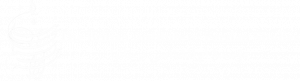

The people of old Bān Zardeh and its surrounding region are members of the Ahl Haqq faith ‘The People of the Truth’. Men often sport a distinctive handlebar moustache which is seen as a sacred mark of being Ahl Haqq.

Definition of the faith derives from the fact that as early as the eleventh century CE a religious reformer named Shāh Khoshīn promulgated in the region of Luristan, some tenets about his ideas concerning appropriate social and religious behaviour. This was a time when the Seljuq rulers of Iran were trying to promulgate Sunni orthodoxy. Shāh Khoshīn was without question a Shi’ite, strongly influenced by Sufi mystical ideas, and most likely inclined towards the idea that the ways of Iran from the time before Islam were not necessarily to be dismissed just because of Islam.

In the early 14th century, a figurehead named Sultān Sohāk/Ishāq promoted the Ahl Haqq cause in an area that is today very close to the border between Iran and Iraq, in the district that is best classified in today’s world as that of Pāveh. He gained acceptance from the local people, and the centre of gravity of this new religious movement can readily be defined as ‘Kurdish’, although the 14th century definition of a ‘Kurdish’ identity was not then so specifically synonymous with current ‘Kurdish’ national aspirations. ‘Kurds’ in those days were simply people of the western Iranian highlands.

Sultān Ishāq’s main treatise spelling out Ahl Haqq beliefs is to be found in his Kalam-e Saranjām text; our best commentary is to be found in Hajj Nematollah’s early 20th century Firqān al-Akbār. Sultān Ishāq is buried in Paveh, some seventy-five kilometers to the north of Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd as the crow flies, where Hawrāmi Kurdish is spoken. After Sultān Ishāq, the Ahl Haqq faith spread into the northwestern reaches of Iran and eastern reaches of Turkey, until suppressed during the Safavid powerhouse era when all aspects of unorthodox Shi’ite practices were vilified. Yet with the demise of the Safavids in the 17th century, the Ahl Haqq faith experienced a resurgence. Reforms to the original doctrines had been made by a Turkish preacher, Ātesh Bey who disappears from our screens around 1700. Our knowledge of these reforms comes from Ātesh Bey himself, so we have to be cautious about taking his words literally.

There was a subsequent resurgence of the faith during the 1950s, particularly in the sophisticated urban context of Tehran, though the ideas were not well received by the shaykhs and sayyids of the Ahl Haqq faith in Kurdistan. Yet in the 1960s the son of a reformer, Nūr ‘Alī Ilāhī by name, promulgated a text that spelled out the tenets of the Ahl Haqq faith. He makes reference to the traditions of the Ahl Haqq, but for which we only have recounted renditions of the original recited poetry. There are no canonical texts that survive from the Sultān Ishāq period. There is clearly in the work of Nur Ali an attempt to appease the Shi’ite clerics who are approved of by the government authorities of Iran, to lessen the sense of the Ahl Haqq being ‘other’. To give a sense of this change of interpretation, in the original tenets of the Ahl Haqq, Shāh Khoshīn and Sultān Ishāq are denoted as human incarnations of the Divine Creator. This divine essence had had a series of successive manifestation in human form, from the time of Adam onwards. ‘Ali ibn ‘Ali Talib, son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad, was held to be one of these manifesations in the so-called ‘Second Epoch’. In the new scheme promoted by Nur ‘Ali they become ‘saints’, which is more in keeping with the tenets of mainstream Shi’ism.

Very much in keeping with Sufi beliefs, a person makes progress through various experiences until they finally reach some union with an entity that we can conveniently call ‘god’. In the final stage of Ahl Haqq enlightenment, people reach the stage of the ‘the Truth’ (hence the term for the faith). This truth has been handed down over generations from the time of ‘Alī, the son-in-law of the prophet Muhammad. Iranians often mistakenly refer to the Ahl Haqq as ‘Alī Alāhī – that is, worshippers of ‘Ali. ‘Ali is a figure highly revered in Shi’ite Islam and definitely seen by the Ahl Haqq as the perfect figure to emulate. For sure, when I first visited the area of Zardeh in the 1960s, the normal greeting on meeting someone was Yā ‘Alī (an exhortation to ‘Ali), rather than the normal universal Islamic greeting of Salām ‘Aleikum ‘peace be upon you’. Even physical acts of exertion, like lifting a heavy rock, were preceded by the Ya ‘Ali expression, to assist in the effort.

