Project Overview

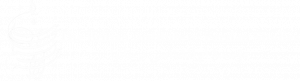

The story about what has been called ‘Yazdigird’s Castle’ (Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd), an archaeological site in western Iran, has evolved over time. The setting of the archaeological ruins is a projection that forms a natural tableland on the extreme western edge of the Zagros mountain range.

Defences built along the tableland’s western escarpment were designed to create a formidable stronghold, dominating the plain of Zohāb below. A massive defensive wall was built across the open neck of the tableland, protecting against invasion from its most vulnerable side.

Local legends surrounding this ancient stronghold in Iran associate its construction with 7th century King Yazdigird III, the last of the Persian Sasanian kings before Islam. A pinnacle-top fort that is the anchor of a formidable set of fortifications around the tableland is known locally as Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd ‘Yazdigird’s Castle’.

The site was long ago judged by me to be inappropriate for association with King Yazdigird III, due to the harassed circumstances of his reign that occurred shortly before the rapid Islamic onslaught of the Arabs. In time, I would conclude that the attributions to Yazdigird’s sponsorship of the monumental structures of the Zardeh tableland were totally false, seemingly derived from the reformist preachings of Sultān Ishāq, the early 14th century founder of the Ahl Haqq sect who likely wanted to connect his followers to their pre-Islamic Persian cultural past.

Originally interpreted by me in 1965 as a Sasanian hunting lodge or pleasure palace of the 5th century CE, the palatial monuments set within a fortified enclosure were later interpreted as the stronghold of a 2nd century CE Parthian warlord. I theorized that such a figure maintained a strategic position independent of the Parthian central authorities, sustaining a profitable living by way of extracting tolls from commercial caravans that plied the route of the nearby ‘Zagros Gates’ pass.

It is apparent that when the Sasanians seized control of Iran in the early 3rd century, they sponsored a fire-temple on the hillside of the Zardeh tableland – Zoroastrianism being the newly adopted religion of state – in an obvious expression of the idea that the era of the Parthian warlord was now over.

In early Islamic (Umāyyad) times, the region experienced some investment activity that continued on into 10th century Būyid times. But without an external source of income, the landscape could not support much more than a subsistence level of livelihood.

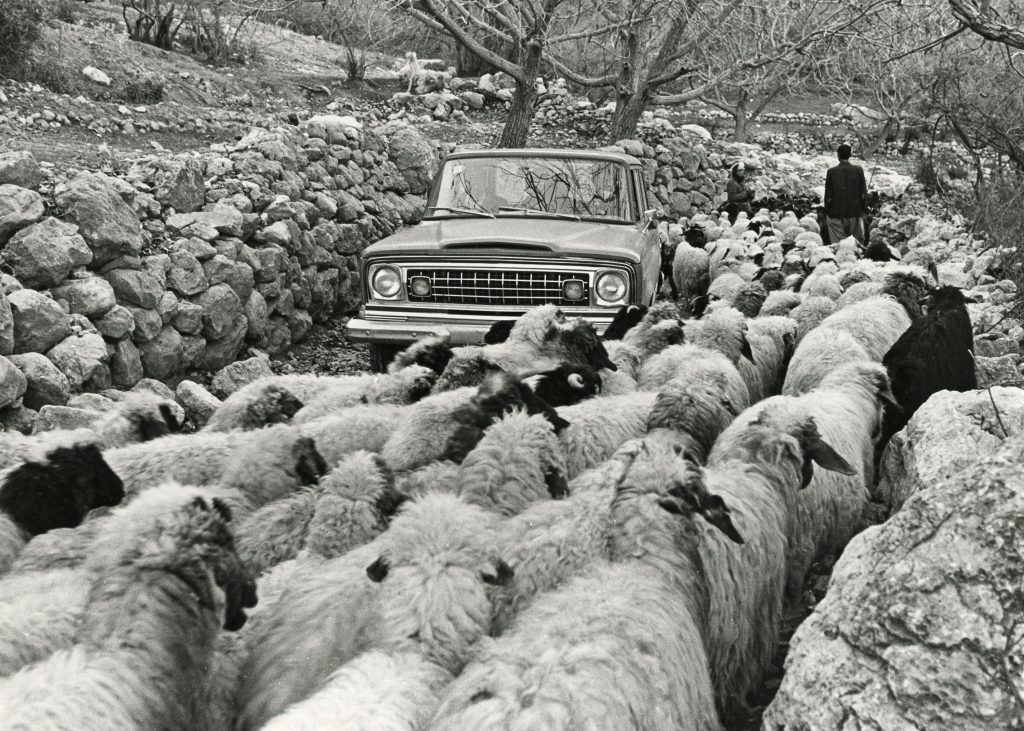

I first learned of the archaeological potential of the site from a British researcher while on my way home to the UK in 1963, after my first year in Iran as an archaeological novice. Sitting on a beach in southern Turkey, I listened intently to Chistopher Weightman as he described a formidable wall attributed to Sasanian King Yazdigird III. Hehad seen the wall while visiting the Ahl Haqq shrine of Bābā Yādgār, in a gorge beyond the village of Bān Zardeh. These villagers describe themselves as Ahl Haqq ‘People of the Truth’. Bābā Yādgār is a revered figure in their folklore.

Shaykh Bābā Yādgār was one of the original seven peers of the Ahl Haqq. According to a three-centuries-old ‘wāqf’ document(Foundation Trust – see Sultani 1382/2004) a wealthy Kurdish land-owner – ‘Amīr Qumām al-Dīn – in year AH 933 (1527 CE) donated tracts of land in support of the Bābā Yādgār shrine. He reported that the Shaykh had told him in a dream that he lived in the land of Serā-ye Zard Yazdigīrdī (Yellow Seraglio of Yazdigird). This gives us our earliest hint of the local legendary association of the archaeological ruins as being the work of the last of the Sasanian kings of kings. This website attempts to present an explanation for this improbable association. In hindsight, ‘Amīr Qumām al-Dīn’sendowment term would have given us a preferred site designation for the archaeological remains in the heartland of the stronghold. But in 1964 it was not known to me, and ‘Qa‘leh-i Yazdigīrd’ became a convenient reference name for all of the archaeological remains in the area ever after, and one used in all publications so far – but, in reality, that name only really refers to one part of the site.

Encountering Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd 1964-65

In 1963 I was trying to create an academic niche for myself in Iranian archaeology. In the hopes of making a novel contribution, I had chosen the 3rd to 7th century Sasanian era – vibrant centuries of Persian culture before the Arab armies of Islam drove Yazdigird III from his throne around 640 CE. It was in the 1960s, an era of Iranian history sorely neglected by western scholars. The site of Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd seemed to be a perfect target for me to apply some of the skills I had learned from working for others, to document some tangible traces of the ancient culture I had chosen to study.

Reference to the site was included in my successful application to the British Academy, endorsed by David Stronach, then director of the British Institute for Persian Studies, for funds to study the archaeology of the Sasanians in Iran. My first actual reconnaissance of Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd occurred in 1964.Without a bridge to cross the Rījāb river, the expedition involved using pack-mules, in the company of Iran’s Archaeological Authority’s Representative Mahmoud Aram. It was an exhilarating four-hour ride there and back, albeit making for extremely sore legs the next day (a pack-mule is ridden without stirrups).

I had some sense of the historical legends associated with the archaeological site through a report of a visit there made in 1836 by Henry Rawlinson, the famous decipherer of the cuneiform inscriptions at Bīsitūn. As a military officer of the British India Army, Major Rawlinson conducted a reconnaissance of the routes of western Iran, backing the Qājār Shah of Iran’s measures to thwart Russian intrigues in the area during the era of waning Ottoman authority in Mesopotamia (today’s Iraq). In exploring the routes around the Zardeh tableland, Rawlinson also described the archaeological ruins of the area. Because of his fame as a scholar, I was blindly led to accept at face value the legends he reported concerning King Yazdigird’s connection to the site. To me, in 1964, the physical evidence associating the Sasanians with the stronghold also seemed overwhelming, since monumental fortifications of this kind built by their predecessors – the Parthians – were virtually unknown to Iranian scholarship at that time. Because of their scale, the ruins seemed unlikely to be Parthian.

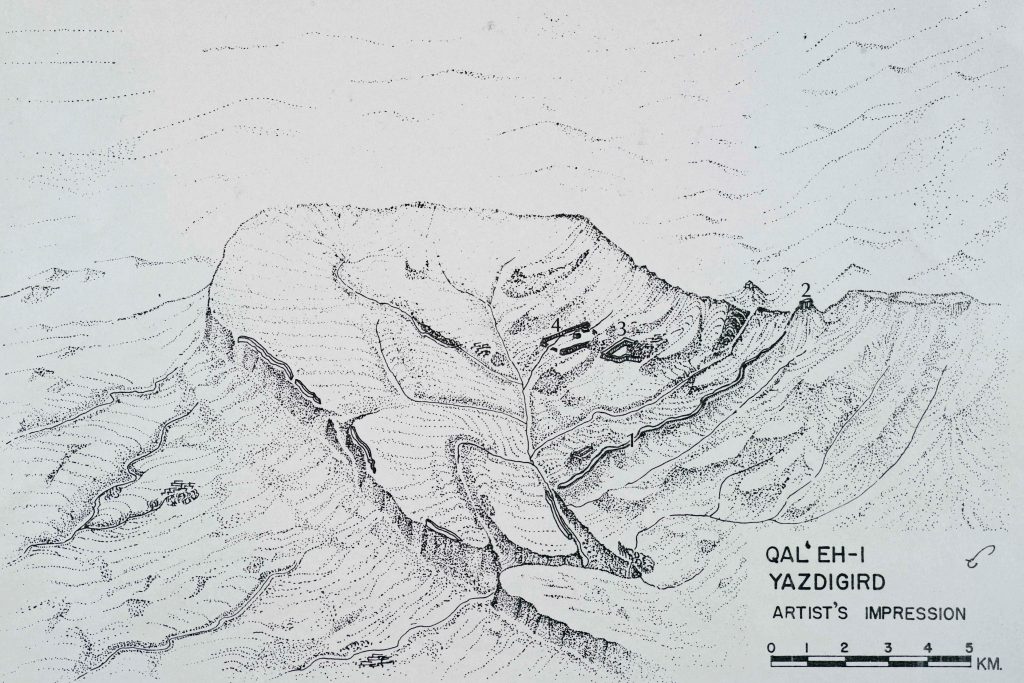

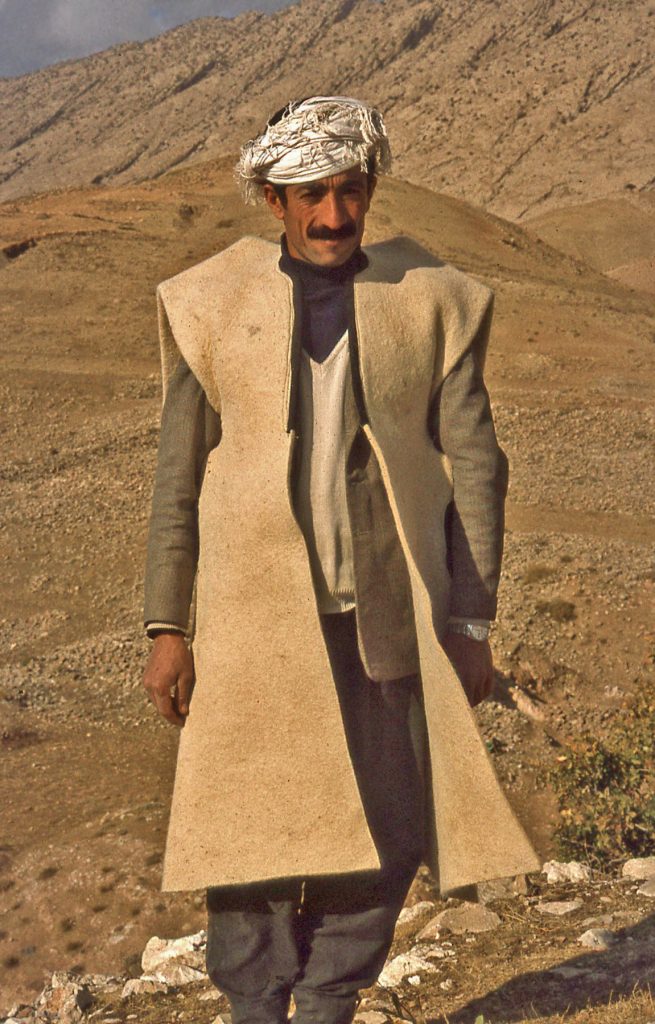

In June of 1965, with a three-week permit in hand and a modest budget from the British Institute, and accompanied by Agha Rahnamoun from the Archaeological Authority of Iran, I set off for the Zardeh tableland. There was still no bridge over the river at Rījāb, but at that time of the year it was possible to ford the river gingerly in the British Institute Land-Rover. When we reached the village of Bān Zardeh, which was to be our expedition base in the heart of the ancient stronghold, the villagers told us that this was the first time that a motorized vehicle had ever entered their village. Basically we were driving along drove-ways for herds of sheep and goats that were brought back every night to the village from their grazing lands.

In the 1960s there were no satellites to provide the images that we take for granted these days, and even aerial photographs that archaeologists standardly used at that time for getting bird’s eye views of sites, were off-limits to us for security reasons – due to our proximity to the Iraqi border. Despite the challenge of having to measure a defensive wall some two kilometres long, I used an army surveyor’s compass and a fifty metre tape held at one end by local hunter Muhammad ‘Ali – who knew the landscape intimately – to make what was a moderately credible sketch map of the area.

Apart from documenting the dramatic stronghold fortifications, which gave the archaeological site its identity, my aim was to explore for clues about the nature of the settlement. This meant looking for the telltale traces of occupation that often come in the form of fragments of pottery (potsherds) lying on the surface of the ground. Traversing the terrain while making the map I had observed the all-important potsherds in parts of the site on the surface of the ground, especially on a hillock locally called Tepe Rash.

I quickly became frustrated by the fact that there were ample potsherds on the surface of the Tepe Rash hillock, but – in digging down – none were preserved below the surface. In other words, the settlement of that particular spot had probably consisted of ephemeral structures that left no tangible occupational trace, possibly having involved the use of tents in autumn, in the way today the pastoralists of the tableland temporarily encamp in the area before winter. Everything but the imperishable pottery had disappeared over time. My workmen, residents of the village of Ban Zardeh, sensed my frustration and volunteered the idea that I should dig in the field they called Gach Gumbad. In Persian, ‘gach’ means “gypsum plaster”, and ‘gumbad’ means “dome”. I first had the fantasy about the survival of a memory of a plastered dome from antiquity. The reality was different.

When, from time to time, the Ahl Haqq villagers of Ban Zardeh needed to repair the dome of the Bābā Yādgār shrine, they were accustomed to mining for gypsum in the field of Gach Gumbad. Gypsum – which is calcium sulphate – once mined and rendered into plaster is infinitely recyclable, simply by re-smelting in a furnace. The heat breaks down the molecular structure and turns the material into powder once more, which then can be mixed with water and made into plaster again. As it turns out, the gypsum lumps that the villagers had been extracting for re-smelting were once ancient architectural ornament.

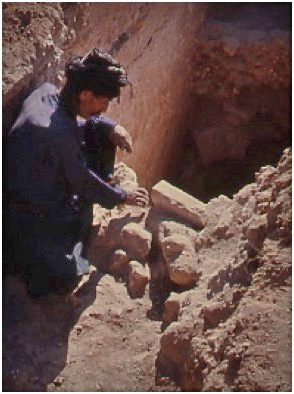

From my archaeological excavations in the field of Gach Gumbad, numerous fragments of decorative plasterwork and even an intact decorated wall face were exposed, beginning just below the field’s plough line.

The ruined building buried

below ground was positioned at the top end of a rectangular enclosure called

locally Maydān, meaning “Yazdigird’s

Parade Ground”, but a feature that imparted the sense of a walled garden. The

lavish nature of the building’s plaster ornament is best seen as the wall

decorations of a palatial pavilion set at the head of a ‘garden of

paradise’. A massive, but enigmatic tower-block of mostly solid masonry was set

at the garden side of the pavilion area.

In Parthian times it is most likely that the Maydān area was irrigated by a stream drawn from the spring that flows out of the mountain where the Bābā Yādgār shrine is located. Recent investment by the Iranian Government has resulted in an engineered canal drawn from the Rījāb river that considerably increases the irrigational potential of the Zardeh tableland (particularly for the growing of olive trees). In Parthian times, the only likely supplemental source of water was a stream diverted from its spring source in the nearby settlement of Yārān. But I found no evidence of a canal from Rījāb in Parthian times.

In the operation, I had not found the pottery and the traces of settlement activity that I had been looking for, but I had landed accidentally upon a fantastic storehouse of ancient plaster decorations. This treasure-trove of architectural ornament cried out for more attention. But I was not able to find financial support from the British authorities to sustain the activity. I sought the means to continue my career in Parthian and Sasanian archaeology through allying myself with North American institutions.

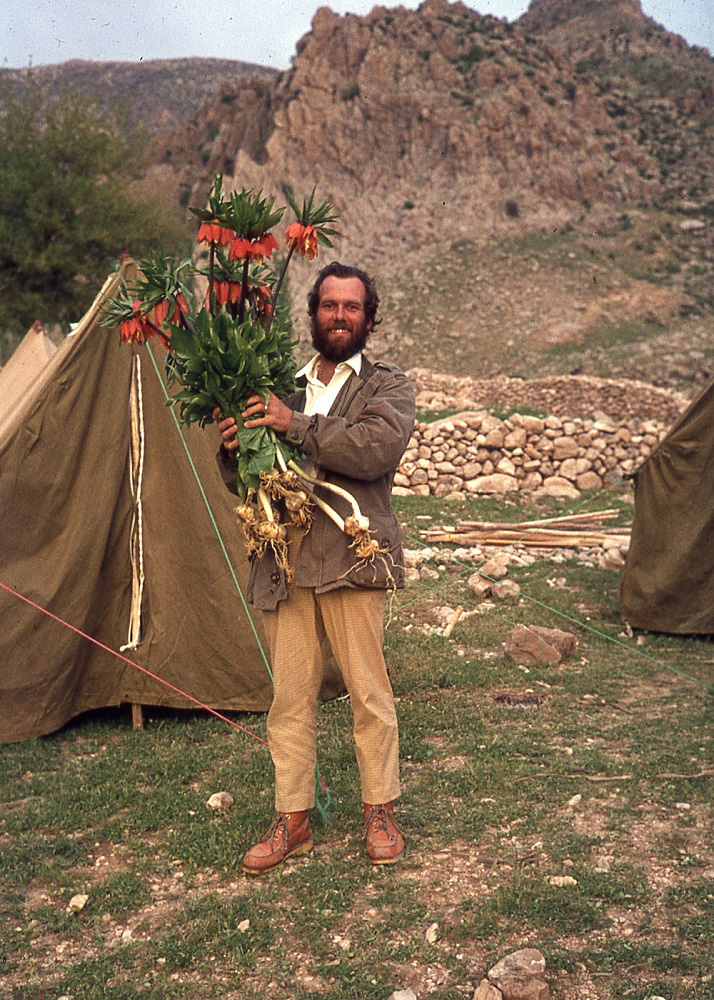

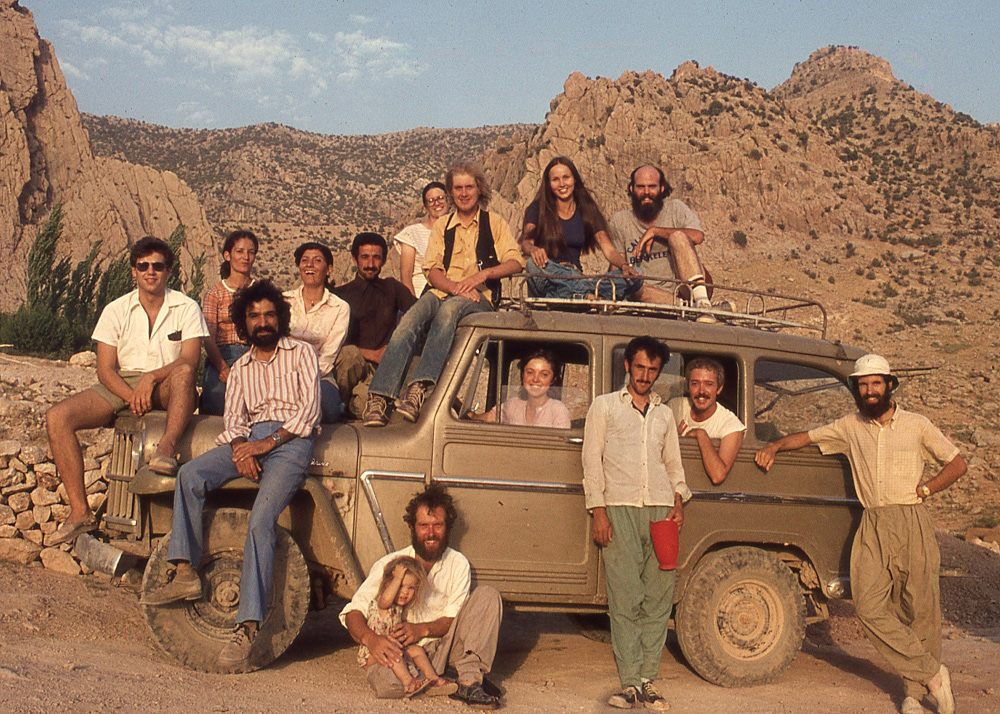

Canadian Expeditions 1975-79

Almost ten years after my work at Gach Gumbad, I was appointed to a curatorial position at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in Toronto, Canada. I presented a proposal to the Iranian Antiquities Authorities for re-activating the work of the Qal‘eh-i Yazdigirdprogram. The Director of the Archaeological Authority, Dr. Firuz Bagherzadeh, graciously over-looked the fact that technically my permit had long since lapsed. Out of goodwill, permission was awarded in 1975 for a new expedition in the name of the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM). There were three full-scale Canadian expeditions working at the site before the unexpected collapse of the program in February 1979.

In 1975, knowing that there was a vast store-hold of plaster ornament in the field of Gach Gumbad that needed huge resources and logistical support for excavation, study and conservation, I opted to avoid the decorated rooms. I applied the energies of that season of work to probing outlying areas, particularly alongside the main defensive fortification wall, as well as documenting the fortifications themselves. The aim was to characterize the nature of the site’s occupation overall. But despite the deliberate aim to avoid the recovery of architectural ornament during that 1975 season of exploration, more pieces of ornamental decorations accidentally came to light.

A low mound was targeted for examination just outside of the Maydān garden enclosure, in an area locally called Hushtāreh (Thorn Bushes), in the hopes that the investigation would reveal some trace of the nature of the settlement. The mound turned out to be mostly a heap of deliberately dumped architectural debris. This was a principle not fully appreciated at the time. As learned in the 1978 season, the fragments of ornament had been cleared at some time from the Gach Gumbad palatial pavilion. But the unearthing of the artwork did set me on course for returning to assess the date of the artwork that was increasingly becoming of huge significance – both for its intrinsic artistic merit, as well as for understanding the date and significance of the ruins.

I gradually had to acknowledge that even a modified Sasanian date of the 5th century for the site was completely erroneous. The artwork being unearthed was clearly of a previous Persian cultural era, namely that of the Iranian Parthians of the 2nd century CE. What I had originally judged to be ‘archaistic’ elements in the artwork (namely “looking back to the past”) could be seen fitting well with a 2nd century time attribution. The elements that were plausibly 5th century in date were in fact ‘futuristic’ (namely “innovative for their time”).

The practical reality of the 1975 discoveries of extensive evidence of elaborate artwork irrefutably highlighted the fact that the original 1965 ceramic project had morphed into one where a major effort needed to be directed towards the exposure, recording and preservation of potentially thousands of pieces of architectural ornament. That was the major objective of the 1976 expedition. It furnished the bulk of the artwork that has provided the basis for the identification of Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd as the stronghold of a Parthian warlord.

Acknowledging the architectural ornament as a major priority changed the whole logistical approach that needed to be taken in order to run an effective expedition. The British team of 1965 had been accommodated in the Bān Zardeh schoolhouse. The first Canadian mission of 1975 was accommodated in tents set outside of the village, on the roof of bee-keeper Rustam’s house. But the extensive ROM project that was envisaged for the future needed more extensive housing for its expedition members – nowhere was there suitable space available in the village, and there were no toilets or bathing facilities. There also needed to be adequate workspace for recording and conservation of the decorations, as well as for storage. In the spring of 1976 I opted to buy from a local landowner (Dust ‘Ali) a piece of barren space on the open hillside to build an expedition house, in the area called Bān Gomeh. One major attraction in the choice of this piece of land was that it had no agricultural value, but it had a permanently flowing stream running through it. This meant access to ample water for cleaning archaeological objects, if needed, and also washing water for the personal needs of the expedition members

The 1977 Canadian expedition involved more expedition house building, and conservation and recording of the ornament unearthed in the 1976 season. Sadly, today, the former ROM dig-house is now mostly either derelict, or demolished for re-use of its building materials.

Curiously, when I chose the site to build a dig-house I was advised that it was not a suitable place to build, because of the potential of violent winds. From a satellite image to-day one can see that the once isolated ROM compound is now surrounded by dozens of houses and a school – seemingly because the area is so much more conveniently accessible, because of a paved road, and therefore attractive for settlement.

Insights and New Challenges from the 1978-79 Expedition.

During the expedition of 1975, there were hints that the palatial pavilion of Gach Gumbad had experienced more than one decorative scheme before its demise – because of our discovery of architectural debris dumped in Hushtāreh, outside of the Maydān enclosure. This principle was reinforced in the winter of 1978, when excavations were conducted in what is best described as an arcade at the top of the gardened enclosure, west of the palatial pavilion. The arches of the arcade had collapsed, and the entire space was filled from floor to roof with building debris, seemingly cleared from the decorated pavilion.

The implications of this discovery are that the palatial garden pavilion was not a creation of a single, limited duration. In other words, in all likelihood, more than one Parthian lord sponsored building activity connected with the structures of the garden pavilion, possibly over the time span of a century or more.

In addition, one cannot discount the idea of a hostile response at some time to the existing decorative scheme. Leading to this hypothesis is the discovery in the dump-filled colonnade of a female bust portrait. It had been defaced and plastered over while it was still on the wall. Ultimately it was removed from its original site, during demolition activity following likely natural earthquake damage to the structures of the palatial pavilion. Why the portrait was deliberately defaced, and what were the circumstances of its final demolition, are both a complete mystery at this point.

It is apparent that the Gach Gumbad tower-block also suffered severe earthquake damage, at the same time as the pavilion. Seemingly, the tower-block must once have been a commemorative monument, in keeping with the so-called victory monument of the Sasanian King Narses at Paikulī, not so far away in Iraq. The evidence for this is the survival of decorations on a face of the original tower-block. After the structural damage, another articulated façade was added, obliterating the original decorated façade. Included in the inventory of ornamental debris dumped in the Maydān colonnade is a piece of ornament that had once embellished the original face of the tower-block of Gach Gumbad. The fragment involves a running vine-scroll with human bust portrayed within the vine.

Part of a similar panel is still preserved on the original tower, hidden in a fissure on the side of the tower-block, but discernible because the added masonry has pulled away from where it was attached to the original block. The articulated addition to the tower-block after the damage, clearly indicates continuing investment in building activity. But, at this stage in the enquiry, whether this represents Parthian or Sasanian activity is a moot point.

Exposing a Zoroastrian Fire-Temple

I have made it a habit during my archaeological career to try to visit a site at different times of the year. That way one has a better idea of the climatic conditions that the ancient residents would have experienced. After the idyllic autumn weather when the fruits had ripened in the orchards, it was a shock to wake up one morning in late December to see snow on the ground.

Good progress had been made on all fronts in that 1978 autumn season, in spite of the fact that the Iranian Revolution started to gain full momentum. In the immediate region where we lived and worked, centuries’ old scores were being settled – involving deep urban-rural rivalries as well as fights over religious ideology. But we were caught up in these conflicts because they affected daily operations like buying food in the town of Sar Pūl-i Zohāb, or going to collect money from the bank in Kermanshah.

During that winter of discontent – November-December 1978 – I was apprehensive about the security of our camp in this unsettled time and decided to build our ROM compound wall higher. Rather than just a property line marker, I wanted a protective barrier.

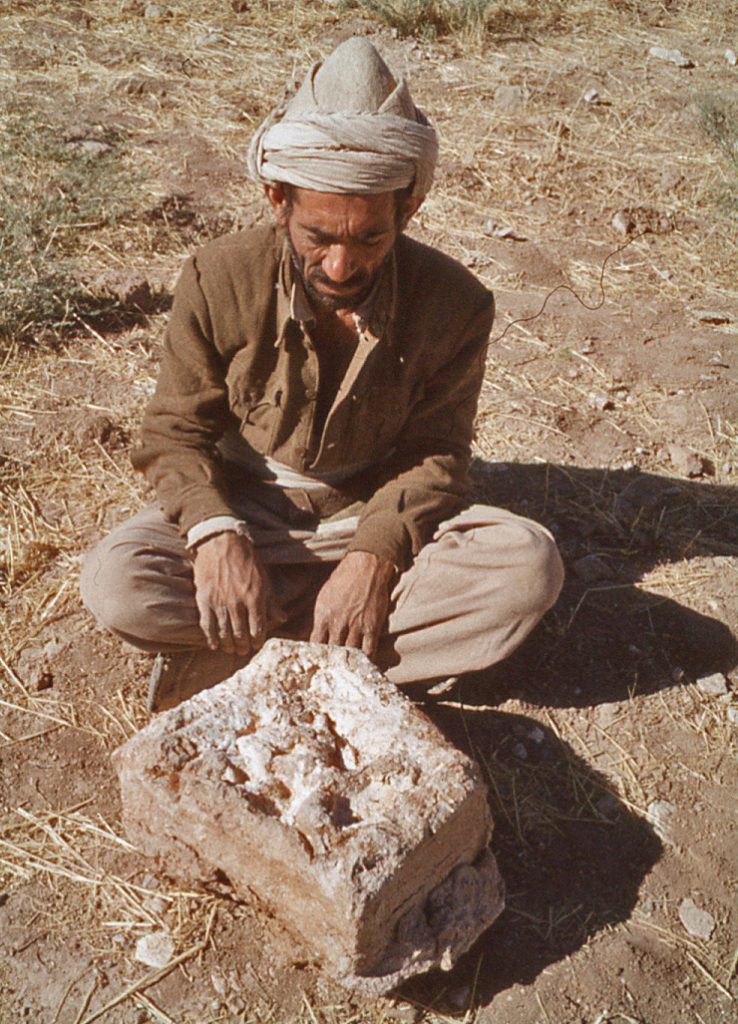

But where to get the necessary stone to build the wall? We had already combed the hillsides extensively for the freely available fieldstones. My main agent in the entire operation of the archaeological project was a local villager – Dāwar Karamkhānī by name – who happened to own a piece of land not far from the ROM dig-house. He volunteered the fact that in one of his fields there was a huge heap of stones that he was happy to have us remove for building purposes. Stones in the field were an impediment to growing crops, so that ploughed-up stones were thrown on top of an existing heap that grew with time. To honour the man who had generously given us access to the stones, the site has now been classified as Gach Dāwar.

It soon turned out that the heap was there because there was the remnant of a building underneath. On removing the loose stones on top of the heap, the traces of the original structure quickly began to appear.

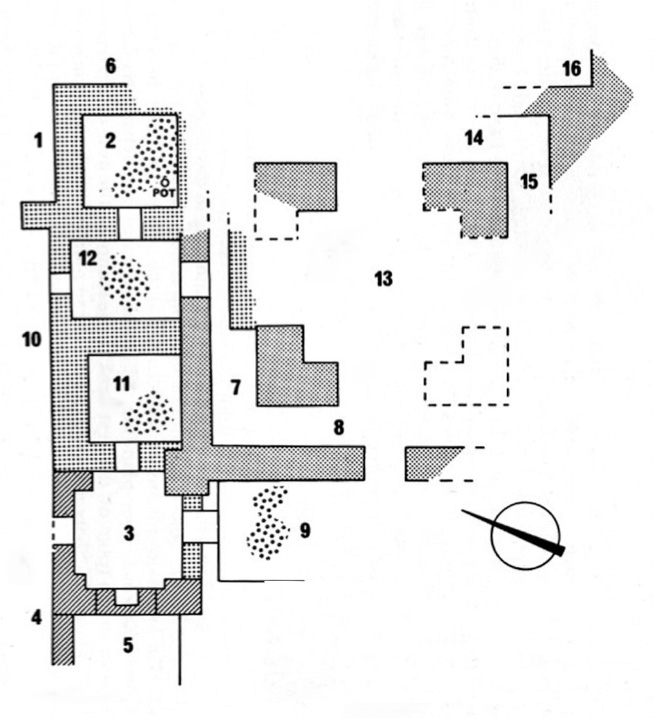

It then became apparent that the ruin had the remains of four distinctive L-shaped piers, a so-called “chahār-tāq”, whose distinctive ground plan is a classic indicator of a domed Zoroastrian fire-temple – the kind I had studied in my first years as a novice Iranologist while visiting sites in the province of Fārs. The unexpected discovery did in fact imply that a date of the Sasanian era could be applied to parts of the site after all – despite this writer’s conviction that the majority of the structural remains of Yazdigird’s seraglio were dated to the earlier Parthian era.

So what is the explanation for the presence of the fire-temple? To answer this question, we must acknowledge that Parthian culture had been an eclectic mix of ancient indigenous Persian and Greek tradition – as well reflected in the decorations of the warlord’s palace. When the Sasanians overthrew the Parthians in the early 3rd century CE they adopted a specific policy of promoting the religion of Zoroastrianism, as a symbol of state authority. Fire-temples were a visibly strong part of the Sasanian identity. The best explanation for the fire-temple in ‘Yazdigird’s Seraglio’ is that it represents Sasanian termination of the Parthian warlord’s independence in the 3rd century CE. The clear message was that a new state authority controlled the region from this point on.

While the original objective of the work in November 1978 had simply been to collect stones for building purposes, all of the energies and resources of the expedition were now applied to exposing the fire-temple. The interior of the fire-temple was not explored because the sanctuary appeared filled with fallen debris, from the collapsed dome. Most of the Canadian expedition’s attention in 1978 was applied to the rooms on the western side of the fire-temple complex, which at the time were judged – based on the artifacts unearthed in them – to have been workshop rooms added in Islamic times, built alongside a derelict and abandoned Sasanian fire-temple.

These rooms had been deeply pitted by robbers looking for treasure. They appear to have been successful – for they discovered and broke open what may be called a treasure pot that had been buried below a plastered floor.

In 1978, based on what was found in the excavated debris, it was concluded that these rooms had been built as an addition to a derelict fire-temple in Islamic times. However, it is clear now that this interpretation was off the mark – due to the findings of an Iranian mission (directed by Yousef Moradi of the Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization) that was commissioned in 2007 to further examine the fire-temple. Modern building activity in the area around the ruin was threatening its preservation. The Iranian team ascertained that the fire-temple had undergone two phases of major construction, as well as minor building modifications. The new work did reinforce the idea that the ancillary rooms examined by the Canadian team of 1978 had indeed been used in Islamic times – but that their original construction had occurred in Sasanian times, as part of the operation of the fire-temple. Furthermore, even the sanctuary of the fire-temple continued to function for liturgical purposes well into Islamic times. The most recent date for use of the fire-temple, before its ultimate demise due to building collapse, is furnished by a coin dating to the Buyid era of the 10th century which was recovered from beneath the collapsed debris. Attesting to the fact that the fire-temple functioned for three centuries, before its final demise, is the presence on the central fire-altar podium of ash still preserved in a trough designed to hold ritually the ashes collected from the burning of the sacred fires.

For further reading see:

For more details concerning:

Traditional village architecture, see Land Use page

Zardeh tableland ruins and excavation trenches, see Ruins page

Architectural stucco decorations, see Architectural Decoration page

Zoroastrian fire-temple, see Fire-Temple page

Ahl Haqq culture and religious beliefs, see The Ahl Haqq page

Parthian and Sasanian government, see Parthian and Sasanian Government page