Introduction

A large corpus of decorative stuccoes once adorned the walls of the palatial garden pavilion whose remnants are still preserved in the field of Gach Gumbad. There is ample evidence that this ornament was once embellished with a polychrome paint scheme. But, at the moment, not enough of the stuccoes have been unearthed to give us a complete indication of the overall decorative scheme in the various halls of the pavilion. But while only a small portion of the ground plan of these halls has been delineated, and only a small sondage in one of them (GG#1) excavated down to an original floor level, they have already furnished a rich inventory of lavish building ornament.

With the exception of one tiny sounding dug in 1965 down to an original floor – roughly four metres below the level of the ploughed field – all of the stuccoes exposed so far are either decorative features still intact upon standing walls, or pieces of ornament from the top 2.5 metres thick stratum of collapsed building debris that has fallen down into rooms. The bottom 1.5 metres thick stratum of this collapsed debris is largely unexplored. The absence of this data is particularly significant in terms of the potential for determining the original decorative schemes, because the lowest strata are likely to reveal the most about how the rooms were roofed (flat roof versus masonry vault: see Link #3).

The untapped repository of stuccoes that still lie in the ground in the bottom two-thirds of the collapsed building debris of the Gach Gumbad palatial complex, underlines the fact that the site of Qal‘eh-i Yazdigird represents arguably one of the richest storehouse of Parthian architectural ornament ever unearthed. The inventory presented here is aimed at feeding the imagination of students who may wish to study different aspects of Parthian art, as well as to encourage the Iranian authorities to take up the initiative and put the site on the world stage where it belongs, by continuing an excavation program.

The inventory is presented with three perspectives in mind. The first is to document, if possible, where the decorations were first applied – in other words, their original provenance (not their excavated context). The second perspective is to classify what kind of role the architectural ornament reflected in an excavated piece. In other words, items like capitals and engaged columns are featured, as a way of looking at what part they played in the overall decorative scheme. The third perspective looks at the iconographic themes – in other words, what subjects were being presented. These subjects range from human portrait busts, to sculptured mythological scenes, to stylized ‘overall’ patterns and vertical registers.

Stylistically, the decorative elements are an eclectic mix derived from the artistic vocabularies of both the East and the West. For instance, the motif of a naked Aphrodite figure holding the tails of two dolphins is incontrovertibly Graeco-Roman in origin; the man in a tunic and wearing a pointed hat is incontrovertibly Central Asian (Scythian).

Significantly, recovered from the debris fallen down into a room, was an engaged capital. The iconographic device used to decorate the capital face consisted of a pair of inter-twined winged beasts. The artistic sense is remarkably commensurate with the kind of imagery seen in the glyptic art of ancient Mesopotamia.

But apart from this iconographic significance, the capital is important as it helps underline the fact that all of the architectural elements found in the stucco decorations are actually ‘architectonic’ – that is, they are purely decorative features, having no structural support role to play. All of these elements, whether capitals or columns, are ‘engaged’ – that is, they were attached to wall surfaces; none of them were originally free-standing.

Although the corpus is far from complete, enough has been recovered to characterize the decorations as largely secular in nature. Although some of the iconography is mythological, liturgical religious elements seem to be entirely absent. The eclectic mix makes sense best as decorations commissioned by a person of wealth, who could afford such lavish artwork, but without any deep meaning other than to impart grandiosity. The general impression one gets is that the decorations fit well with the concept of an audience hall set within a paradise garden. The portrait heads, in fact, may well represent the palace’s original sponsor.

Two other commentators have proposed even slightly later dates for the artwork than I have, namely late 2nd century CE, or even early 3rd century (see Kröger 1982; Mathiesen 1992). Both of these writers however were basing their analysis purely on stylistic grounds, as though they were dealing with isolated objects housed in a museum collection. Neither of the authors suggested any other explanation for the sponsorship of the artwork in the context of the known historical realities. This, by contrast, has played a major role in my own attempt to interpret the phenomenon of lavish decorations set within the confines of a formidably fortified stronghold in the second century. There is no reason why we cannot accept the idea of a warlord in the area right up to the time of the Sasanian conquest of Parthian Iran. Also, with the new evidence of a Sasanian fire-temple, we can be open to the idea of a remodeling of the pavilion in that era, rather than an abrupt termination of site activity at the end of the Parthian period.

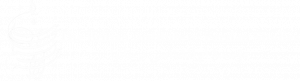

Find Spots of the Stuccoes

The find spots of the largest quantity of recovered stuccoes were the three large halls of Gach Gumbad (GG#1, #5 & #11), separated from one another by circumambulatory corridors. None of the three halls were excavated anywhere near their entirety, despite the renewed efforts of the Iranian Heritage Organization to explore them further in the 2008 season of work. Limits to that initiative were imposed by the reality that extensive exposure of the halls would have necessitated a lengthy and expensive building conservation program, even one that included constructing a protective roof covering. This writer acknowledges that total exposure of the decorated pavilion would necessitate an enormous budget and years of conservation work on the plaster decorations, as well as stabilization and weather-proofing, including roofing over the exposed remains.

The bulk of the plaster decorations excavated so far consist of ornament applied for the most part either to the vertical, interior surfaces of rooms or the zone of friezes and figural statuary set immediately below the ceiling. Many pieces were recovered from within the confines of the rooms, but high up in the collapsed building debris, implying that they had fallen from the ceiling vault or a zone close to it. Excavation of these pieces began at roughly 4 metres above the floor (for the excavated masonry walls, see Link #3).

Space GG#11 purports to be a monumental eyvān ‘large vaulted hall’ that faced out onto a gardened enclosure and potentially was once lavishly ornamented. It likely also was once embellished by the presence of an articulated façade on the exterior wall that faced the garden, in the manner of the Parthian palace at Ashur. The layout arrangement of the interior halls also seems to echo those at Ashur, further strengthening this hypothesis. But only a tiny portion of this eyvān hall has been unearthed, and no effort extended to locate the presence of such a façade. The circumambulatory corridors (GG#2&15; #3,4 &14; #12; #21) may once have carried flat wall paint. Any relief decoration recovered from those spaces is likely to have fallen in there from an adjacent monumental hall.

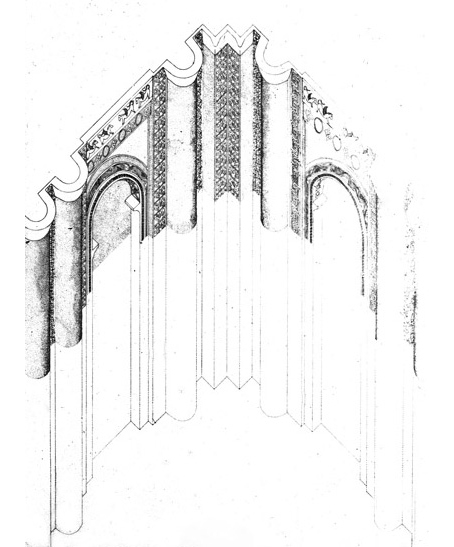

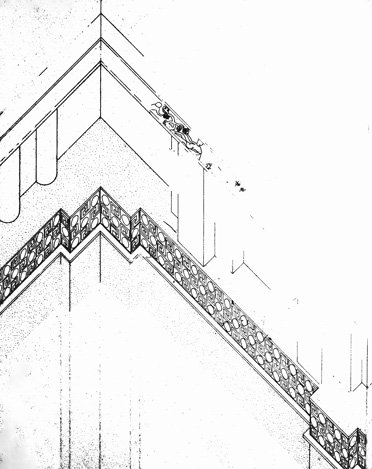

The only exception to the rule about the recovered stuccoes being from the interior of rooms applies in the case of the Gach Gumbad tower-block (feature GG#100). The original façade of the tower block was articulated, with vertical shafts of decoration. Part of that original design is still discernible at the side of a cleft in the massif that represents the junction between the original tower and a massive addition. The decorative scheme involved vertical registers of repeat designs. Seemingly, the addition that encased it was constructed following damage to the original block, likely due to an earthquake. There is no evidence to point to the possibility of this addition being due to repair and remodeling in the Sasanian era, but nothing to negate that possibility either.

Fragments of decoration from the original articulated scheme of the tower-block were recovered from where they had been deliberately dumped into ruined cloister GG#201, whose vaults had collapsed in the same disaster. This judgement is made possible by the fact that one of the pieces recovered from the cloister dump was part of a ‘peopled vine-scroll’ that is still observable in situ, inside the cleft of the tower-block. Outside of the Maydān enclosure, the Hushtāreh dump site also contained pieces of decorative ornament, likely cleared from the pavilion during the same disaster.

Physical material of the stuccoes

The Qal‘eh-i Yazdigird stuccoes were produced by quarrying and smelting locally available evaporate mineral gypsum. Heat supplied in the form of fuel burnt in a kiln drives off the water content and breaks down its mineral structure, resulting in the production of a calcium sulfate dehydrate powder. This powder can be converted into a solid plaster cement through hydration (the addition of water). After hardening, gypsum cement does not readily dissolve if it comes into contact with moisture again, making it suitable for both masonry mortar or stucco plaster. With the help of the Zardeh villagers, from experiments conducted by the Canadian team it was found that roughly two parts of hard-wood lumber were needed to produce one part of gypsum powder. The process is infinitely repeatable. In fact, the reason that the Parthian stuccoes were excavated in a field called Gach Gumbad ‘Plaster Dome’ is due to the fact that – before 1965, the villagers were in the habit of excavating the ancient stuccoes to smelt them down for plaster repairs to the Bābā Yādgār shrine dome (see images in Link #2).

The decorative stuccoes were produced using either a shallow carving technique, in the case of overall geometric ornament, or moulded in high relief (but ‘engaged’, i.e. flat back attached to a wall surface) in the case of figural pieces. The moulded stuccoes were pre-formed and then set in place as separate pieces. For the final finish, a fine plaster coat was applied as a base to carry the paint. As excavations in 1976 proceeded lower into the matrix of the collapsed masonry in GG#5, increasingly more and more traces of paint were observed on decorated pieces. This can be explained by the fact that stuccoes recovered from lower down in the trench had fallen from the walls at an earlier date; the pieces recovered from higher up had been exposed to the elements for a longer time, and the paint had faded away. Although some pieces had been protected from weathering by being buried in the fallen debris, in some cases the paint was leached out because of the damp ground conditions. Conversely, often the best preservation of paint occurred where thick encrustations had formed on the fallen pieces, due to the migration of salts in the damp ground. In these cases, sometimes it was not even obvious that a piece was actually decorated. To remove the encrustation necessitated considerable conservation work to expose the original decorated surface, usually involving hours of mechanical chipping with a hammer and fine chisel. Similar encrustation was also found in the case of the stuccoes recovered from the dumps of architectural debris cleared from damaged rooms.

A few pieces had been deliberately plastered over in antiquity, to obliterate the original design. The reason behind this decorative scheme change is not clear. No evidence was recorded of a new design executed upon this newly applied surface. Various paint colours have recently been identified by authors Khanmoradi and Niknami (2017), based on technical analysis performed on the stuccoes unearthed by the Iranian Heritage team of 2007. The main colours identified comprise red and yellow ochres (hematite and goethite based), Egyptian blue (a copper-based composition) and terre-verte (a glauconite green-earth).

Ornamental Schemes and Decorative Themes

As outlined earlier, the decorative stuccoes are presented here from two perspectives – firstly, for what picture we can reconstruct of the role they played in the decorative schemes applied in each of the three halls and on the façade of the tower-block; and, secondly, for the iconographic themes that can be identified.

Positioning of the ornament

In attempting this evaluation, the stuccoes have been grouped into broad categories, encompassing, for instance:

1.‘entablature’ (meaning the uppermost decorated zone of a wall, below its ceiling) – with subdivisions of ‘cornice’, ‘frieze’, ‘gallery’, and so forth.

2.‘engaged columns and pilasters’ (pre-supposing that, by definition, their role was non-structural) – with subdivisions of ‘shaft’ and ‘capital’.

3.‘vertical shafts and linear bands’.

4. ‘overall panelling’.

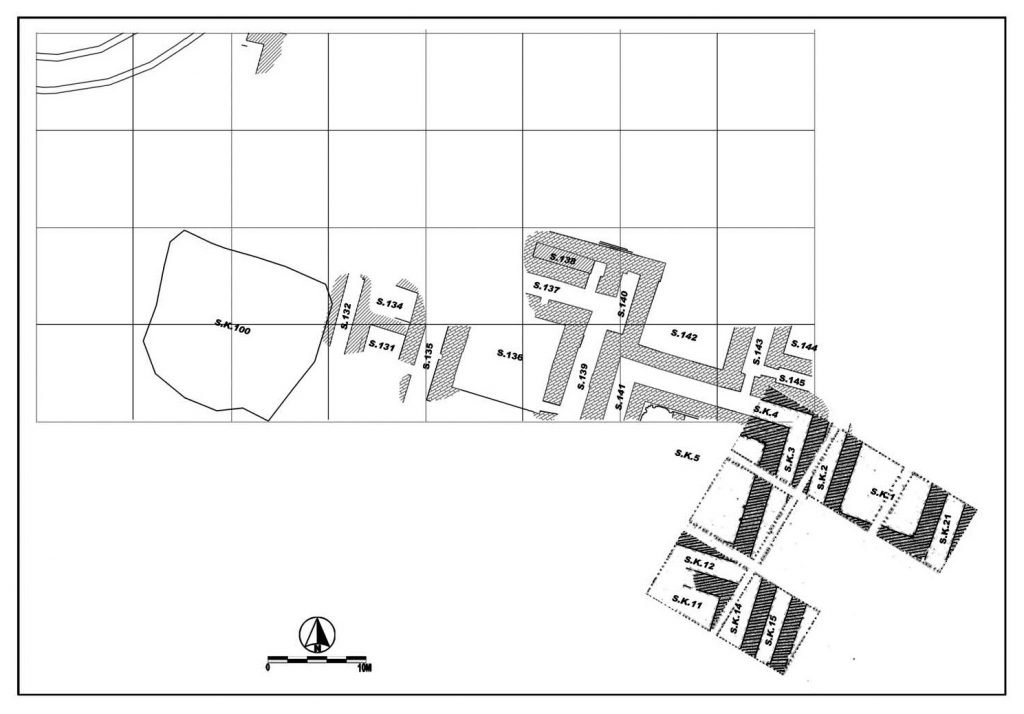

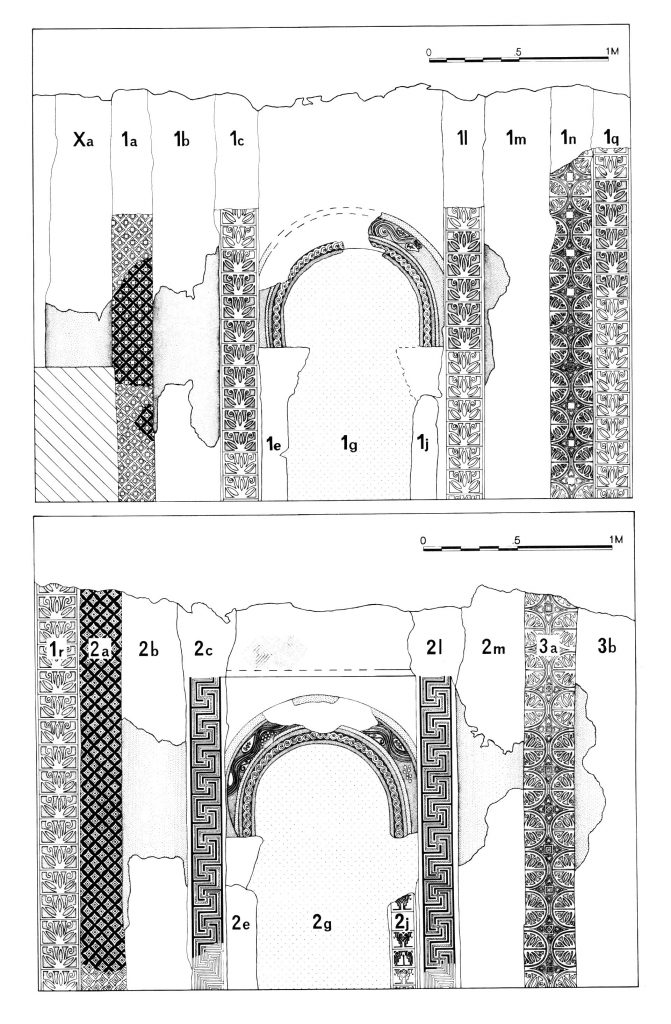

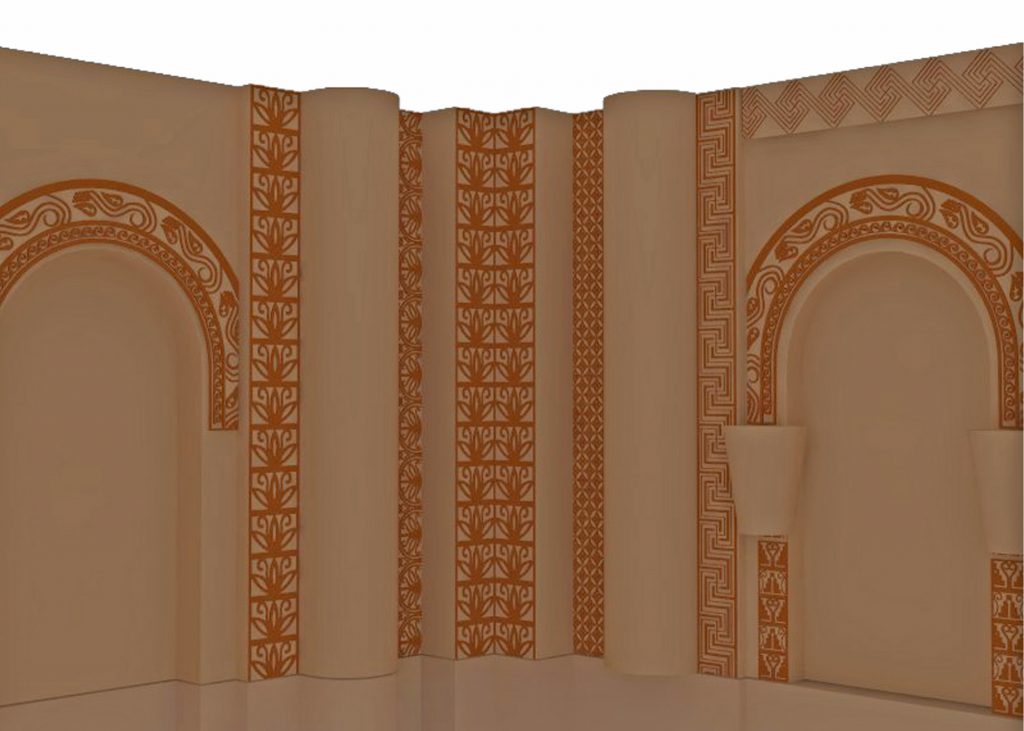

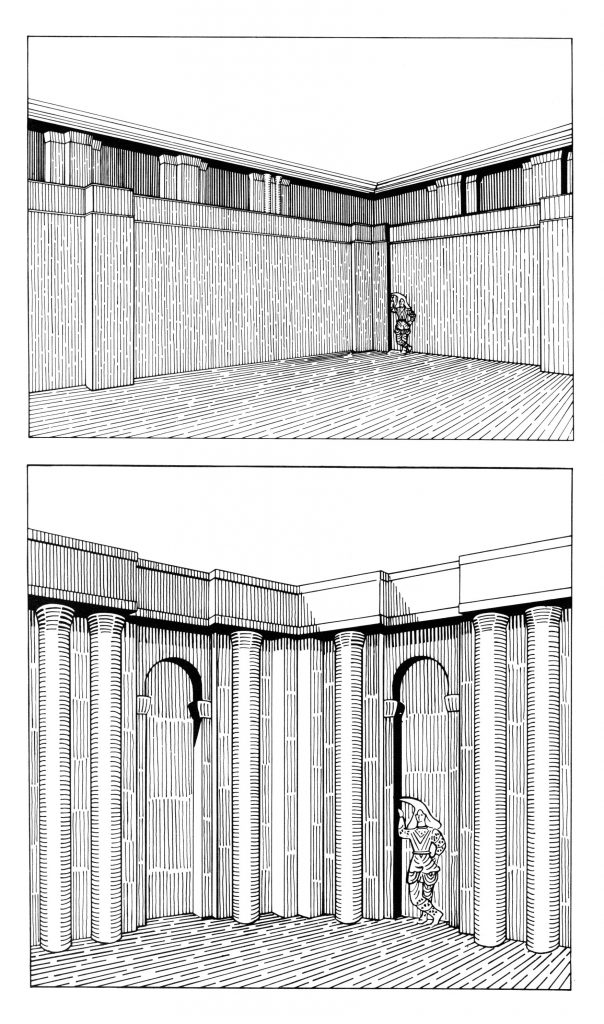

The ornamental schemes of rooms GG#1 and GG#5 are completely different from one another in compositional concept. The scheme of room 5 is dominated by the use of shallow niches that are arched and framed by rabetted jambs (‘facetted’ shafts). Each shaft carries a decorative device that consists of either vertical registers with repeat stylized designs (such as the ‘crenellation-and-vase’ or ‘bud-and-tendril’ motifs); a running series of repeated geometric designs (such as the ‘interlocking circle’ motif); or an overall ‘lozenge diaper’ pattern. Although the composite designs on the shafts are made up from simple elements, the overall effect on the wall is of an enormously rich texture, as though draped in textiles. Fallen down into the room alongside the niches – from a height as least as high as the top of their arches – were recovered stuccoes depicting mythological narrative (such as the ‘gryphon procession’), an entirely different design concept than of that below. The undersides of both the arched pieces and the niche horizontal top frames were coffered.

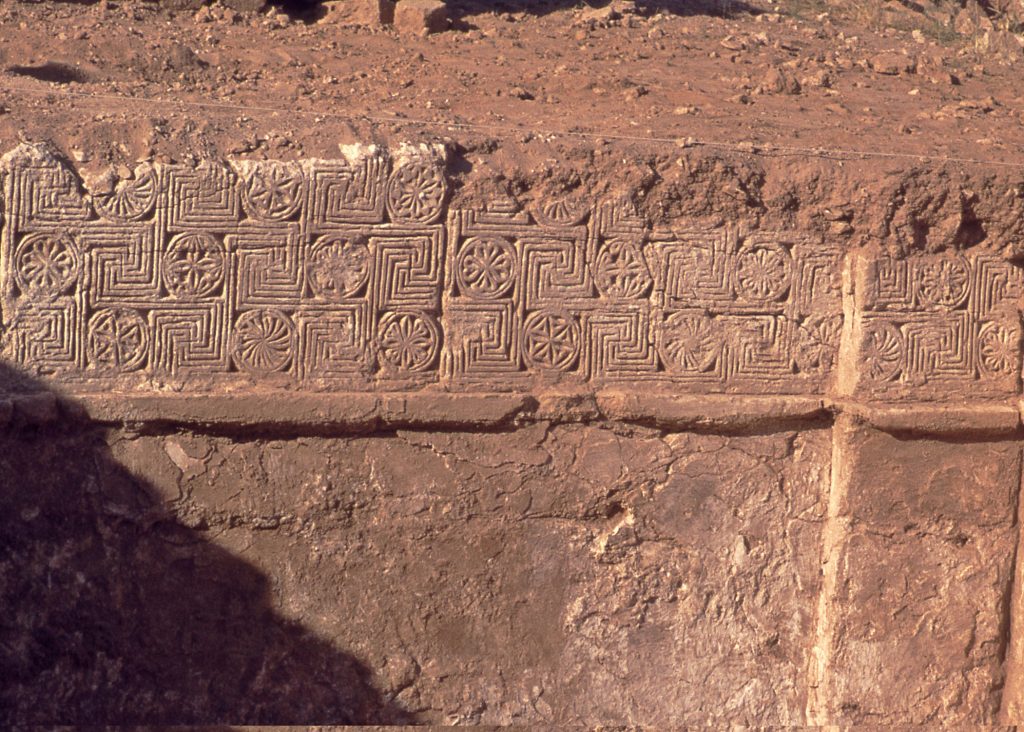

In room GG#1, the wall surfaces of the lower part of the room appear to have been plain flat. One cannot discount the possibility of them having been once painted. Unfortunately, not enough of the surface has been exposed and scrutinized closely to make this observation feasible. In the upper part of the wall a continuous panel ran the full length of both walls that were exposed. The panel carried a repetitive design of shallowly carved devices, comprising an interlocking ‘Greek-key’ pattern, interspersed with abstract motifs set in roundels.

The moulded edging at the top of the running panel was sufficiently preserved to reveal a setback articulated by a row of colonettes, a tantalizing glimpse of the fact that the entablature zone below the ceiling was richly ornamented. Small anthropomorphic statuettes (such as the ‘hypnos’ cupids), repeat reliefs of mythological creatures (such as the ‘gryphon–senmurv’), and framed human portrait busts were part of this below-the-ceiling zone of decoration. Fragments of coffered cornice-work can be judged to have once surmounted this zone.

Decorative Style and Motifs

The subject matter of the decorative stuccoes is an eclectic mix, including stylized abstract devices, portrait busts, mythological creatures, and narrative scenes. As stated in the introduction, the motif of a naked female holding the tails of two dolphins (attributes of the Greek goddess Aphrodite) is incontrovertibly Graeco-Roman in inspiration; the male figure wearing ‘shalwar’ pantaloons, tunic top, and a pointed ‘Scythian’ cap is incontrovertibly Iranian in inspiration; the inter-twined winged beasts are reminiscent of mythological scenes on seal-stones and so forth from ancient Mesopotamia. Other design elements in the stucco inventory include narrow bands of relief moulded repeat ornament (such as a running vine scroll) and shallowly carved overall decorated paneling, consisting of both diaper patterns and interlocking geometric devices. The stylized motifs are often presented in vertical registers; sometimes the repeat designs are presented in linear, horizontal running bands.

The ‘free-form’ sculptural anthropomorphic, mythological figures are derived from a western Graeco-Roman tradition of artistic representation of human form. But the presentation of human busts set within medallion frames helps mark out significantly how much ‘Iranian element’ concept there is in the Qal‘eh-i Yazdigird stucco inventory. There is no attempt, as there was in ancient Greek art, to portray a human face with an artificial, idealized sense of perfect beauty. They are literally portrait pictures, captured in a static frontal pose. They are as expressionless as our today’s passport pictures. Yet they do not reflect an ancient Near Eastern tradition (e.g. Hittite, Assyrian, Babylonian) which favours a more flat rendering, mostly presenting the human figure in profile, not in a frontal stance.

The flat, frontal pose principle is prevalent in many of the sculptural statues of royal dignitaries unearthed at Parthian Hatra. In royal Parthian coins, too, kings were portrayed with their personal traits, warts and all; none of the idealized beauty of the Alexandrian coin portraits that glossed over the conquering warrior’s numerous combat scars. While a western attitude would scorn the stiff rendering of the human form, the eastern tradition focusses on personal status – dress ornament and personal jewellery are more important than facial expression.

Equally, in contrast to the western tradition for the artistic representation of natural vegetation, vegetal motifs in the Qal‘eh-i Yazdigird stucco inventory are presented in an eastern style. Instead of the classic western attempt to represent natural vegetation accurately, in its botanical sense, the eastern tradition is to represent it stylistically. Such artistic renderings are quite likely to be derived from weaving traditions. The ethnic origins of the Parthians lie in the nomadic steppes of Central Asia. Their dwellings were likely goat-hair tents or woolen felt yurts. Furnishings for these dwellings likely included hung woven fabrics. Flat-loom weaving lends itself easily to the reproduction of designs in a ‘geometric’ fashion; natural vegetation thus gets reproduced as a stylized design. Fabric woven patterns could have easily been transferred to plaster ornament when it came to decorating the walls of masonry built structures.

In keeping with this sense of plaster wall decorations reflected in a past woven fabric wall-hanging tradition, one may refer to the observation that many of the stylized Qal‘eh-i Yazdigird motifs are repetitive – academically they are referred to as ‘overall’ designs, a little bit like our old-fashioned wall-paper.

An element that is quite sophisticated in the stylized Qal‘eh-i Yazdigird vegetal designs is when the motifs are split into two, and the halves placed back-to-back. Thus, natural vegetation has been first stylized and now geometricized. By taking a circle containing a ‘bud-and-tendril’ motif and splitting it in half – the half circles now back-to-back – the artist has essentially paved the way for the development of the Islamic ‘arabesque’, where the portrayal of a vegetal motif no longer matches the vegetation as it occurs in nature.

What to extract from all these principles? The Qal‘eh-i Yazdigird stuccoes are a treasure-trove of Iranian art. In themselves, overall, they are an eclectic mix, best seen as decorations chosen to ornament the walls of a ‘nouveau riche’ warlord’s lavish domain in the late Parthian era. They also point to the future evolution of Sasanian and later Iranian Islamic art.

For further reading see:

Keall 1989a; 1989b; 1982; 1976b

Kröger 1982