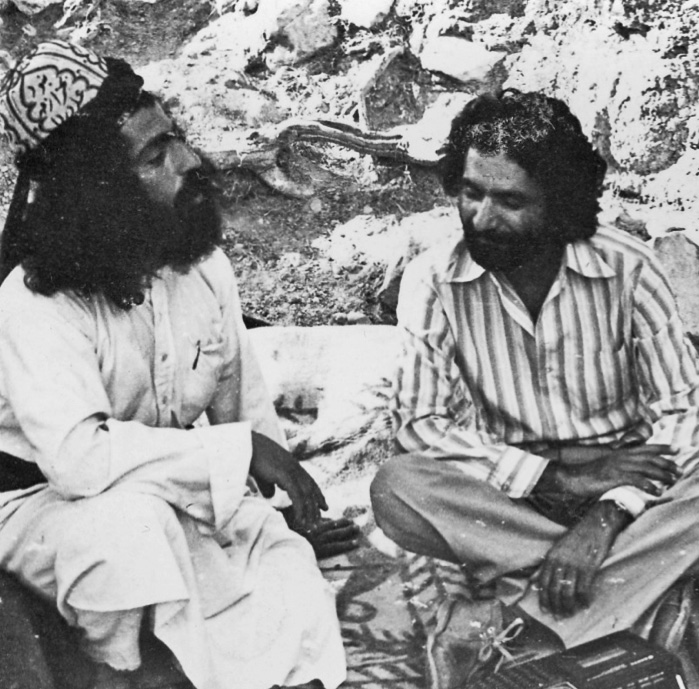

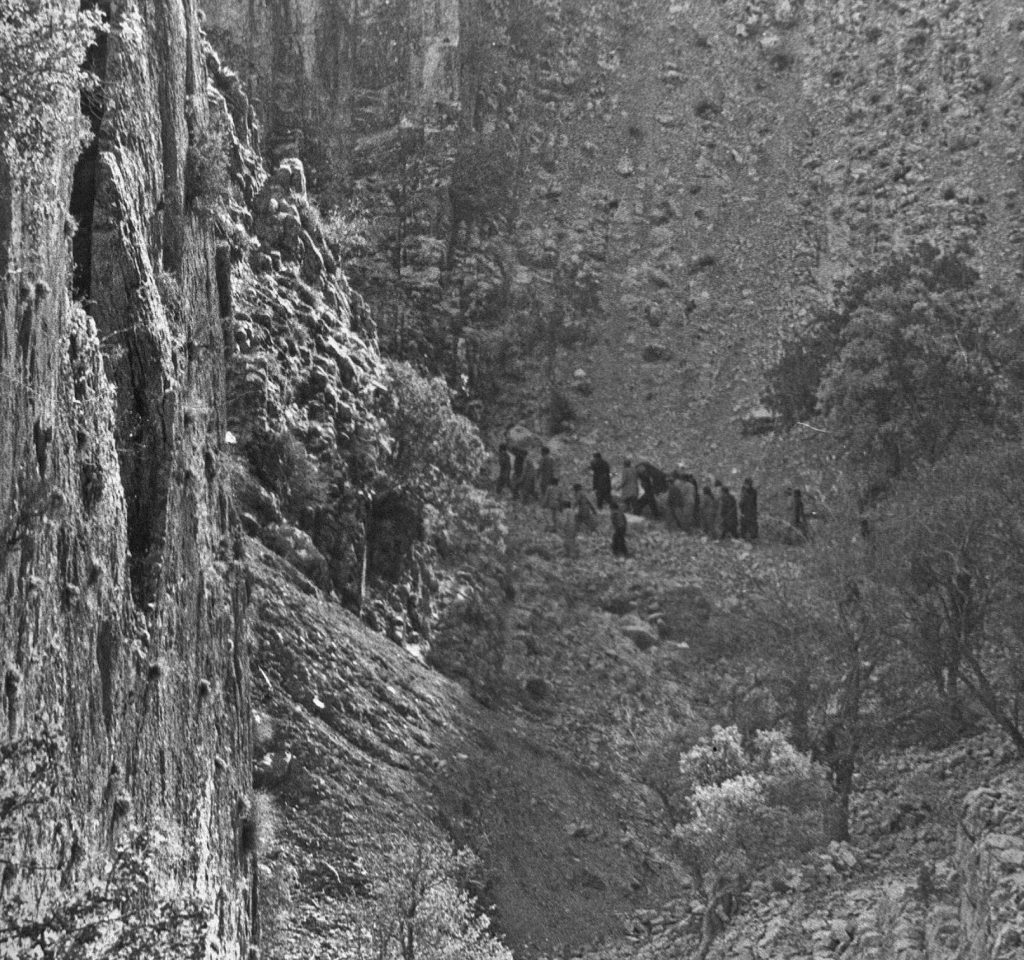

In the 16th century, Bābā Yādgār was one of the Ahl Haqq sect’s revered seven companions (Haftān). Bābā Yādgār’s tomb lies in a pocket of the mountains that form the back-drop of the Zardeh tableland.

This enclave has been formed in geological time by the erosion of the ground around a spring that flows from the mountain. Such pockets, formed by spring erosion, are a common phenomenon in the Zagros mountain range, reflecting a process that has been going on for thousands of years. Fortuitously, the spring stream flows down through a gorge that is has created over time, watering the village of Zardeh and the tableland. Locally, Baba Yadgar is given credit for having created the stream. There are actually two springs, each one maintained as offertory shrines by two different groups of the Ahl Haqq sect. One may observe people sitting in reverence beside the springs, one dedicated to Hanīta (the goddess Anahita), the other named Ghasiān. Metal vessels are placed in the spring water as offering gestures.

For the most part, for the Ahl Haqq, religious and spiritual observance following the principles of mainstream Islam does not play a part in their lives. The Ahl Haqq faith promotes the idea of