a forecourt terrace.

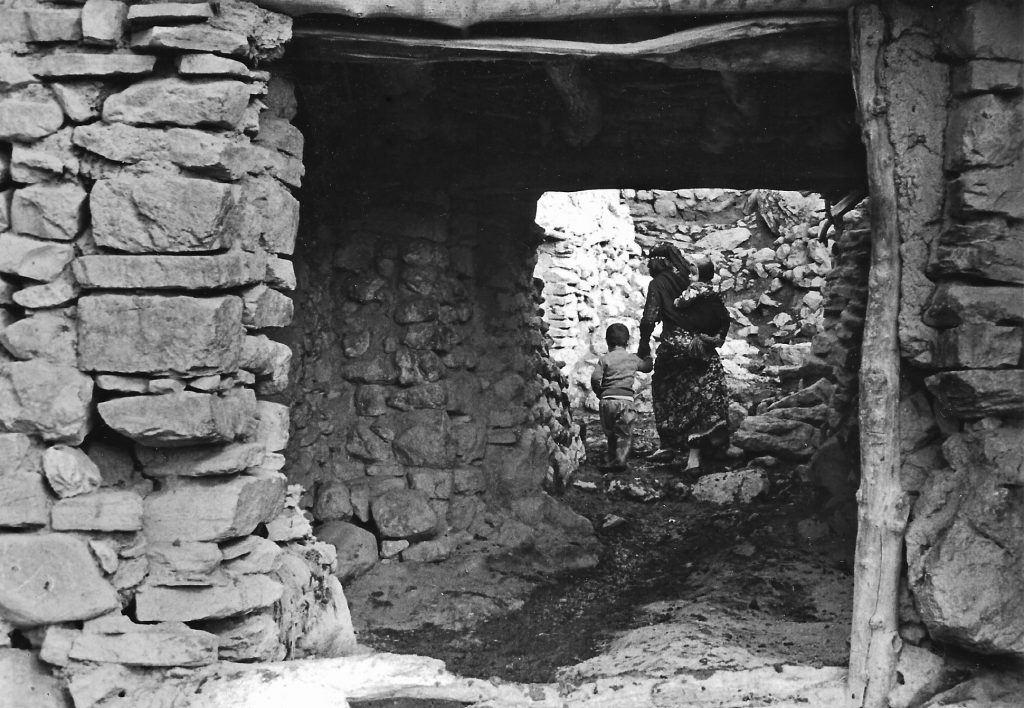

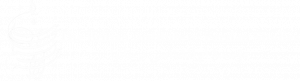

Part of each home was furnished with a place for safe storage of goods and shelter for animals overnight. Passage through the middle of the settlement was provided only by narrow pathways. Fierce guard-dogs protected each household.

4 & 5. Village alleyways.

To-day, the old village of Bān Zardeh is largely derelict, as seen in this satellite image taken in January 2014. Its residents re-located themselves to the modern village of Bān Gomeh where the ground offers more space for building, and better amenities.

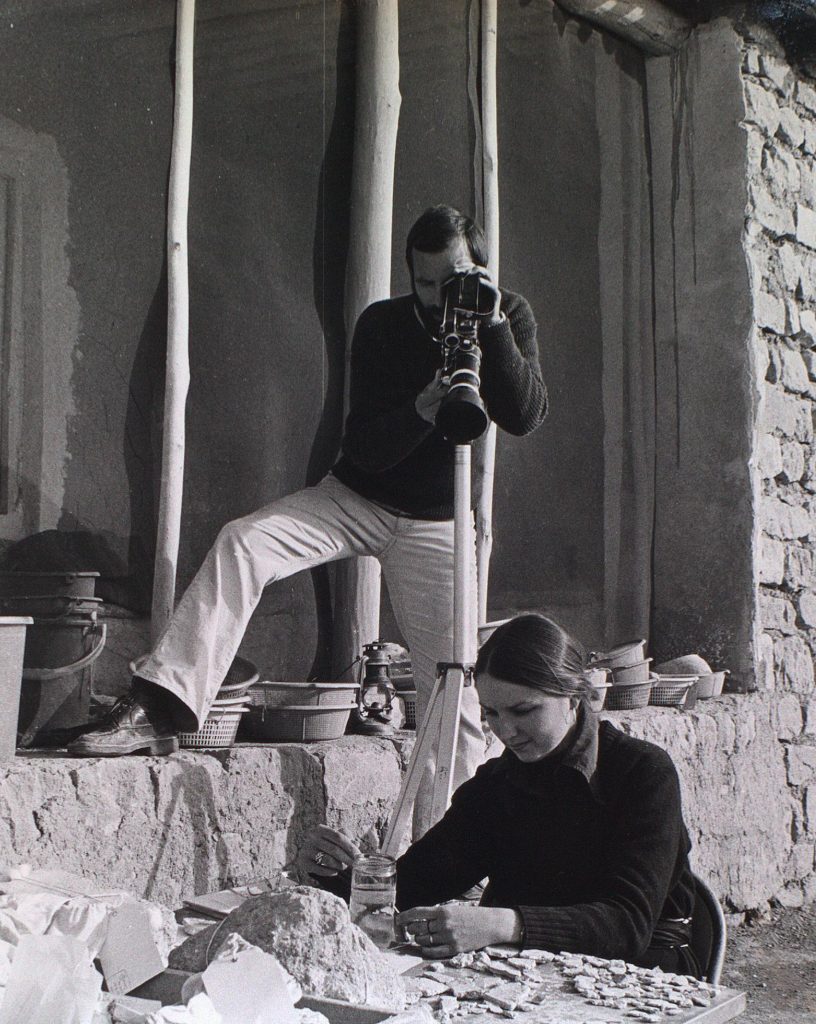

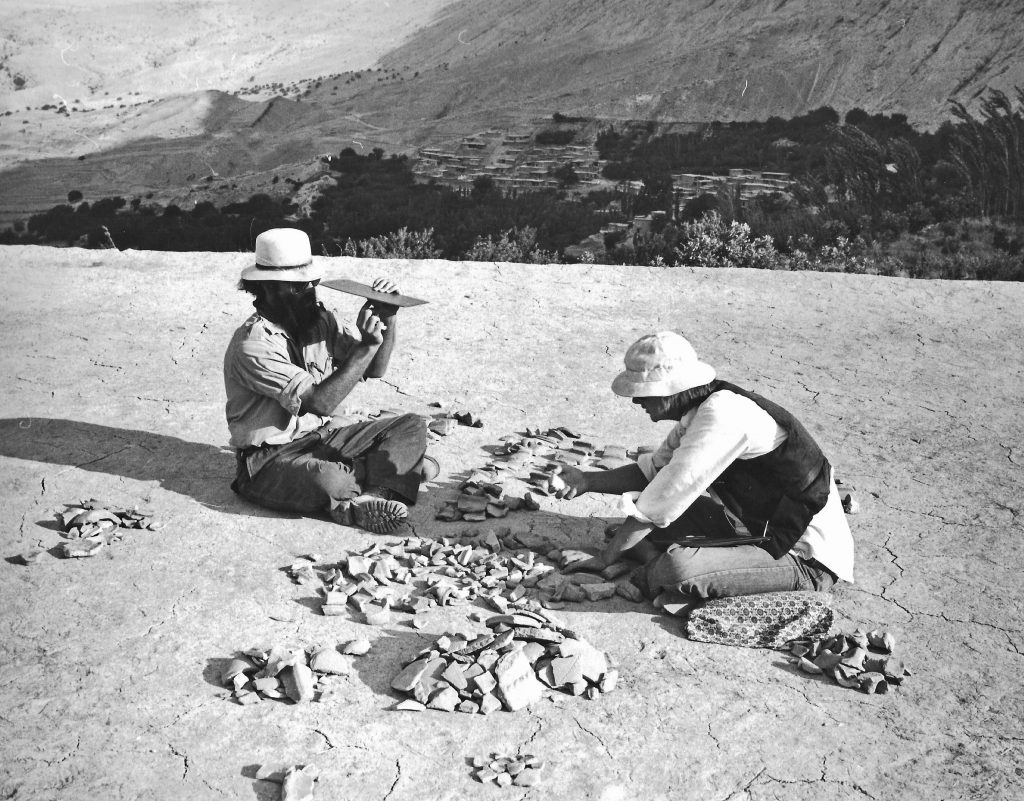

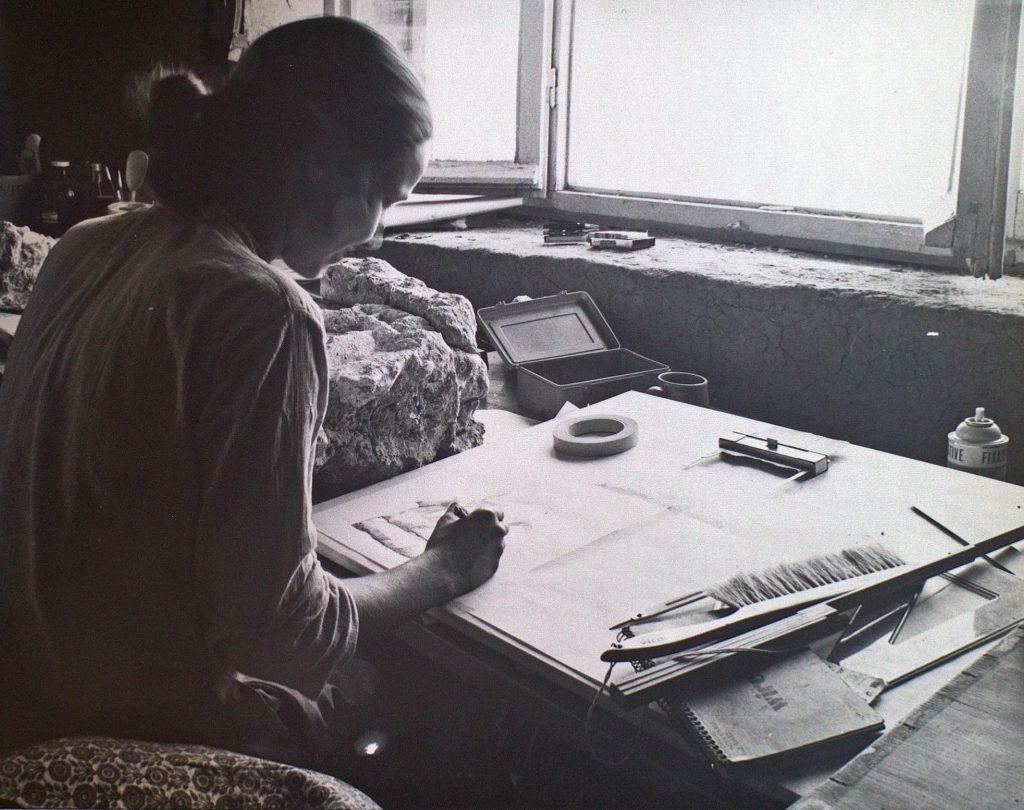

With the knowledge from the British archaeological operation of 1965 that there were massive walls covered in decorations buried below ground in the field of Gach Gumbad, a major Canadian program was launched in 1975 to develop the full potential of the site. In 1975, we were a team of six living in tents.

It was impossible to accommodate a foreign group of mixed team members in the village of Zardeh; there were no toilets in the village, and no privacy for personal bathing. Even the main artery was quite narrow; no space to manoeuvre a vehicle. It was also impractical to plan the cataloguing, recording and storage of hundreds of pieces of decorative artwork that the expedition could expect to unearth in the future. So the idea of building a dig house on land away from the densely settled village was born.

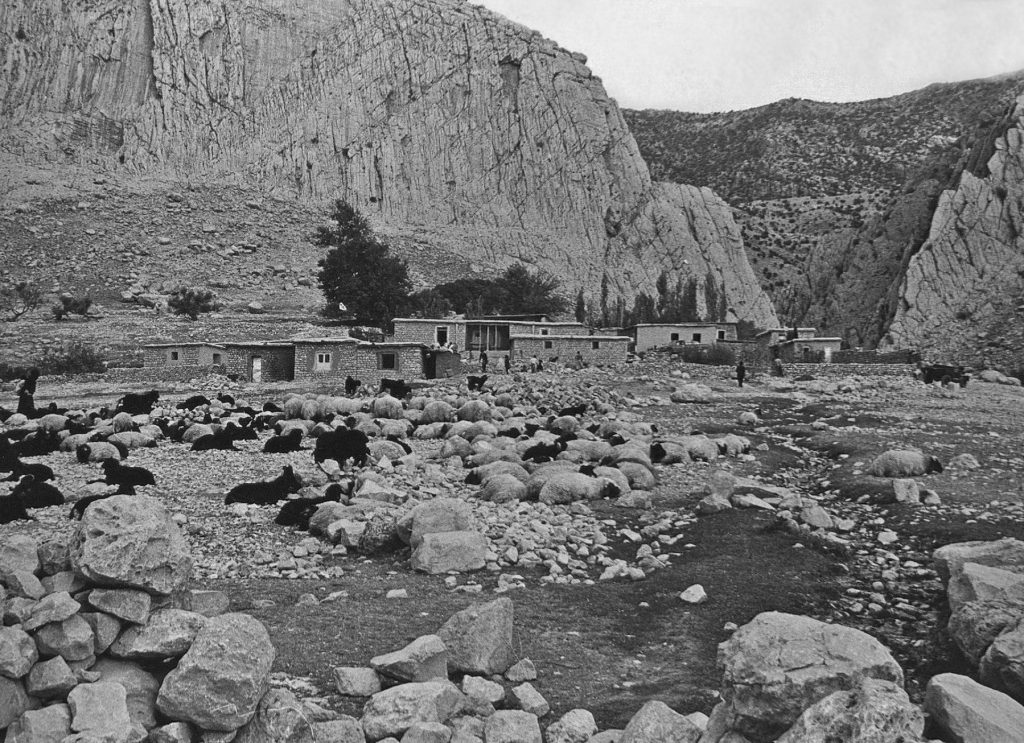

10 & 11. Main village artery and a herd of goats.

Building the ROM dig-house

The choice of a building plot was based on the fact that a local landowner – Dūst ‘Alī – was willing to sell a parcel of land on the open hillside, largely because the ground was mostly bare rock and devoid of soil suitable for farming of any kind. The proposed building site was adjacent to a track leading to the shrine of Bābā Yādgār which allowed for a motorized vehicle to reach the property easily. Most importantly, a branch of the Bābā Yādgār stream flowed through the property, providing the potential for all sorts of expedition purposes, especially washing artifacts and personal bathing.

The expedition house was built employing local labour, and utilizing the same materials and techniques that were used in building the traditional houses of Bān Zardeh. This meant room walls built of stones collected from hillsides, or boulders smashed with sledgehammers, and trimmed on one side using an adze to produce a roughly flat exterior face. Trimmed fieldstones were laid with uneven sides buried in a matrix of mud mortar.

13 & 14. Smashing boulders.

17 & 18. Laying stones to a face.

Second-hand wooden doors and windows were purchased in Kermanshah. Glass windows were a luxury. They were to help the expedition’s work; they were not normally used in the traditional village buildings of the area.

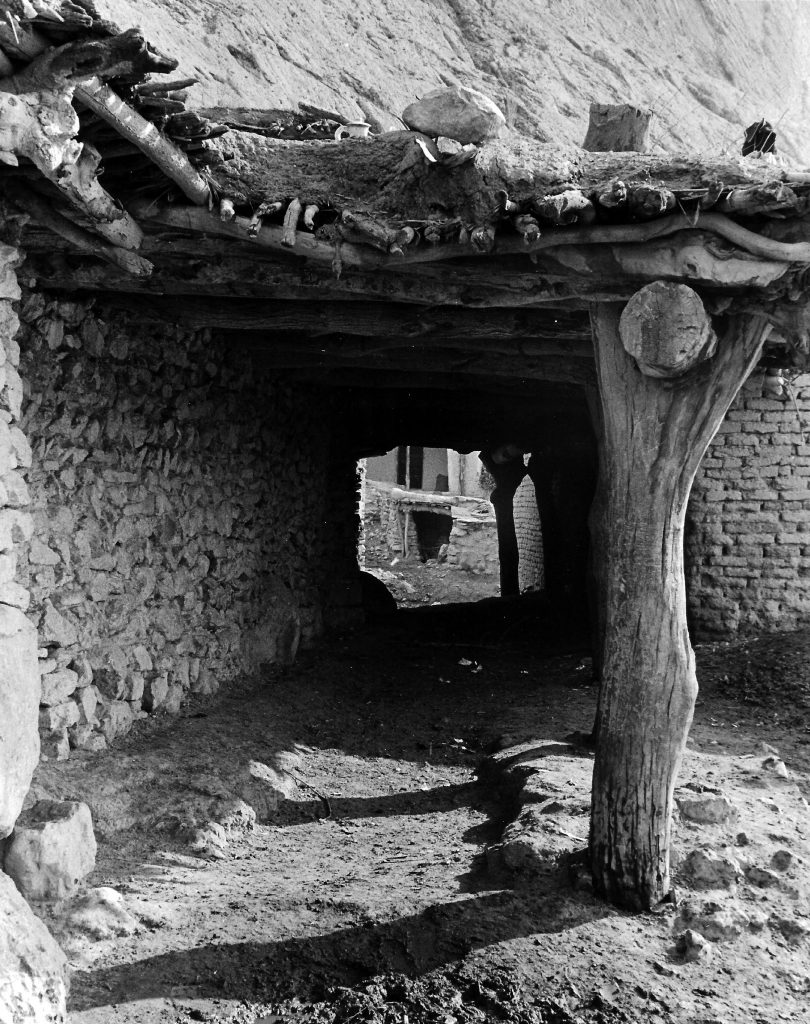

Debarked, but untrimmed tree-trunks of ‘chenār’ (sycamore) were used as wall toppings, and as posts and ceiling beams to carry a flat roof.

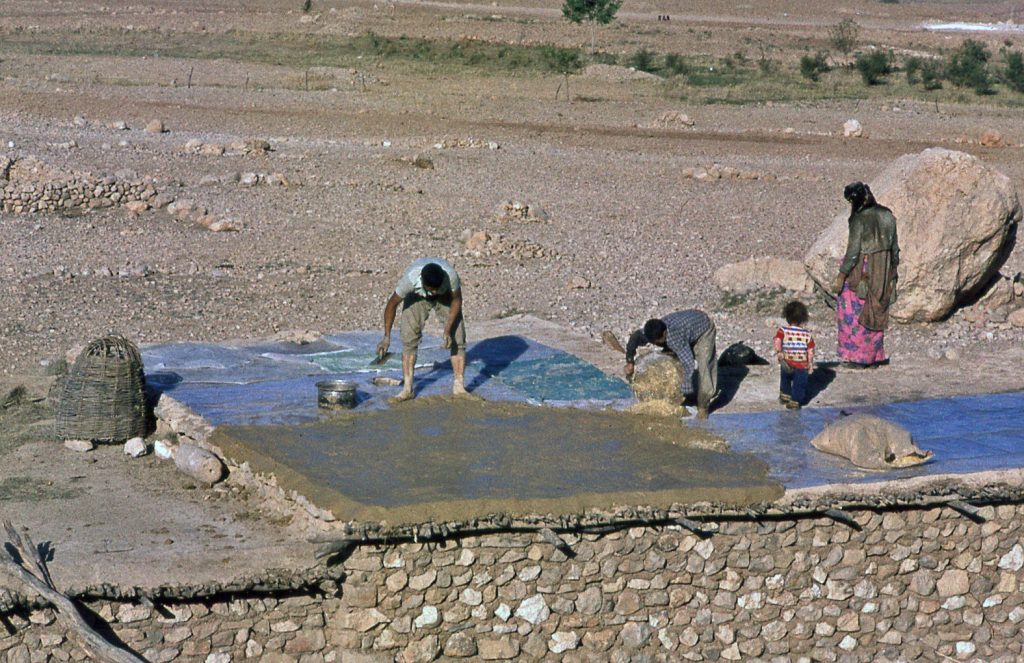

The matrix of the roof itself was traditionally laid over a base layer of small tree branches that were carried by beams. On top of the branches came a layer of brush; in the 1970s, plastic sheeting had become the preferred more economical option for this ceiling layer. Time will tell whether a plastic membrane of this kind is durable. The roof surface itself was a tamped chaff-rich mud, slightly inclined to direct rain towards a run-off spout. Once laid, the mud was trowelled smooth and worked to eliminate cracks as the mud dried. Such roof surfaces also need reworking in this way after heavy rain or a snowfall. As in the village, the flat roof of the expedition house was occasionally used for work.

24 & 25. Pouring and trowelling roofing mud over plastic sheeting.

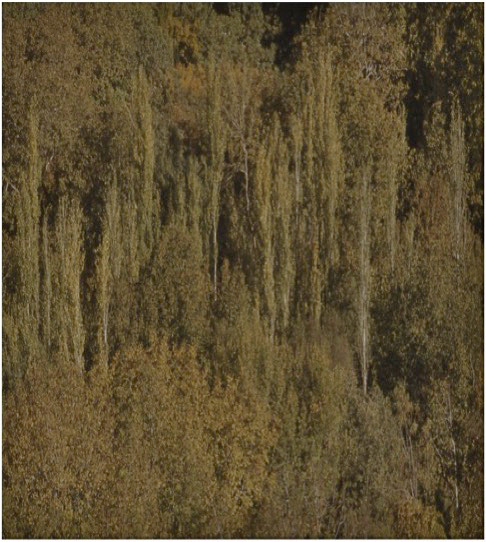

A standard finish for the interior a wall face was the application of a mud plaster. Optimally they could be white plastered and painted.

Wood is expensive. A bonanza for the project was that the Ahl Haqq community centre on the plain below – in Sar Pūl-i Zohāb – was undergoing renovations. In the process they were discarding old beams that they were happy to sell to us because they perceived them as being returned to the place of the origin in the Ahl Haqq heartland. All of these recycled beams had been painted green at the time of their original use. Some of them can be seen in the ceiling above the storage shelves.

Where a greater span was needed than could be carried by unsupported beams, uprights could be introduced to help carry the ceiling load. For the front porch of the building we used the traditional Kurdish device of a column and capital to carry the weight of the main beam span. Such an architectural feature is called a ‘tarmā’ (columned portico). The open space of this porch was often used by the Canadian team for both relaxation and work.

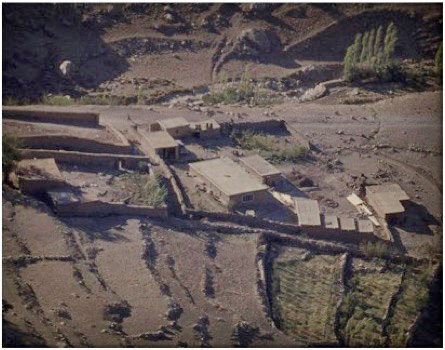

In the autumn of 1978, due to the worsening security situation in Iran (the beginning of the Iranian Revolution), I felt the need to make the Canadian compound more secure by completing its perimeter wall. Collecting field-stones for this purpose, due to the generosity of a local land-owner – Dāwar Karamkhānī – fortuitously resulted in the exposure of a Sasanian fire-temple (initially dubbed Kala Dāwar in his honour, now re-labelled as Gach Dāwar) – see Link #5. As it stood in 1979, the Canadian compound consisted of a series of work, storage and living facilities

Sadly, on examining present satellite images, it appears that the Canadian compound structures have largely disappeared, likely through the recycling of the building materials by others for their own purposes. The family of the former Canadian compound’s resident guard (Mortezā) still live in the old kitchen. The last visual record of the compound’s structures is an image taken by the Iranian Heritage Organization. The blue painted plaster on the walls of the ruined dormitory section of the Canadian compound most likely dates from the time when the Zardeh tableland was taken over by the Iranian military during the Iran-Iraq war of the early 1980s. As in ancient times, the Zardeh tableland had been judged to offer an appropriate position against attempted incursions of Iran via the Zagros Gates, by the Iraqi forces of Saddam Hussein.

However, bulldozing by the Iranian military in the 1980s, and road building, meant that the area was now much more accessible to vehicular traffic than the old village, nestled in the hollow of the Zardeh gardens. The area of the former Canadian expedition compound is completely enveloped within the new village of Bān Gomeh. Ironically, this writer was advised by the BānZardeh villagers in 1976 that building on the exposed hillside was not advisable, due to the prevalent high winds.

Migration to Summer Pastures.

With its orchard gardens and fruit trees, as well as the opportunity to graze animals in the open fields and on the mountain slopes, the old village of Bān Zardeh must always have been moderately prosperous by comparison with other small villages in the region. But, ironically in the 1970s, the villagers of the Sayyid Muhammad hamlet at the western end of the tableland had become richer. This was due to their large holdings of fat-tailed sheep, which generated substantial income through production of the fashionable rōghan ‘fat-rendered cooking oil’. Traditionally, the entire hamlet of Sayyid Muhammad was vacated in spring, flocks driven into the high summer pasture of Dalahū before the grasslands of the tableland dried up in June. The same is true for tribes from the plains of Zohāb who remarkably ascend the Zardeh cliffs on their way to Dalahū.

Some of the residents of Bān Zardeh also vacated the village each summer in the same way – as transhumant pastoralists – to take advantage of the green upland grazing lands. Black goat-hair tents were transported on mule-back. In their transhumant mode, these people lived in the tents, with reed screens providing separate spaces inside each tent, for privacy. Each autumn, before taking up residence in their houses for the winter once more, these pastoralists pitched their tents just outside the village.

In autumn, herds were grazed in fields of stubble where weeds had grown up following the wheat harvest. Wild grasses on the hillsides could also be grazed.

The Annual Seasonal Cycle.

The traditional lifestyle of the villagers of the Zardeh tableland was dictated by both terrain and prevailing climate. Medieval Arab geographers describe this extreme western ledge of the Zagros mountains as having snow in winter on the side that faces Iran, but no snow on the side that faces Iraq. This is indeed a totally valid observation in the current era. The uplands of Dalāhū are deeply covered in snow in winter, lasting well into spring. When the Dalāhū snows melt in the spring, it brings the pasture grasslands to life, as well as feeding the springs that help sustain the domestic and agricultural lives of the settled villagers on the lower ground. While it does snow infrequently on the Zardeh tableland, that snow usually burns off moderately quickly in a couple of days or so.

From roughly late November to mid-April the Zardeh tableland can expect to receive precipitation in the form of rain carried by cyclones that have the strength to move in from the Mediterranean. The hillsides are covered with grasses and wild flowers that provide rich grazing.

48 & 49. Wild flowers in April 1976.

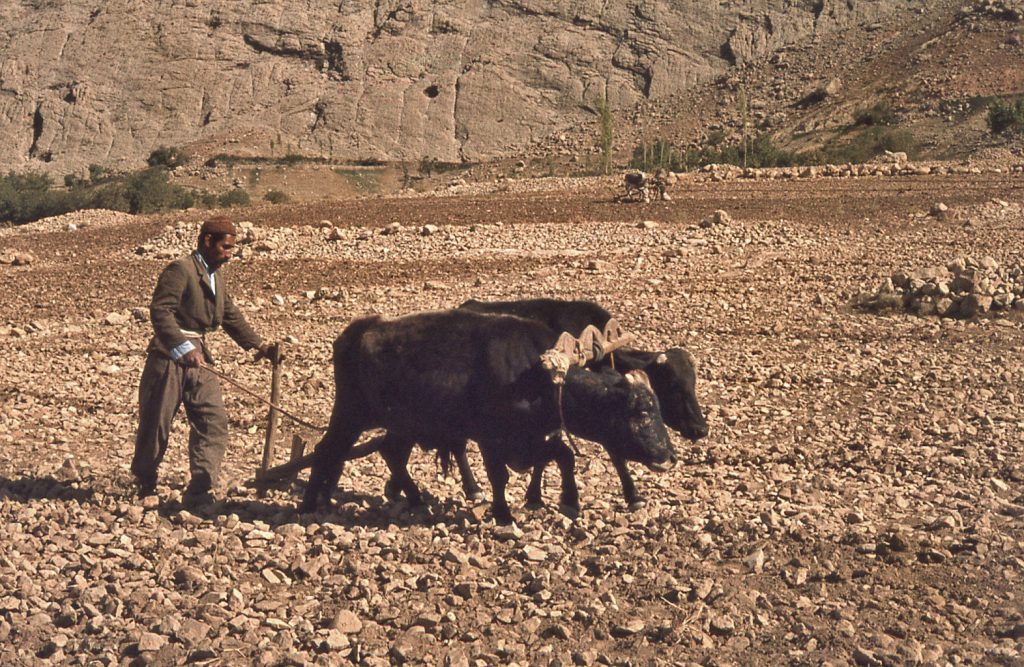

By June, the grasses start to turn brown, and the grazing potential is much poorer – hence the migrations to upland summer pastures The arable cycle fits this pattern too. In November, in anticipation of seasonal rain, the fields are ploughed. Once it rains heavily in spring, grain is broadcast by hand in a marked-out plot, and the seed ploughed under.

The first crop to be harvested is that of chick-peas. These are sown on the stoniest plots of land that are not really suitable for wheat. Harvested chick-pea sheaves are stacked on a threshing floor, pending being trampled on by a team of animals yolked together, to separate seed from stalk. Mature wheat is harvested in June. In the 1960s, a flail was still being used to thresh small quantities of harvested wheat, though teams of yolked animals were the norm.

The Tableland’s Natural Resources

For the most part, the natural resources of the entire region are fairly meagre – suitable only for sustaining a modest subsistence existence. This is why there is a need to explain what could have sustained a formidable stronghold. Admittedly, there are some natural resources that can be harvested.

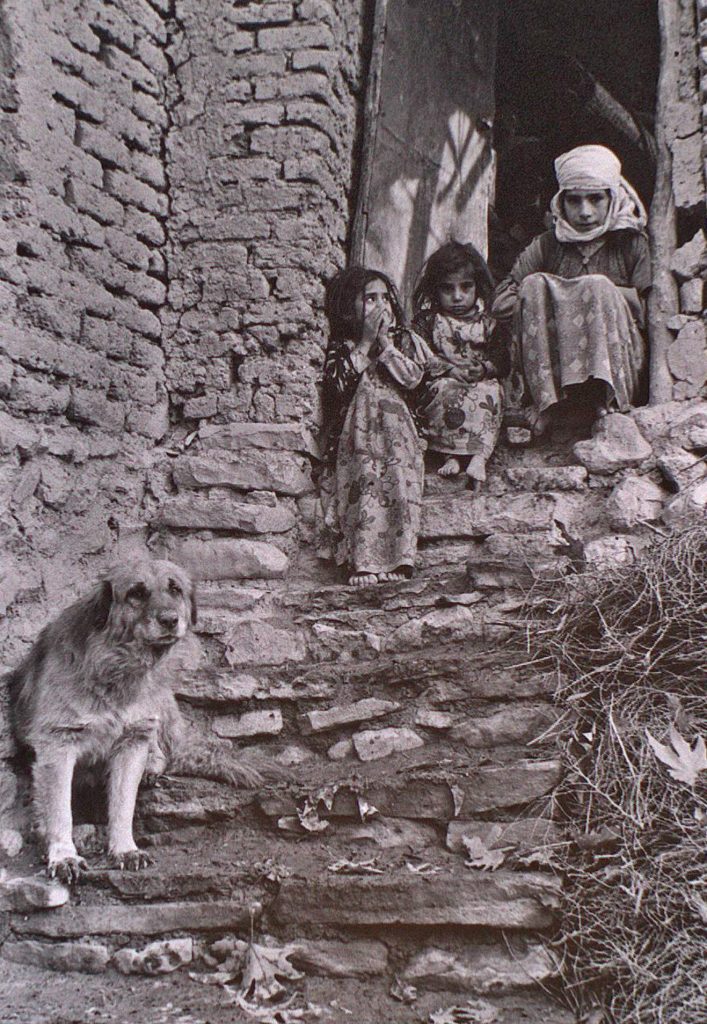

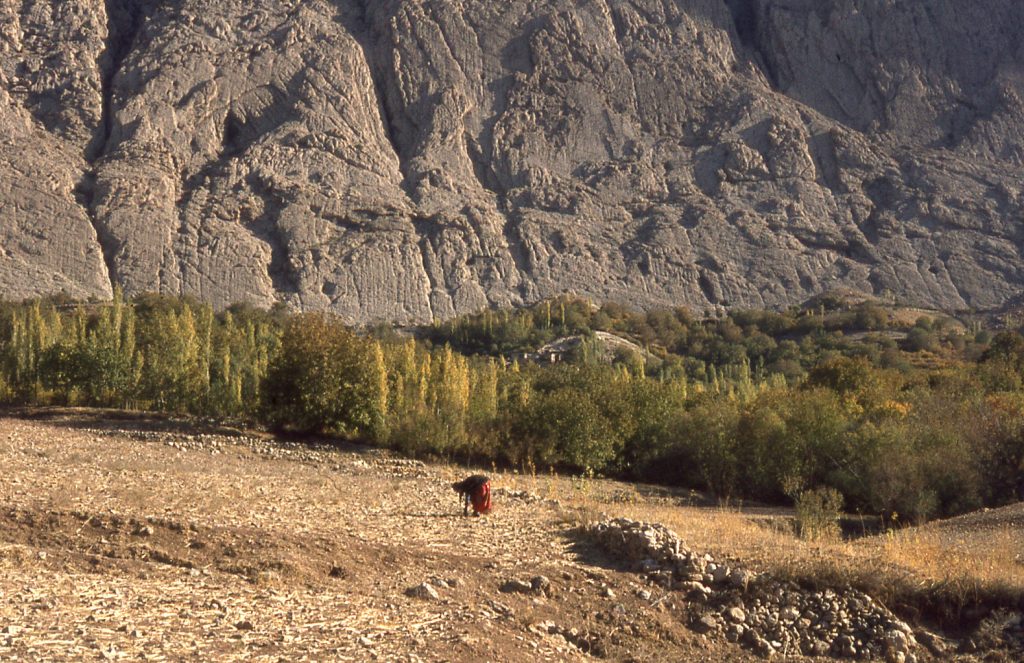

But the orchards – of walnut, fig, pomegranate and grape – need irrigation during the dry summer months, if they are predictably to bear fruit in autumn. The sycamore trees that are grown for construction lumber are planted along the banks of the steams that water the gardens, and so are well watered. Even wheat benefits from an occasional free-flow distribution of water across the field in early summer, if it is available. Only chick-peas manage to grow to maturity on the dry hillsides, because of their short growing cycle.

Nevertheless, all of these crops thrive only because of the moderately temperate climate. It is not hot or wet enough for date palms to thrive. They can only be cultivated on the plains below the tableland. Here it is much, much hotter in summer. The Zardeh villagers speak of the month of August as ‘khorma pazi’, (literally “date-cooking”, i.e. ripening in the heat). The main fruits of the Zardeh irrigated gardens are walnuts, grapes, pomegranates and figs, all of which have good storage properties.

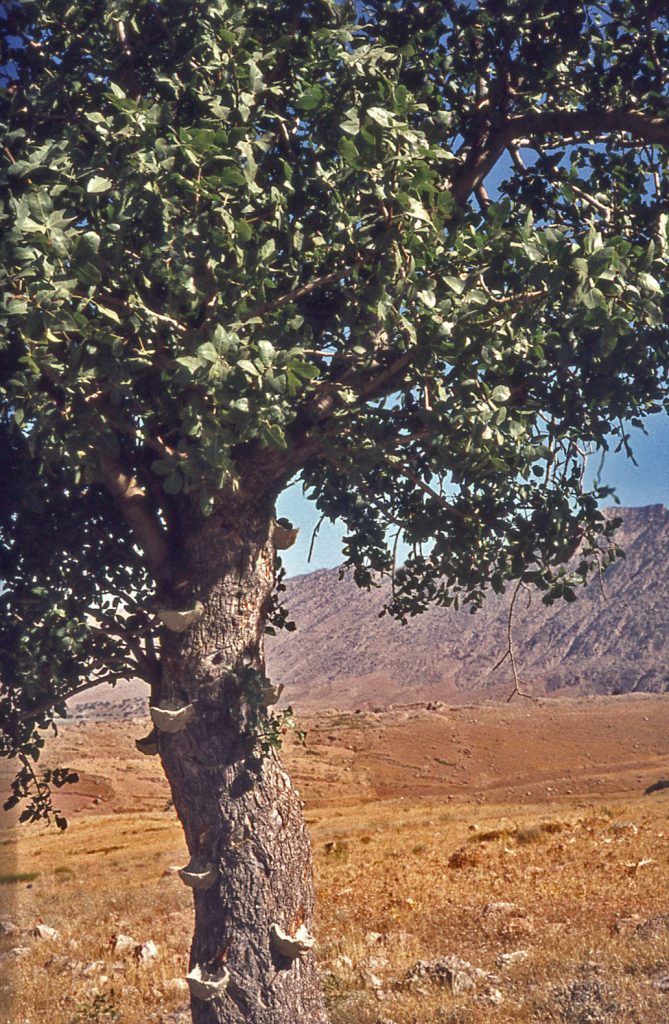

Pistachio trees grow wild on the steep hillsides outside of the Zardeh tableland.

Their existence reflects a much earlier time when the Zagros mountains were much more heavily wooded than they are today. Besides the obvious potential for harvesting immature nuts for the making of relishes, as well as mature nuts, pistachio tree trunks are tapped for their resin, as an ingredient in the making of ‘gum Arabic’.

These trees, as well as other hardwoods such as oak, were important sources of fuel. Serious deforestation of the entire Zagros mountains likely began as early as the Bronze Age when wood was vital for metal smelting. In the immediate region of Zardeh there would also have been a need for a massive amount of fuel to smelt the gypsum for building the extensive masonry structures of the Parthian stronghold. A volume ratio of two measures of wood to one measure of gypsum is necessary in this smelting process.

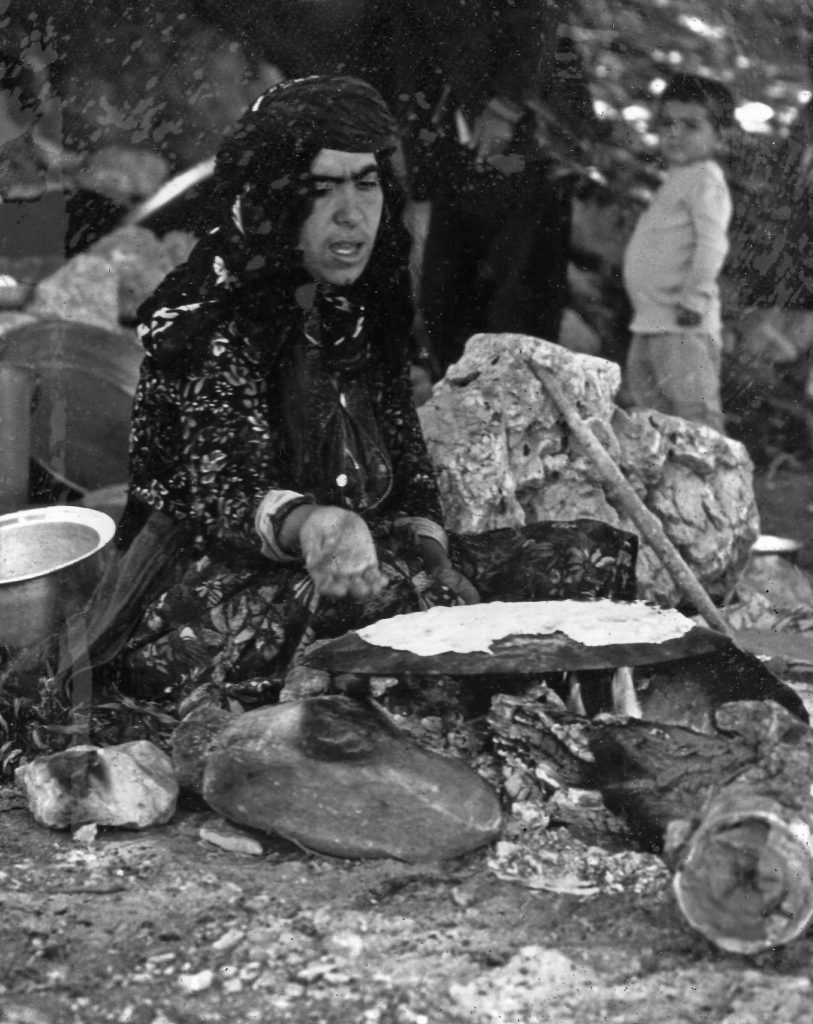

Pressure on the forests has only been slightly reduced in modern times due to the availability of fossil fuels like kerosene and propane gas. But traditional religious practices and festivals that involve the preparation of sacrificial foods will always be conducted using wood fires (see Link # 6, re Ahl Haqq). Dried scrub vegetation is routinely collected for use in tea making and the making of unleavened flat bread.

For further reading see: