The Tableland

In reality, the entire archaeological site is comprised of an elevated tableland covering some twenty-five square kilometres, on the extreme edge of the Zagros mountains close to Iran’s border with Iraq.

For convenience, the entire archaeological site has always been reported under the rubric of Qal‘eh-i Yazdigird (“Castle of King Yazdigird”), following a local tradition. However, technically this descriptive label should only have been applied to a pinnacle-top fort that overlooks the tableland. A better descriptive would have been Serā-y Zard Yazdigīrdī (see Link #6 for an explanation of this point). But this rubric was unknown to Keall at the time of his first exploration of the Zardeh tableland. Since the site has for years been published extensively as Qal‘eh-i Yazdigird, this rubric is retained here.

Approaching the Zagros from the plains of Mesopotamia to the west the Zardeh tableland forms the last ledge of the high mountain range. Seen from near the main Iraq-Iran highway the tableland looms up as though free-standing.

4, 5 & 6. The Zardeh tableland at the extreme western edge of the Zagros.

But although there is a formidable escarpment, the tableland is adjoined at one end to the main body of the high Zagros mountain range towards the East. Here, a moderately gentle pass, known historically as the ‘Zagros Gates’ (and marked by the stone arch monument of Tāq-i Gīrrāh), provides relatively easy access from the plains of Mesopotamia onto the higher reaches of the Iranian plateau. This ease of into Iran from explains why this route has been so attractive to travelers for centuries, even till to-day.

Seen from above, the tableland is a thumb-shaped projection, the terminal end of the syncline vale that is the last ledge before the ground drops away to the plains of Mesopotamia. Two-thirds of the tableland is free standing, with a precipitous escarpment overlooking the plains below to the west and north. The tableland has a basin top where habitation was possible. On its northeastern side, the tableland rises up in the form of cliffs that merge with the higher massif behind.

8, 9 &10. The basin topped tableland and the steep cliffs behind the village of Zardeh.

Easy access to the tableland was only across the open neck of land that connects the tableland to the pass of the Zagros Gates. It was across this neck of land that formidable defensive fortifications were erected, though fortifications were also built around the entire tableland wherever it was perceived the escarpment did not provide adequate natural defences.

Perimeter Fortifications

Impressive fortifications surround the 25 square kilometre area of the tableland. As just described, the most massive of the fortifications was the defensive wall thrown across the neck of the tableland. This defensive wall ran for nearly three kilometres from the escarpment to the cliffs. The wall was fortified at regular intervals with towers. The massive character of these defences was clearly designed to repel attacks from the easiest point of access onto the tableland, and which coincidentally also led from the Zagros Gates. One may perceive this as the direction from which the tableland was most easily threatened, attested by the numerous arrow embrasures along its length.

11 & 12. Long defensive wall running from the upper cliffs to the escarpment; arrow embrasures.

At the lower end of the long defensive wall, its effectiveness was reinforced by the presence of a block-house, locally called Āshpaz Gāh (“Kitchen Place”). This rectangular guard post was positioned close to where the track from Tāq-i Gīrrāh enters the heart of the tableland.

At its upper end, the long defensive wall culminated at the cliffs, above which the isolated upper pinnacle fort – the real Qal‘eh-i Yazdigīrd – served as a major guard post for entry into the tableland from the high ground. It is likely that the rounded towers of the Upper Castle, which were erroneously taken by this writer in 1965 as a clue to a Sasanian date for the site as a whole, are in fact a reflection of modifications made to the Parthian-era fort in Umayyad times. As it turns out, elsewhere on the tableland, the towers of the Parthian era defensive walls were square, as documented clearly in the Zendān (“Prison”) section of the defences. An Umayyad parallel for the rounded towers of the Upper Castle is well exemplified in those of the castle of Puskān in Fars province (Vanden Berghe 1990).

14. & 15. The Upper Castle’s commanding view over the tableland.

Flanking the upper fort in Parthian times, on cliff-top pinnacles, were two strategic defensive points with a view across the tableland down to the plains belowThese defensive posts – Āshiabā (“Windmill”) and Naqqāreh Khāneh (“Trumpet House”) – complemented the role of the pinnacle fort, both as look-out positions, as well as protection against unwanted entry onto the tableland by way of the stream-carved gorge of Bābā Yādgār.

By comparison with the scale of the fortifications in the lower reaches of the tableland one can judge that the occupants of the stronghold must have had a good relationship with the residents of the Dalahū highlands. The tableland was fairly easily approached from the upland side by attackers having a familiarity with the rocky mountainous terrain, and there are traces of defensive walling in this upland zone behind the cliffs. But by far the greatest effort to defend the tableland was directed towards approaches made on its southern and western perimeters.

The high ground offers a commanding view across the entire tableland. A formidable escarpment rings the tableland.

Mention has been made of the Āshpaz Gāh guardhouse. Besides controlling access to the tableland from the east, it also served to monitor the natural path that climbs the escarpment at this point. Tribesmen drive their flocks and baggage animals up this path on their annual migration to the upland pastures of Dalahū and before the building of the bridge at Rijāb, the men of Bān Zardeh frequently traveled this path on their way to market in Sar Pūl.

So, although formidable, the escarpment needed surveillance. Fortifications were erected at the rim of the tableland wherever the architects of the stronghold deemed scaling the escarpment from below was feasible. The defensive walls were punctuated with slots through which to fire arrows at attackers. Remarkably, during the brutal stand-off between Iran and Iraq in the 1980s, some of these ancient defensive walls were used as ‘blinds’ for the Iranian military to mount their gun emplacements in a move to thwart any potential attempt on the part of the Iraqis to gain the highlands of Iran.

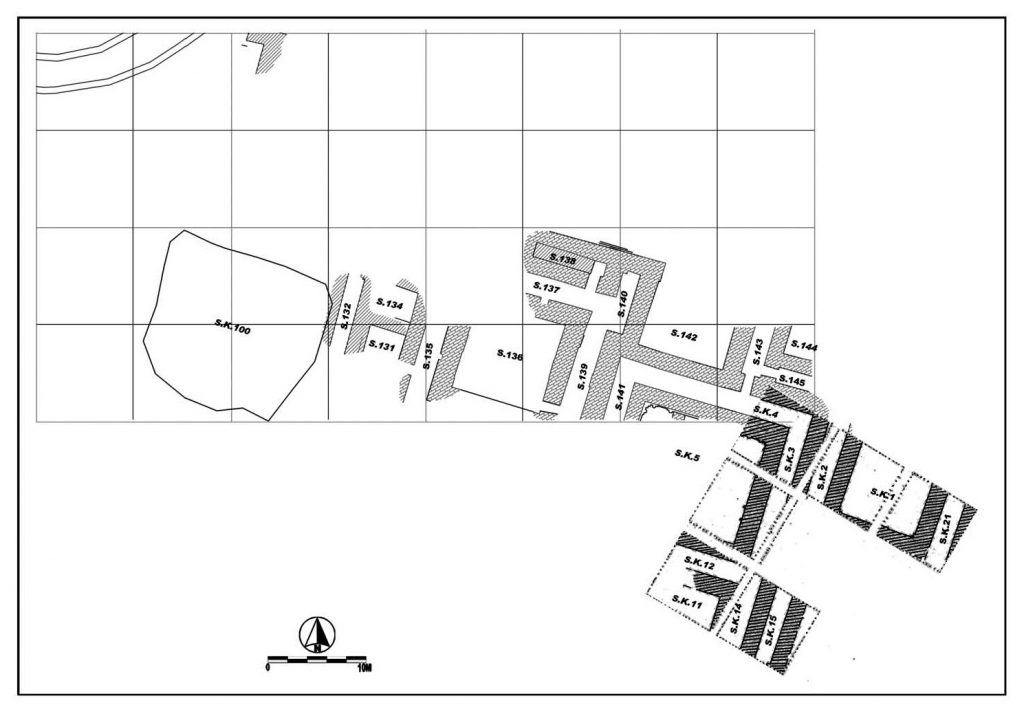

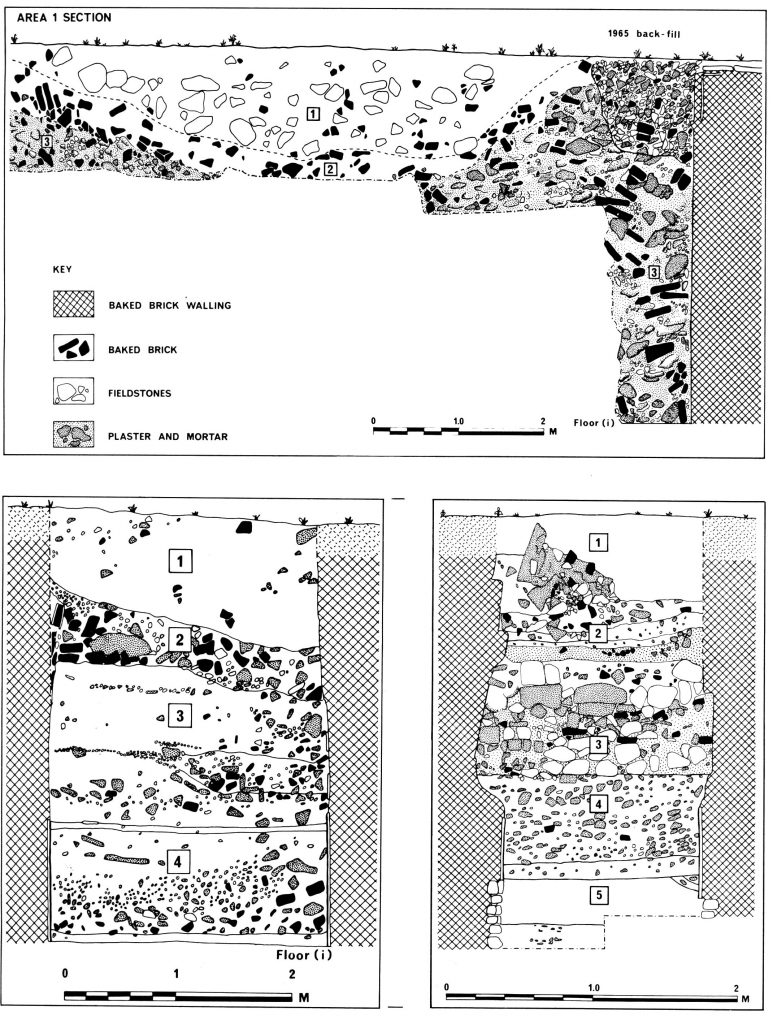

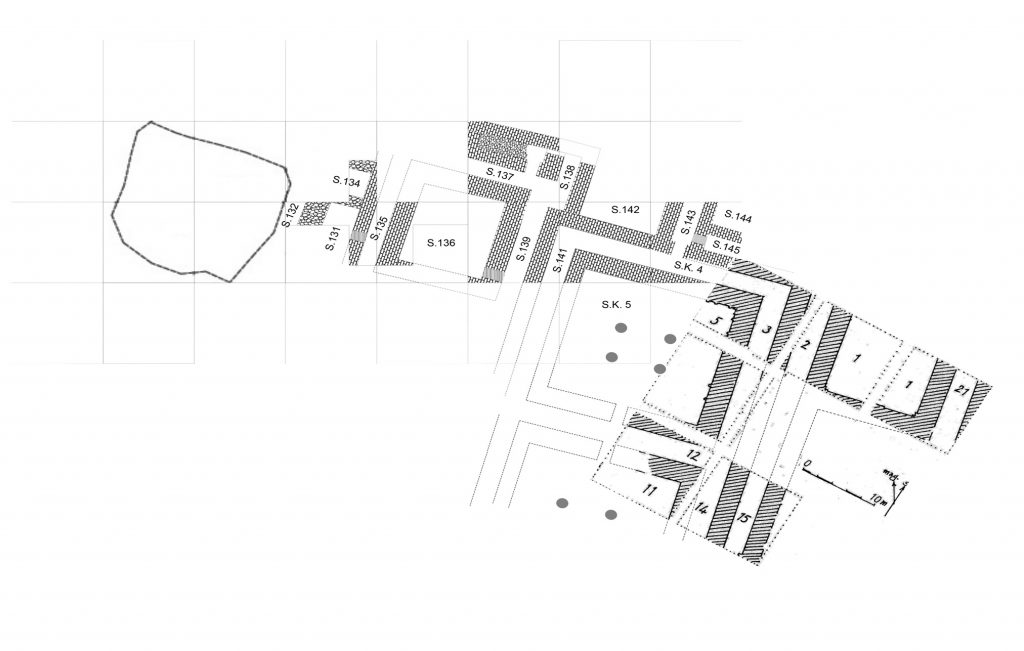

In 1975 the Canadian Mission conducted strategic soundings alongside the wall in the area known as Zendan (“Prison”). The conclusion drawn was that this occupation reflected the manning of the military defences in Parthian times. In time I was to judge that, overall, the fortifications of the tableland were designed primarily to thwartany attack from the lower reaches – that is, an attemptto storm the stronghold by state forces sent by the government from its capital base on the plains of Mesopotamia in the 2nd century CE; or, conceivably, by forces sent by some authority from Media, in the east.

24. & 25. Zendan section of the long wall; tower excavated in 1975

Heart of the Stronghold

The Zardeh tableland is not completely flat on top; rather, it is basin-like, so that the structures built there are sheltered, and the hollow of the tableland is watered by the Bābā Yādgār stream that flows from a spring fed by high mountain snow melt. The most enigmatic of the Zardeh tableland structures is the massive enclosure of Jā-y Dār (“TreePlace”).

26, 27 & 28. Walls in the orchards of Ja-y Dar below Ban Zardeh village

Its nomenclature is not derived from the Arabic word dār (“Palace”). Rather, dār is a Kurdish word meaning “tree” and reflects the fact that the ruins are almost entirely swallowed up by orchards that help sustain the lives of the villagers – and difficult to investigate as a result. Rawlinson gives no explanation for why he designates these ruins as Dīwān Khānah (“House of Administration”). One may deduce however from the impressive defences of the structure that this was the innermost fortress, or ‘keep’, of the stronghold. Whether the warlord lived there with his family on a normal basis, reserving ceremonial activities for the garden pavilion, is a matter open for debate. Certainly one can see it potentially as a strongly defensive enclosure for times of emergency, as well as a permanent base for the garrison soldiers and their riding steeds, and a secure storehouse for supplies and treasure.

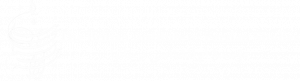

As for the Maydān gardened enclosure, set at its upper end was a palatial pavilion, adorned with lavish architectural ornament. The field where the ornamental walls were exposed is called locally Gach Gumbad (“Plaster Dome”). The walls were built of baked bricks laid on their edges, at right angles in each successive lay

Although requiring considerable conservation efforts to preserve them, if they were exposed permanently, the walls of this pavilion are remarkably preserved – to a height generally of four metres above the original floor, with decorations still intact in some places. The reason for the preservation is that when the building started to collapse, the roof seemingly fell into the void of the empty rooms and began to preserve the walls in this matrix of collapsed building debris.

The Canadian Mission of 1976 made major inroads on defining the decorated walls, along with a season of conservation of the excavated ornament in 1977. The Iranian Heritage Organization further delineated the walls of the pavilion in 2008.

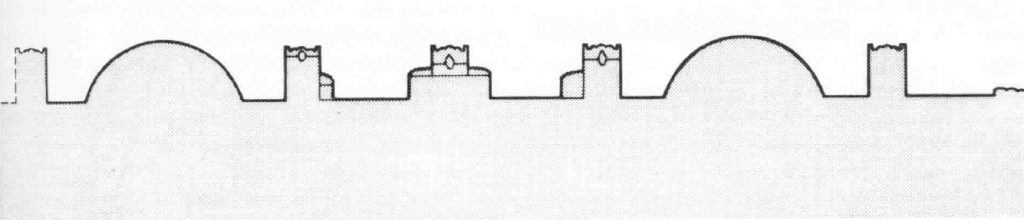

The monumental rectangular halls and their ambulatory, surrounding corridors are very reminiscent of other late Parthian palatial structures, such as those of Ashur and Nippur in Iraq. Unfortunately, not enough progress has been made in the Gach Gumbad excavations to determine what kind of roofing was involved. The circumambulatory corridors have traces of brick barrel vaulting.

But the spans for the large halls are quite considerable, and the use of barrel vaults for them, rather than flat roofing, has not yet been attested. In the Parthian period one would not expect domes. Room GG#1 (site of Gach Gumbad) is less than ten metres wide, but Room GG#5 is approximately twelve and a half metres square. Masoud Azarnoush proposed that it would have been flat-roofed with post-and-beam construction, in the manner of the great hall at Ashur. But he presented no definitive evidence for the existence of these. Incidentally, the great vaulted brick hall (‘eyvan’) of Taq-i Kisra at Ctesiphon is twice the width of rooms GG#5 & 11.

A large number of decorative stuccoes that once adorned the walls of a palatial pavilion were unearthed. As well, some ornamental fragments were recovered from heaps of architectural debris that had been dumped outside of the pavilion, in the land locally called Hushtāreh (“Thorn Bushes”), through clearance likely following earthquake damage. The area was accessed from the main pavilion by way of a small gate in the enclosure perimeter wall.

Some other stuccoes were recovered from where they had been dumped in a cloister – space GG#201 – an open arcade – that overlooked the garden.The act of dumping the debris in the cloister – which itself was damaged – filled the arcade from floor to ceiling, with no perfect sense of their original provenance.

Not enough of the surviving Gach Gumbad building has been cleared as yet to determine whether the remodeling that occurred after the destruction was executed in Parthian times, or later, in the Sasanian era. Large fragments of decorative ornament recovered from the room fill imply that the ultimate demise of the pavilion may have been due to a second incidence of earthquake destruction.

At the moment, not enough of the decorations have been unearthed to give us a clear indication of how the decorated spaces were utilized. With the exception of one tiny sounding that dug in 1965 down to the original floor of the pavilion – roughly 4 metres below the surface of the ploughed field – all of the exposed stuccoes recovered so far are either ornamental features still intact upon the standing walls, or pieces of decoration fallen down with building debris that fills the rooms, in the top third of the matrix of this fill.

The bulk of the plaster decorations excavated so far consist of ornament applied for the most part to the vertical, interior wall surfaces of rooms, especially rooms GG#1 and #11. Some of the stucco artwork is still intact upon standing walls, while many detached pieces have been recovered from within the confines of these two rooms.Excavation of these detached pieces started at roughly four metres above the floor. This implies that their original position was in a horizontal decorative zone that ran below the ceiling.

Decorative Stuccoes

The decorative stuccoes were produced using either a shallow carving technique, or moulding in high relief. The moulded stuccoes were pre-formed and then set in place as separate pieces. The stuccoes would have been painted for the final finish, following the application of a fine plaster base to create a smooth surface for painting.

The only exception about the stuccoes being wall decorations on the interior of rooms, is the fragment depicting a human head peopling a vine scroll. This ornament was originally part of the decorative scheme of an articulated tower block (space GG#100). This fragment was recovered from the cloister dump (GG#201). An identical match to the design is still preserved in situ on the face of the original Gach Gumbad tower-block, discernible in a cleft where an addition to the tower block has pulled away from the original block.

As the excavations in 1976 proceeded lower in room GG#5 into the matrix of collapsed fill, increasingly more and more traces of paint were observed on the pieces of decorated stucco, having been protected from weathering by being buried in the fallen debris. This can be explained by the fact that the pieces recovered from lower down in the trench had fallen from the wall at an earlier date; the pieces recovered from higher up had been exposed to the elements for a longer period of time, and the paint was leached away.However, burial also encouraged the migration of salts in the damp ground, often resulting in the formation of thick encrustations covering the entire plaster fragment. This necessitated considerable conservation work to expose the original decorated surfaces. The same conditions of preservation applied in the case of the fragments of ornament recovered from the dumps.

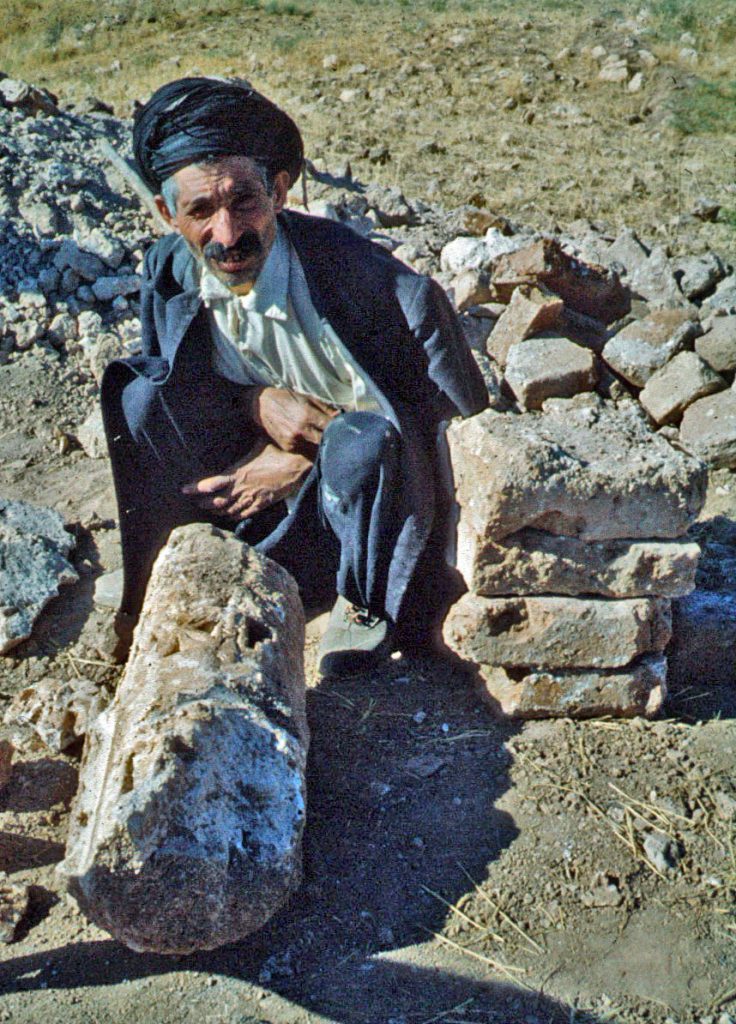

Gach Gumbad West

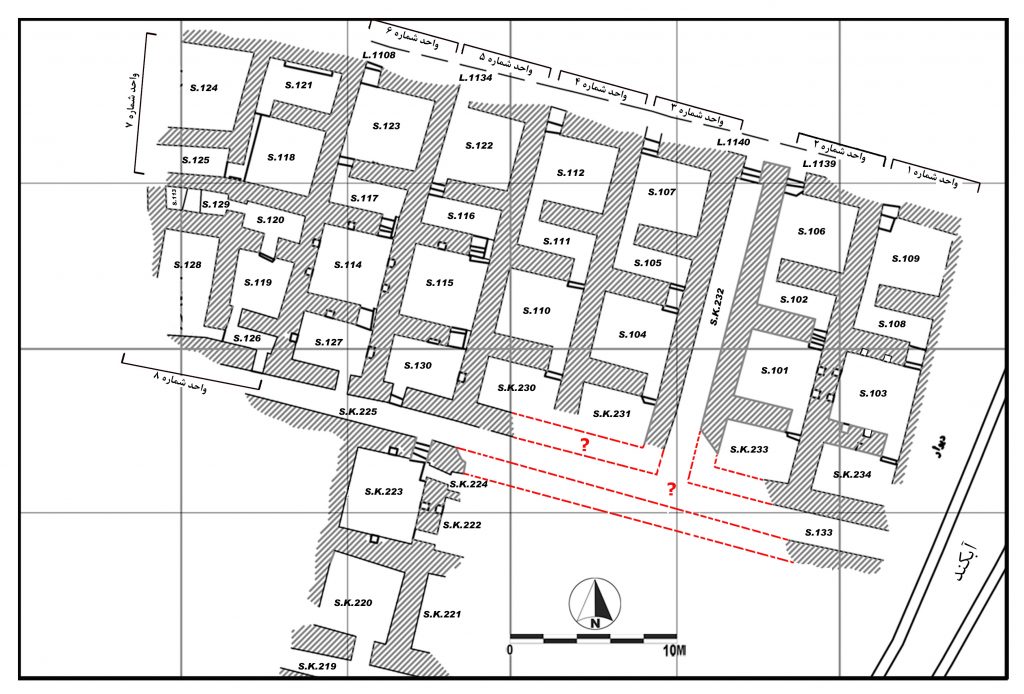

Attention was applied in 1978 to what could be seen as outlines of small rooms in the upper corner of the Maydān enclosure, an area usually referred to in the archaeological record as Gach Gumbad West (though in terms of land ownership the area is part of the Hushtāreh scrubland).The outlines of rooms were clearly visible on the ground surface when the low sun cast shadows across the spaces. A few of these rooms were excavated by the Canadian Mission, at the edge of the erosion gulley that pierces the land between the Gach Gumbad field and the north-west Maydān. Instead of baked bricks, rubble-stone and mortar masonry was used to build small rooms.

This work was expanded by Masoud Azarnoush in Gach Gumbad West on behalf of the Iranian Heritage Organization in 2007, with the exposure of an extensive series of small units. Each unit had its own oven, in a small open courtyard.

The conclusion that one can draw from the excavation report is that these units represent the living quarters of people whom we may envisage as retainers of the stronghold, and their families. There were no grandiose spaces provided that would suggest the alternative proposition that the units provided accommodation for the resident lord’s family, or visiting guests. The layout of the space was simply not grand enough for that.

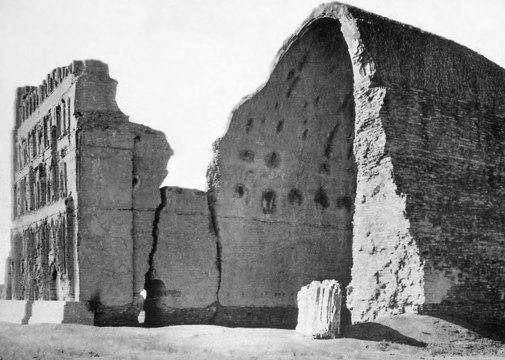

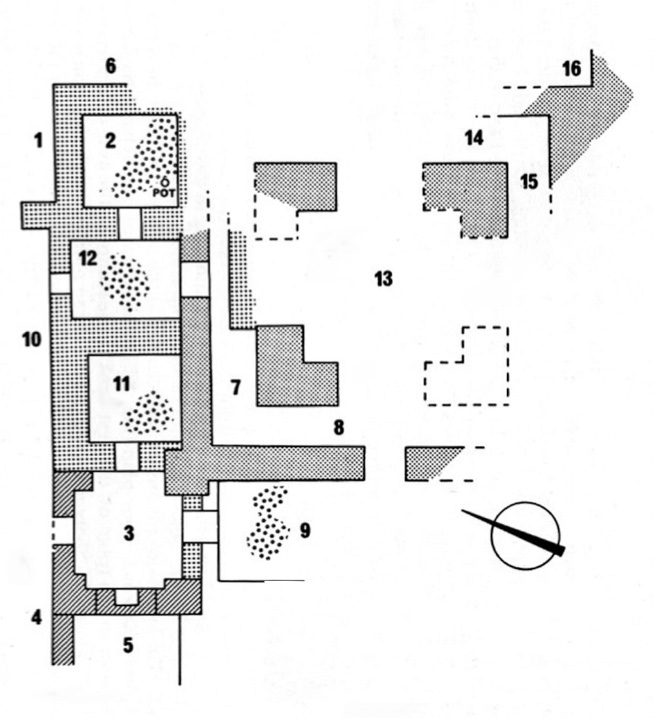

Gach Gumbad Tower Block

In front of the Gach Gumbad pavilion, but off to one side, there was a solid block of masonry. The only opening penetrating the block was a corridor that seemingly provided access to a staircase leading to the roof. It is apparent that at least one face of this tower was originally decorated with plaster ornament.

53. & 54. The Gach Gumbad Tower Block.

The proposition that all four sides were originally ornamented leads to the conceptualization that this was a monument in the vein of the victory tower of King Narses at Paikulī, in eastern Iraq. The tower does not necessarily have to reflect a definitive victory, but we may freely describe the Gach Gumbad tower as a commemorative monument. It held a significant position alongside the pavilion, at the head of the gardened enclosure, and – because of how the terrain sloped away below it – was visible from some distance.

Following the incident of severe damage to the palatial pavilion – most likely caused by an earthquake – the Gach Gumbad tower-block was reinforced by construction of a massive addition on its northeastern side. This addition is the explanation for how one of the original decorative faces was preserved, as it became embedded in the new masonry; discovery of that original decorated face was due to the fact that over time the addition pulled away from its base, with the decoration discernible in a crevice that formed between the two beds of masonry. When built, the addition was articulated on its exterior face with projecting half columns.

In light of the hitherto unexpected evidence that there had been a Sasanian presence on the Zardeh tableland after all, one should be ready to accept the idea that this addition – in response to severe damage – could have been the work of a Sasanian governor. But Parthian period work is not entirely out of the question. What is clearly apparent however, is that when the tower-block was remodeled, large numbers of decorative fragments were cleared from the damaged structure and dumped elsewhere, as with the fragments fallen from the main pavilion. Unfortunately, we have no indication as to whether the nearby brick-lined pool (GG#199), which was excavated in an earlier season and presumably part of the irrigation system for the garden, was obliterated at this point.

Zoroastrian Fire-Temple

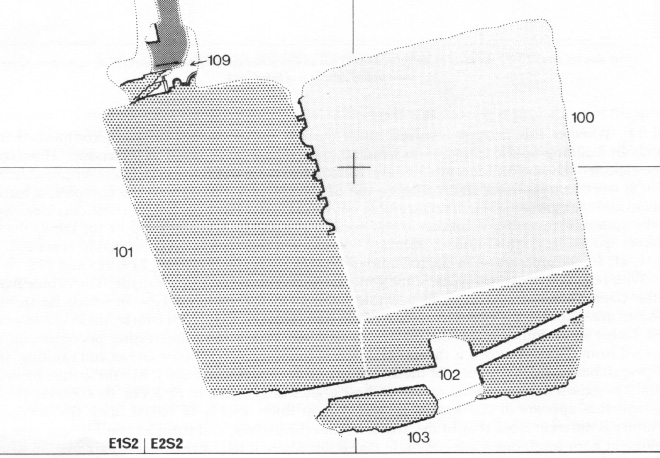

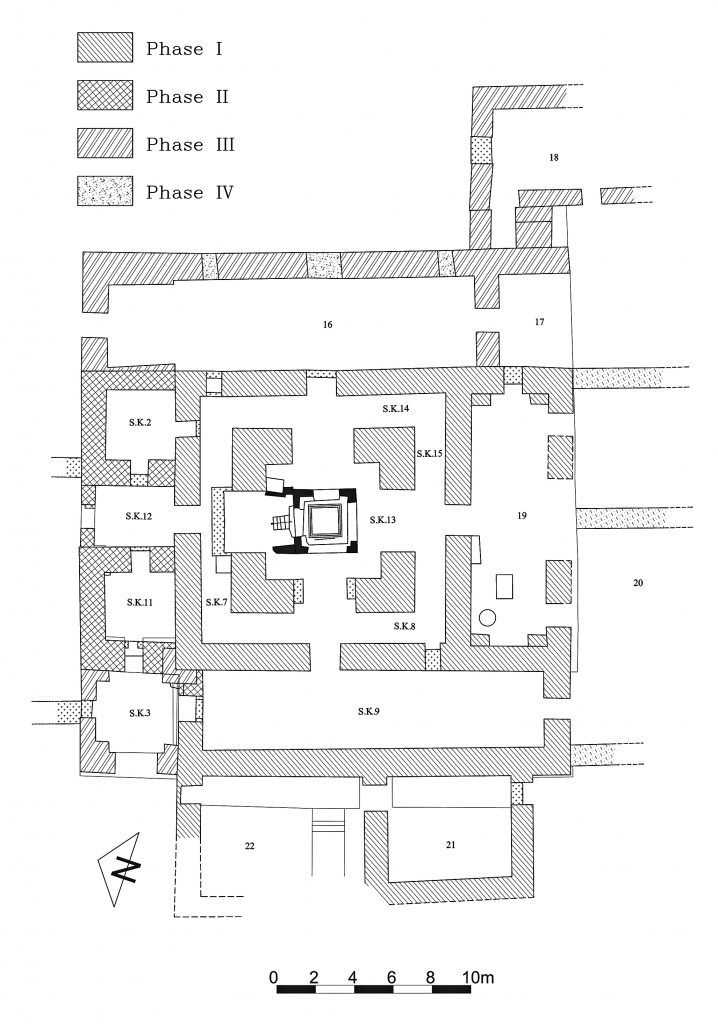

Discovery of a ‘chahar-taq’ in 1978 was totally unexpected, and forced re-assessment of the overall Zardeh tableland and its archaeological history. The site has been labeled Gach Dāwar (“Dawar’s Gypsum”), in honourofthe land owner who graciously allowed stones cleared from his fields to be use in building the Canadian expedition house. A chahar-taq is a distinctively shaped dome-chamber where a sanctuary dome is carried by four L-shaped piers.

There are arched openings on each of a chahar-taq’s four sides. When this architectural form was first employed in Sasanian times, it was exclusively linked with operation of a Zoroastrianism fire-temple. The Parthians were not Zoroastrian; there are no domed fire-temples in Parthian times. The chahar-taq, then, speaks incontrovertibly of a Sasanian monument; and, Zoroastrianism was the state religion of Sasanian Iran. Therefore, the chahar-taq of the Zardeh tableland is best seen as an official statement by the new third century Sasanian regime that the maverick days of the Parthian warlord were over.

Further examination made by the Iranian Heritage Organization in 2008 exposed the heart of the temple, revealing a central platform that served as the podium for a fire-altar. The podium’s four corner piers would logically have been the supports to carry a protective canopy over the sacred fire. But, while there is clear evidence that the chahar taq functioned as a fire-temple well into Islamic times, no fire altars have ever been recovered. Other rooms on the periphery of the complex can be easily interpreted as proving appropriate spaces for unspecified liturgical or community uses. A definitive date of the mid-980s CE for the continuing functioning of the complex as a fire-temple is provided by Būyid era coins found beneath collapsed masonry that marks the final demise of the fire-temple role of the complex.

The ancillary side-rooms of the chahar-taq, although originally constructed in the Sasanian era, were re-used in Islamic times for activity that is reflected in the unearthing of many glass vessel fragments found in very ashy contexts. Whether the activity that they represent was originally connected with operation of the fire-temple has not been determined. But no appropriate artifacts, such as wasters or slag, were found to substantiate the theory that these spaces were used as workshops for glass making. The side rooms likely continued in use beyond the time when the fire-temple was functioning, possibly as late as Seljuq times.

Before this activity started, large pits were dug through the floors of each of the ancillary rooms on the northwestern side of the complex, including the unearthing of what was most likely a treasure pot.

For further reading see:

re: Decorative stuccoes, see Architectural Decoration page