the need to respect and honour everything that has been created, no matter what its nature (a sort of ‘environmentalist’ attitude in today’s world). One should also behave appropriately in this world in a way that one can reap the benefit in the next world. There are no social hierarchies for the Ahl Haqq. All people are equal. Of course, there are hierarchies dictated by the religion.

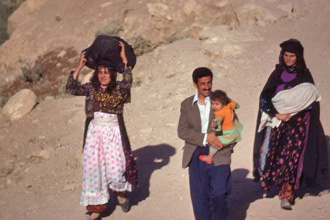

In the Ahl Haqq faith there are specific injunctions to hold social gatherings. This is called a ‘jam’ ‘gathering’. The place where these communal events take place is called a ‘jam khāneh’ ‘community hall’. In a jam khāneh there can be a communal sacrifice, where animals are ritually slaughtered and prepared for a communal sacrificial event. There can also be chanting of ritual verses, called a ‘dhikr’. Along with the dhikr chanting there can be music played on the stringed ‘tambour’ (in European terms, a ‘lute’).

During the course of the year, there are festivals in which everyone in the community participates by visiting an imāmzādeh, the grave of a holy man. The events take place according to seasonal moments in a year, such as a harvest festival. The events are solar based, not lunar. Everyone participates. The events can include music and dancing.

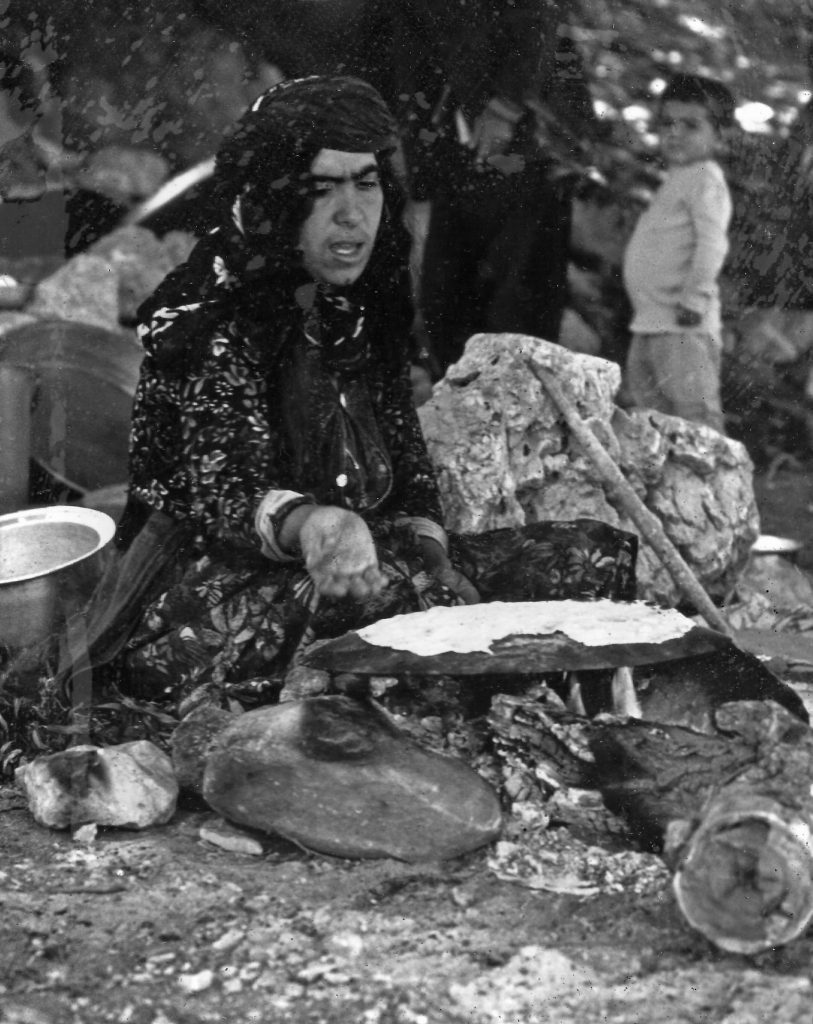

Animals are also sacrificed for the communal ceremony, involving the boiling of animals without breaking their bones and distribution of the meat wrapped in flat bread, literally in today’s gastro parlance ‘a pulled meat sandwich wrap’. Every individual receives their own ‘sacrifice sandwich’. The cooked meat is pulled from the bone and wrapped in the ritually prepared flat bread by those members of the community who are accredited as sayyids – that is, men descended from the Khāndān family lines that were founded by Sultān Ishāq.

I was always welcomed warmly by the people of Bān Zardeh, from my very first encounter with them in 1964. The Canadian expedition members participated in several of the Ahl Haqq festivals. My last encounter with the community was in February 1979, including helping bury young men who had died in the upheavals of the Iranian Revolution.

The Ahl Haqq legends of King Yazdigird

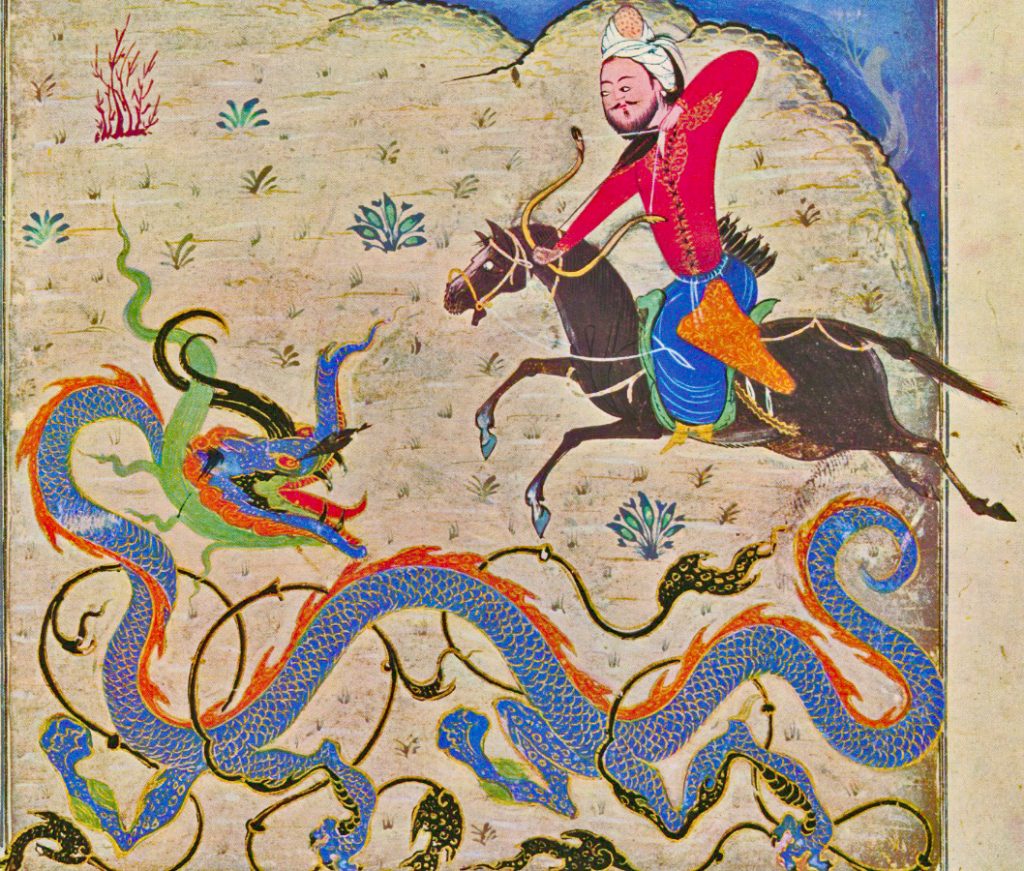

It is through Ahl Haqq traditions that the ancient Zardeh stronghold is attributed to Sasanian King Yazdigird III. First of all, it is important to stress that ancient archaeological sites in Iran (and elsewhere in the Middle East) with standing ruins from the past are often associated in local legend with a heroic figure. Thus we have Qal‘eh-i Zohāk (the castle of a mythical Persian king), Masjed-i Suleimān and Takht-i Suleimān (the ‘Mosque and Palace Terrace of King Solomon’), and Qal‘eh-i Dukhtār (a sort of generic ‘Castle of the Princess’). The site of the famous rock reliefs of the Sasanian kings near ancient Persepolis is called locally Naqsh-i Rustam ‘Rustam’s Picture’ – an allusion to the heroic figure of Firdowsī’s national Persian epic the Shāhnāmeh (the ‘Book of Kings’). Heroes were frequently painted in combat with dragons.

But references to historical figures (rather than mythological) are rare. So can King Yazdigird be credited with building the formidable stronghold of the Zardeh tableland?

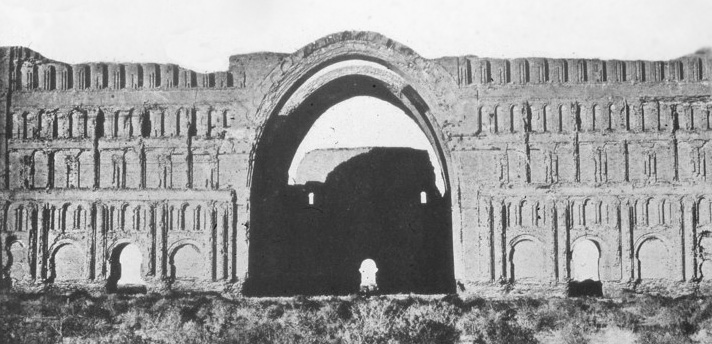

The first reality is that on the battlefield of al-Qadasīyyah, in mid-central Iraq, around the year 15 of the Islamic era (AH 15/35 CE) King Yazdigird’s forces (unexpectedly in Sasanian eyes) failed to stem the advance of the Arab forces of Islam. The subsequent equally unexpected failure of the Sasanian army to withstand the Arab attack on the capital of Ctesiphon – at the battle of al-Madā’in, in 16AH/CE 36, laid the kiss of death upon the dying Sasanian regime in Iran. The King of Kings fled, leaving many of the royal treasures behind, much to the amazement of the Arab conquerors who had never seen such opulence before.

A final Iranian stand against the Arabs on the plains of Mesopotamia was made essentially near what is the modern border between Iraq and Iran, at the battle of al-Jalūla. Here again the Arabs were successful, and Yazdigird’s forces met their final defeat at Nihāvand, on the Iranian plateau, in CE 641. In reality, there are actually no precise calendar dates recorded for when these battles occurred. But the time lapse between the initial debacle at al-Qadisīyyah and the penultimate defeat at al-Jalūla is likely no more than three to four years. The defences of the Bān Zardeh tableland would have needed several years for them to have been completed. There is no way that their erection could have occurred during the frantic, sudden unplanned flight of Yazdigird from his capital.

The Yazdigird connection with the ruins of Ban Zardeh

Endorsing the notion, however, of the name of Yazdigirdin connection with the archaeological ruins of the Zardeh tableland is the remarkable existence of a rock-carved inscription at the side of the Rījāb river where it debouches from the mountains, some 12 km south-east of Bān Zardeh (Jalili & Golzari 1978:108)

The inscription announces a dedication made in AH933/1526 CE by shaykh ‘Amīr Qumām al-Dīn of Zohāb in the form of land and properties as financial support for the operation of the Bābā Yādgār shrine. The donation was motivated by the fact that, while the shaykh was imprisoned in Baghdad, Bābā Yādgār appeared to him in a dream prophesying his release. On being asked who he was, the apparition revealed that he was Bābā Yādgār and his home was Sarā-y Zard Yazdigīrdī (“Yazdigird’s Yellow Seraglio”). The connection of ‘Zard’ (“yellow”) with the village name of Bān Zardeh can be explained by the fact that – in the Ahl Haqq faith – there is the belief that ‘good’ people are made of yellow clay, ‘bad’ people of black mud.

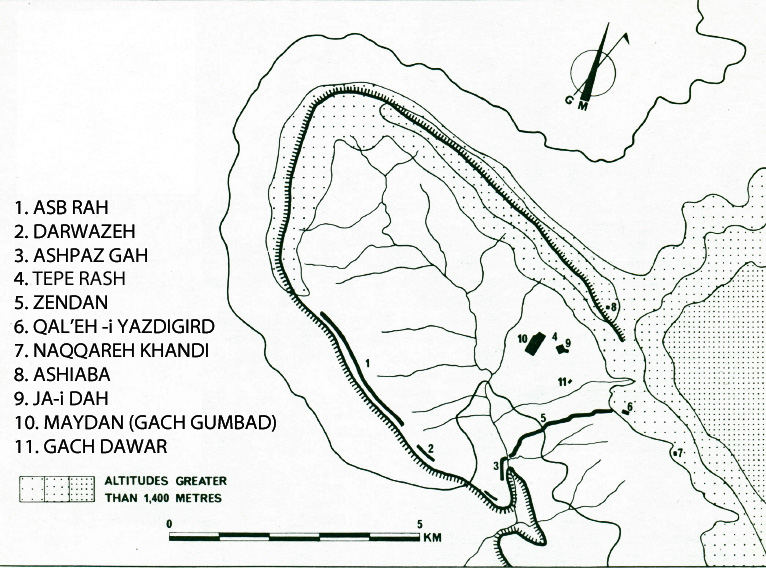

Besides this 16th century dedicatory attribution, legendary connections to King Yazdigird are firmly fixed in the minds of the Ahl Haqq on the landscape of the Zardeh tableland, in the form of toponyms derived from associations with presumed activities of the Persian king.

Thus we have his seat of enthronement: Shāh Neshīn (“Seated King”); Qal‘eh-i Yazdigird (his “Castle”; Maydān (“Parade Ground”); Zendān (“Prison”); Āshpaz Gāh (“Kitchen”) ; Naqqāreh Kāaneh (“Trumpet House”); Āshiābā (“Windmill”); and Bībī Shahrbānou (Yazdigird’s daughter). It is this last feature that best allows us to deduce the connection between the archaeological sites and the legends.

Bībī Shahrbānou was the daughter of Sasanian King Yazdigird III. According to Iranian tradition, after the Islamic conquest she married Hussayn, a grandson of the Prophet Muhammad. As such, many Iranians take pride in the fact that, in their eyes, the religion of Islam was not exclusively that of the Arabs. This positioning may well have gained prominence in the area under our scrutiny as a result of Sultān’s Ishāq’s formulation of the Ahl Haqq creed. This phenomenon of the accentuation of a Persian connection to Arab Islam is well attested elsewhere in Iranian traditions.

For further reading see: